Pelvic congestion syndrome: does one name fit all?

Pier Luigi ANTIGNANI2;

Lorenzo TESSARI1

2 Director, Vascular center, Nuova Villa

Claudia, Rome, Italy

Abstract

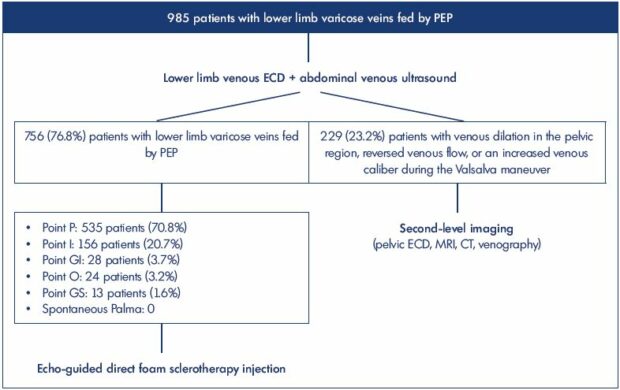

The pelvic congestion syndrome definition includes two not so frequently overlapping scenarios: (i) pelvic venous engorgement with lower abdomen symptomatology; and (ii) lower limb varicose veins fed by pelvic escape points that are generally less prone to develop the abdominal clinical manifestation typical for pelvic congestion syndrome. We retrospectively evaluated 985 female patients (43±11 years old; 23±5kg/m2 BMI) who visited our offices for lower limb varicose veins of pelvic origin. Second-level imaging was needed for 229 patients. The remaining 756 patients underwent direct echo-guided foam sclerotherapy in proximity of the pelvic escape points. At a mean follow-up of 4.1±1.4 years, 595 patients were successfully treated. Among the successfully treated group, mild lower abdomen heaviness and occasional dyspareunia was reported by 14 and 11 women, respectively, prior to the injection. At the end of the follow up, a significant reduction in the symptomatology was reported for both lower abdomen heaviness and dyspareunia. In traditional pelvic congestion syndrome, an accurate diagnosis protocol eventually ends in an interventional radiology suite. Conversely, in cases of lower limb varicose veins of pelvic origin, the phlebologist can, and in our opinion should, assume a pivotal role both in the diagnostic and therapeutic part.

Introduction

As is the case for lower limb symptoms in chronic venous disease (CVD), venous reflux is considered responsible for the clinical presentation of the potentially debilitating pelvic congestion syndrome (PCS), ie, dull aching pain in the lower abdomen, dyspareunia, abdominal and/or pelvic tenderness, dysmenorrhea, lumbosacral neuropathy, urinary frequency, and rectal discomfort.1 A diagnosis of PCS is usually made after the involvement of several specialists and the exclusion of other pelvic pathologies. Nevertheless, diagnosis and treatment of this disease can become challenging due to multiple and sometimes side crossing interconnections among the ovarian, internal iliac, and femoral veins.2 Patients with PCS can present with varices of the upper posteromedial thigh, together with varicose veins of the buttocks, perineal, and labial regions. Connections with the great saphenous vein can also feed reflux not involving the saphenofemoral junction, thereby leading an inexperienced sonographer to an incorrect interpretation and therapeutic indication.

The veins of the pelvis are connected with the lower limb venous system via pudendal, sciatic, gluteal, and perforating veins.3 Leaking points of the pelvis can feed several patterns of lower limb venous reflux. The denomination of such reflux patterns depends on the anatomical site in which the reflux occurs. (Figure 1).4 The perineal point is located on the perineal membrane where the perineal veins proceed after having received the labial tributaries, thereby connecting the internal and external pudendal systems. The inguinal point is found on the superficial inguinal ring where the veins of the round ligament interconnect with the superficial veins of the anterior abdominal wall and with the vein of the Nuck diverticulum. The obturator point is found inside the obturator canal, and it connects the deep veins of the medial thigh muscles with the internal iliac vein. The superior and inferior gluteal points are found in the gluteal region in association with the sciatic vein and the inferior gluteal veins, respectively.

All pelvic escape points represent leaking points that can actually reduce the venous hypertension of the pelvic region, transferring this overload to the varicose veins of the lower limbs. For this reason, according to our opinion and daily clinical practice, a deeper analysis of PCS is needed. Until now, the PCS definition includes two not so frequently overlapping scenarios: (i) pelvic venous engorgement with lower abdomen symptomatology; and (ii) lower limb varicose veins fed by pelvic escape points that are generally less prone to develop the abdominal clinical manifestation typical for PCS.

In almost 40% of cases, the ovarian and/or internal iliac venous plexus reflux does not extend into the varicose veins of the lower limbs.5,6 In traditional PCS, the role of the phlebologist is mainly to manage the clinical symptoms and develop a diagnosis protocol that will be carried out by a different specialist. Conversely, in cases of lower limb varicose veins of pelvic origin, the phlebologist can, and in our opinion should, assume a pivotal role both in the diagnostic and therapeutic part.

Figure 1. Study population and diagnostic flow chart.

Abbreviations: CT, computed tomography; ECD, echo color Doppler; GI, inferior gluteal point; GS, superior gluteal point; I, inguinal

point; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; O, obturator point; P, perineal point; PEP, pelvic escape point.

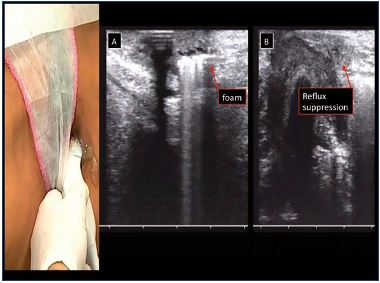

As such, we in our personal experience (not yet published) retrospectively evaluated 985 female patients (43±11 years old; 23±5kg/m2 BMI) who visited our offices for lower limb varicose veins of pelvic origin. All the patients underwent an abdominal and a lower limb echo color Doppler (ECD) venous scanning of the lower limbs and the perineal region. Refluxes were evoked both by Valsalva and compression/relaxation maneuvers (Figure 2). The patients were scanned while standing to avoid false negative outcomes. The patient underwent second level diagnostics (pelvic ultrasound, MRI, CT, and venography) when there was an anamnestic suspect, venous dilation in the pelvic region, reversed venous flow, or an increased venous caliber during the Valsalva maneuver. Alternatively, echo-guided foam sclerotherapy injections were directly performed in the proximity of the pelvic escape points. The specific anatomic location of the leaking points are reported together with the diagnostic flow-chart in Figure 1.

Second-level imaging was done in 229 patients, whereas the remaining 756 patients underwent direct echo-guided foam sclerotherapy in the proximity of the pelvic escape points (Figure 3). All treated patients underwent lower limb and abdominal ECD scanning in the standing position annually after the first injection. At a mean follow-up of 4.1±1.4 years, 595 patients were successfully treated. Reflux was suppressed after 1 injection in 304 patients, 2 injections in 281 patients, and 3 injections in 10 patients (Figure 4). Among the successfully treated group, mild lower abdomen heaviness and occasional dyspareunia was reported by 14 and 11 patients, respectively, prior to the injection. At the end of the follow-up, a significant reduction in the symptomatology was reported for both lower abdomen heaviness and dyspareunia.

Figure 3. Direct foam sclerotherapy injection and sonographic

visualization of the treated venous plexus.

Figure 4.

A. Appearance of hyperechogenic foam after direct foam

sclerotherapy injection.

B. Pelvic reflux suppression.

Conclusions

The associated symptomatology with PCS can become extremely debilitating due to chronic lower abdomen pain, dyspareunia, dysmenorrhea, swollen vulva, lumbosacral neuropathy, and urinary urgency.1-7 An accurate diagnostic protocol requires the involvement of different specialists and diagnostic techniques. Until now, the role of the phlebologist seems to be extremely marginal in this condition, being mainly limited to the assessment and eventual treatment of the associated lower limb varicosities. Nevertheless, in addition to the ovarian and pelvic plexus engorgement, the PCS definition also includes lower limb varicose veins fed by pelvic escape points. According to our opinion and clinical experience, a clear distinction should be made between PCS and lower limb chronic venous disease of pelvic origin. An anatomical and pathophysiological link exists between the two conditions, but two distinct clinical scenarios characterize these different venous impairments.

On one hand, incompetence of an ovarian/pelvic plexus leads to an engorgement of the lower abdomen drainage system; therefore, leading to the typical symptoms. On the other hand, pelvic escape points feed the reflux that leads to lower limb varicose veins. In an apparent paradox, the leaking points that are feeding the lower limb varices become an escape point for the venous hypertension inside the abdomen. This interpretation provides a possible explanation of the extremely mild pelvic symptomatology in patients affected by varices fed by pelvic escape points. The same reason could explain the increased chronic pelvic pain of PCS patients in cases of lower abdominal venous congestion erroneously treated by ablation of those lower limb varicose veins that were decongesting the pelvic plexus. Moreover, unsatisfactory outcomes of traditional PCS treatments could be related to an incomplete diagnostic work-up.8

On this basis, we suggest a careful and consistent evaluation of these different venous impairments, separating the scenario of PCS from the one of Chronic pelvic Venous Disease (CpVD). It is important to pay extreme attention during both the detailed anamnestic interview and the sonographic scanning.

REFERENCES

1. Durham JD, Machan L. Pelvic congestion syndrome. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2013;30:372-380.

2. Meissner MH. Lower extremity venous anatomy. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2005;22:147-156.

3. Kachlik D, Pechacek V, Musil V, Baca V. The venous system of the pelvis: new nomenclature. Phlebology. 2010;25:162-173.

4. Franceschi C, Zamboni P. Principles of Venous Hemodynamics. New York, NY: Nova Biomedical Books; 2009.

5. Asciutto G, Asciutto KC, Mumme A, Geier B. Pelvic venous incompetence: reflux patterns and treatment results. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2009;38:381- 386.

6. Jin KN, Lee W, Jae HJ, Yin YH, Chung JW, Park JH. Venous reflux from the pelvis and vulvoperineal region as a possible cause of lower extremity varicose veins: diagnosis with computed tomographic and ultrasonographic findings. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2009;33:763-769.

7. Stones RW, Mountfield J. Interventions for treating chronic pelvic pain in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000:CD000387.

8. Smith PC. The outcome of treatment for pelvic congestion syndrome. Phlebology. 2012;27:74-77.