Role of compression therapy in lipedema

Isabel Forner-Cordero, MD, PhD, Associate Professor

Lymphedema Unit, Rehabilitation Department, Hospital Universitari i Politècnic La Fe, University of Valencia, Valencia, Spain

Juan Vazquez-Diez, MD

Lymphedema Unit, Rehabilitation Department, Hospital General Universitari de Castelló, Castellón de La Plana, Spain

ABSTRACT

Lipedema is a very frequent chronic disease, frequently underdiagnosed and misdiagnosed and whose pathophysiology is still under research. Patients, most of them women, present with evident disproportion in the distribution of fat between the upper and lower part of the body, swelling, easy bruising, and pain in the lower limbs, and sometimes in the upper limbs.

The major aims of its management are to reduce symptoms such as heaviness and pain, reshape the affected limbs, control weight, improve mobility, and improve the quality of life. Setting realistic expectations is important for both patient and medical care providers. Depending on the stage, treatment includes physical therapies, compression garments, exercise, diet, psychological support, and surgical treatment in selected cases. The approach must be integrative and multidisciplinary, looking for a change in patients’ habits.

Although there is no scientific evidence to support the additional value of using compression garments for managing lipedema, some reports do show benefits in reducing pain in lipedema patients. Clinical guidelines and consensus documents state that compression therapy should be part of the conservative treatment for lipedema, and that patients with lipedema should receive compression garments as part of their treatment. The lowest compression class that alleviates the patient’s symptoms should be preferred. Further research is needed.

What is lipedema?

Lipedema is a chronic disease that affects many women worldwide, causing swelling and abnormal fat deposition in the lower limbs, bruising, and pain.1 There is an evident disproportion in the distribution of fat in the lower limbs and sometimes the upper limbs.2 Due to the lack of awareness and knowledge among professionals, the real prevalence is underestimated due to misdiagnosis or failure to refer patients.3-5 Etiopathogenic mechanisms have not yet been fully described; however, lipedema has been associated with lymphatic dysfunction, genetic background, and susceptibility to influence by hormonal changes.6 The main complaint of the patients is the enlargement of the lower limbs, with pain or discomfort. As the disease progresses, leg heaviness may increase and cause impairments in mobility7 and global capacity. Lipedema, even in early stages, has been associated with several health problems and a lower quality of life.8

Despite the increase in studies on lipedema and greater awareness among health care professionals, its recognition as a disease is recent. In 2018, following the request of the European Society of Lymphology, it was included in the International Classification of Diseases (ICD11) by the World Health Organization as EF02 noninflammatory alteration of subcutaneous fat.9 It is necessary to promote knowledge of this disease to help patients obtain an early diagnosis and appropriate management.

Pathophysiology

The etiology of lipedema is still under research, and various hypotheses have been suggested.10 These include genetic predisposition,11,12 with the epigenetic influence of hormonal changes, particularly estrogens, fat gain, and inflammation, leading to a dysfunction in adipocyte cells and differentiation13,14 and microvascular dysfunction in lymphatic and blood vessels.15

The subcutaneous adipose tissue of lipedema is characterized by an increase in the quantity and structure of fat, which is resistant to weight loss and is therefore considered persistent fat.16,17 Pathological studies show an increase in adipose tissue due to adipocyte hyperplasia or hypertrophy and cell death due to hypoxia,18 capillary filtration that could overload a morphologically normal lymphatic system, and capillary fragility that can cause easy bruising.2

There is increasing evidence of the presence of a chronic low-grade inflammatory state that contributes to the development of obesity-related disorders, particularly metabolic dysfunction.19,20

The dysregulated expression of inflammatory factors, caused by excess adiposity and adipocyte dysfunction, has been linked to the pathogenesis of various pathological processes through altered immune responses. New factors secreted by adipose tissue have been identified that promote inflammatory responses and metabolic dysfunction or contribute to the resolution of inflammation and have obesity-related effects.21,22 Inflammatory cytokines or adipokines could affect the phenotypic presentation of lipedema or cause disorders that can be confused with lipedema.

Clinical manifestations of lipedema

The patients present a symmetrical and abnormal increase in adipose tissue from the hips, including buttocks, thighs, and calves (for calves, only in lipedema type 3) (Figures 1A, 2A, and 3A). Furthermore, they always present bilateral involvement of the legs, sparing the foot, causing the typical “cuffing sign” only in lipedema type 3, which is the abrupt end of the accumulation of fatty deposits that can appear in both the ankles and wrists (Figure 2A). 23 There is an evident disproportion in the distribution of fat in these patients.24 The presence of symptoms such as pain, heaviness, or discomfort in the legs is necessary for the diagnosis of lipedema.25,26 Its absence in a patient with increased fat would indicate lipohypertrophy, not lipedema. It can also affect upper limbs.23

Patients report worsening leg edema throughout the day due to standing and heat. Furthermore, they report greater sensitivity to pain and the appearance of bruises, spontaneously or from light trauma (Figure 2A). 23

On the other hand, it has been described that in patients with lipedema, the prevalence of joint hypermobility is much higher than in the general population, which may suggest that it is a comorbidity and may be related to a collagenopathy involved in its condition.27

According to a previous study from our group, the differential diagnosis between lipedema and lymphedema can be made by evaluating the presence of three clinical features: bruising, disproportion between the upper and lower part of the body, and spared feet.28

Progression of lipedema, described as a change in volume superior to 10%, was related to global fat increase.29

Figure 1. Case 1: 25-year-old patient with type 3 lipedema, stage 1, (A) presenting with easy bruising, pain, and swelling in lower limbs; (B) wearing a footless legging in circular fabric ccl2.

Figure 2. Case 2: 38-year-old patient with type 3 lipedema. (A) Front view and side view. (B) Front view and side view of flat-knit pantyhose worn by the patient.

Figure 3. Case 3: 48-year-old patient with type 2 lipedema (A) affecting hips to knees, sparing the lower part of the legs. (B) Side view of Bermuda pantyhose worn by the patient.

Complementary tests

A blood test with a complete blood count and biochemistry is recommended, with a study of thyroid hormones to rule out systemic causes of edema and to detect comorbidities that may appear.

Imaging tests such as lymphoscintigraphy, lymphofluoroscopy, magnetic resonance lymphography, and high-resolution Doppler ultrasound can provide structural and functional information about the lymphatic system, but do not show any pathognomonic signs of lipedema that could help us with the definitive diagnosis.30,31

The lack of a pathognomonic test for lipedema makes it impossible to have a certain diagnosis.

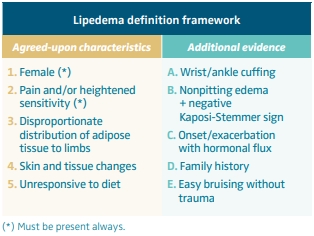

Lipedema definition framework

Through analysis of the literature and consensus among the authors, a definition framework for lipedema was reached based on clinical manifestations (Table I). 32 According to a recently proposed framework for research in lipedema, a patient should be eligible for studies if she is female, has pain and/or heightened sensitivity and one of the following:

1. All five agreed-upon characteristics are present.

2. Two more agreed-upon characteristics and at least two characteristics from the additional evidence column are present.

3. One more agreed-upon characteristics and at least four characteristics from the additional evidence column are present.

Table I. Lipedema definition framework. Based on reference 32: Keith et al. Lymphat Res Biol. 2024;22(2):93-105.

Classification

Based on inspection and palpation, lipedema can be classified in 4 clinical stages of severity.3-5

Stage 1: the skin surface is normal, and the subcutaneous fatty tissue has a soft consistency with multiple small nodules.

Stage 2: the skin surface becomes uneven and harder due to the increasing nodular structure (big nodules) of the subcutaneous fatty tissue (liposclerosis).

Stage 3: lobular deformation of the skin surface due to increased adipose tissue. The nodules vary in size and can be distinguished from the surrounding tissue on palpation. The phenomenon of “peau d’orange” can be seen by pressing the skin.

Stage 4: lipolymphedema.

Management of lipedema

Effective management of lipedema, ideally coordinated through a specialized Lymphedema Unit, is associated with improved pain control, limb contour, mobility, and overall quality of life.5 A multidisciplinary, patient-centered approach is essential, integrating psychosocial support, self-care education, dietary interventions, physical activity, and, where appropriate, surgical options.

Psychosocial and educational support

Educational interventions are critical to empower patients in long-term disease management. These include counseling on genetic factors, pregnancy, and weight control, as well as daily guidance on compression therapy, skin care, and pain management. Setting realistic, personalized goals fosters adherence and improves psychological outcomes.5

Diet and weight management

Dietary interventions should focus on sustainable weight control rather than rapid loss, which may lead to psychological distress and subsequent weight gain. To date, no diets have clearly demonstrated efficacy in lipedema. Diets showing promise include the Harvie and Howell diet,33 ketogenic diet,34-37 Rare Adipose Disorders diet,38 anti-inflammatory and Mediterranean-based regimens,39 with emerging evidence supporting their role in symptom relief and inflammation reduction. Most of them are still under investigation. Reducing carbohydrate intake and increasing the interval of fasting could also improve edema, inflammation, and fibrosis.

Physical activity

Physical exercise, though historically undervalued in lipedema care, offers notable benefits including improved lymphatic flow, reduced edema, and enhanced mobility.4,5,40,41 Low-impact aerobic activities, particularly aquatic exercise and strength training, are well-tolerated and effective. High-intensity regimens should be avoided due to the risk of exacerbating pain and bruising. Various types of exercise, such as aquatic exercises and strength training, have been shown to alleviate symptoms and improve the quality of life of patients with lipedema.42 However, standardized guidelines for prescription are lacking, highlighting the need for recommendations and further research.

Pharmacological treatment

Although various pharmacologic agents (eg, corticosteroids, diuretics, flavonoids) have been proposed, there is currently insufficient evidence to support their routine use in lipedema management.43 Ongoing research is evaluating their potential in modulating inflammation and edema.

Lymphedema decongestive therapy

Manual lymphatic drainage and compression therapies may alleviate discomfort and enhance quality of life2,44 but are not proven to significantly reduce volume or prevent progression in pure lipedema cases.45 These therapies are generally not considered first-line treatment but can help in relieving pain by the means of modulation of C nerve fibers.

Surgical interventions

Bariatric surgery may be considered in patients with significant obesity (body mass index [BMI] >40, or >35 with comorbidities), though its effect on limb volume is limited. Liposuction, particularly power-assisted (PAL) and water-assisted (WAL) techniques, has emerged as a key option for patients with refractory symptoms and functional impairment.46 Surgical planning must prioritize lymphatic preservation and is ideally pursued following weight optimization. After liposuction, subsequent surgeries to remove excess skin or provide thigh lifting, as well as laser lipolysis may be needed. However, despite surgery, the use of continuous compression will remain essential. A recent study reported a lower use of compression after liposuction without relapse.47

Role of compression in lipedema

How does compression work?

Compression therapy primarily exerts its effects by increasing tissue pressure, thereby counteracting capillary leakage—an essential mechanism in the prevention and management of edema. In addition to reducing capillary permeability, it enhances lymphatic absorption through the opening of anchoring filaments in lymphatic capillaries, facilitating the entry of interstitial fluid into the lymphatic system.48 In cases where lymphatic capillaries exhibit reduced absorptive capacity or impaired lymph transport, compression therapy assists in directing interstitial fluid proximally or into subfascial pathways to promote adequate drainage and reabsorption.49

Compression also modulates cutaneous microcirculation, normalizing its function by increasing leukocyte adhesion and improving vasomotor activity, which collectively enhance skin nutrition.50 Another significant effect is the elevation of tissue oxygen partial pressure, often diminished in advanced chronic venous insufficiency. This is achieved through the breakdown of fibrosclerotic tissue characteristic of advanced stages of venous disease and lymphedema, as well as through the downregulation of proinflammatory cytokines and growth factor receptors.45

Within the lymphatic system, compression induces a rise in skin temperature, which leads to the opening of intercellular junctions between lymphatic endothelial cells and, consequently, an increase in fluid reabsorption. Additionally, it exerts a prolymphokinetic effect by stimulating the myocontractile activity of lymphangions.51,52

Available evidence

What do studies say about compression? The few existing studies suggest that compression is beneficial in lipedema patients.

A recently published pilot study with 29 patients with lipedema demonstrated that wearing circular fabric micromassage leggings for 3 hours a day while exercising helped reduce lower-limb volume and pain.53

The Spanish National Health Service does not cover compression garments for lipedema owing to the lack of evidence regarding their effectiveness. As a result, the Health Technology Agency conducted a systematic review to assess the safety and efficacy of these garments for the treatment of lipedema. Studies published up to April 2024 in various medical databases were reviewed, evaluating the efficacy and safety of compression garments for people with lipedema when used in conjunction with usual treatment (exercise and dietary measures) versus usual treatment alone. No scientific evidence was found to support the additional value of using compression garments in combination with usual treatment for managing lipedema.54

Research in this field has many limitations:

• No definitive diagnostic test for lipedema.

• Few studies.

• Few randomized clinical trials.

• Studies with multimodal therapies.

• Small sample sizes, pilot studies.

• Surveys with subjective outcome measures.

• Adherence to wearing of compression garments not objectively measured.

However, clinical guidelines state that the use of compression aims to reduce symptoms (pain and heaviness), edema, and optimize the contours of the limbs. 1 A recent meta-analysis reported the beneficial effect of compression in the reduction of pain.55

Compression can be administered through bandages, self-adjusting devices, or compression garments.40 In cases of edema with pitting, it is essential to use multicomponent bandages before prescribing compression garments in the maintenance phase.30

Despite limited research, several clinical guidelines and consensus documents establish that compression therapy should be part of the conservative treatment for lipedema, and that patients with lipedema should receive compression garments as part of their treatment.30,40

Expected effects when using compression in lipedema

Since fat tissue cannot be reduced through compression, compression garments are primarily aimed at improving symptoms, reducing pain and heaviness.3,5 It is known that they have an anti-inflammatory and oxygenating effect on tissues. Moreover, they can prevent fluid accumulation and the potential progression to lymphatic insufficiency. Patients should be informed that compression is not suitable for reducing adipose tissue.45

Recommendations

Currently, there are no guidelines for prescribing compression garments in lipedema.56 No research studies are available on the type of stockings or the level of compression, so the prescription provided by the physician is essentially empirical. In our experience, a phlebologist is more likely to prescribe circular fabric garments, whereas a lymphologist will probably indicate flat-knit garments.

Compression needs vary depending on the patient’s clinical manifestations, pain, and physical ability to don and doff compression garments or bandages; therefore, we recommend involving the patient, physician, therapist, and provider in this process to maximize adherence to compression therapy and effectiveness.

Type of fabric

When choosing and prescribing compression garments, the most suitable fabric should be considered individually, in addition to the required pressure, as the effect of compression treatment depends both on the pressure and the characteristics of the fabric. Compression garment types can be combined to cover the limbs affected by lipedema. Fabrics vary from lightweight and micromassage materials to circular and flat-knit fabrics, with the latter providing the strongest containment.

In some cases, multicomponent low-elasticity compression bandages or velcro devices may be required to reduce edema.30

Compression class

The rigidity of the garments or the compression class level is determined independently of the fabric type and based on the stage of lipedema. If pain increases with compression, the compression class can be reduced, or garments can be layered on top of each other. A higher compression class does not necessarily result in better outcomes. Furthermore, the lowest compression class that alleviates the patient’s symptoms should be preferred.40

Compression in mild stages

In the milder stages of lipedema, it is recommended to prescribe standard circular fabric pantyhose with compression class 2 (ccL 2) for daytime and daily use, with which patients usually report immediate benefits in reducing edema and heaviness sensation. Since pantyhose are not easy to tolerate and lipedema spares the feet, leggings can be a good alternative as long as the feet do not become edematous (Figure 1B).

Impact of compression hosiery

Despite a high nonadherence rate of 34% among compression hosiery users57 and 30% in lipedema patients specifically,58 compression garments have a good impact on lipedema symptoms control.

The top 3 reasons reported for wearing compression garments were to feel supported (73%), for reduction in pain (67%), and for improvement in mobility (54%), according to a survey.53

On the other hand, the main complaints about wearing compression garments included the following: doff-and-donning (77.7%), too warm (72.1%), ugly (65.9%), popliteal pain (62.8%), discomfort (62.7%), bad personal image (45.3%), itchy (42.3%), irritations (37.9%), bad fitting (32.9%), bad toleration to compression (13.7%). Patients with a higher BMI complained more of doff-and-donning, discomfort, and bad toleration to compression than patients with a lower BMI.59

The patients felt that they had not been fully informed by the prescriptor, and practical information should be given to the patient about correct fitting, wear duration, and washing of the garment, as well as what aids they should buy.60

Doff-and-donning difficulty can reduce adherence to wearing of compression garments and limit the independence of the patient.

Case 1

A 25-year-old woman with lipedema type 3, in stage 1, presented easy bruising, pain, and swelling in her lower limbs since the age of 15 (Figure 1A). We prescribed a footless legging in circular fabric ccl2 (Figure 1B), which proved enough to improve her symptoms and was well tolerated during summer, as she was able to wear sandals.

Case 2

We present a 32-year-old woman complaining of lower-limb swelling since puberty. She was diagnosed with lymphedema and obesity and was referred to the Lymphedema Unit of our center. Whereas her BMI was 30.9, her waist-to-height ratio fell into the healthy range (0.46). She had already tried circular fabric compression garments, but the wrinkles on the popliteal fossa made them uncomfortable to wear. The prescription of flat-knitted pantyhose significantly improved fitting, as shown in Figure 2B.

Case 3

This 48-year-old patient has type 2 lipedema (affects hips to knees, sparing the lower part of the legs) (Figure 3). The differential diagnosis with lipohypertrophy must be done: lipedema presents pain and discomfort whereas lipohypertrophy does not. In this case, due to the limb deformity, achieving an adequate fit with circular-knit garments is challenging; therefore, flat-knit compression is recommended. As legs are unaffected and the garment must cover the affected body areas, a Bermuda pantyhose was prescribed. The patient reported satisfaction with the hosiery and exhibited improved adherence (Figure 3B).

Conclusions

The use of compression in the management of lipedema should be recommended in all the patients, regardless of the conservative or surgical approach. The selection of fabric, class, and type of hosiery should be tailored to the individual’s specific characteristics, with an emphasis on symptom alleviation.

CORRESPONDING AUTHOR

Isabel Forner-Cordero, MD, PhD

Avinguda de Fernando Abril Martorell, nº106. 46026 Valencia, Spain

e-mail: ifornercordero@gmail.com

References

1. Foldi E, Foldi M. Lipedema. In: Foldi’s Textbook of Lymphology. Elsevier GmbH; 2006:417-427.

2. Fife CE, Maus EA, Carter MJ. Lipedema: a frequently misdiagnosed and misunderstood fatty deposition syndrome. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2010;23(2):81-92.

3. Lontok E. Lipedema: A Giving Smarter Guide. Milken Institute Strategic Philanthropy; 2017.

4. Dayan E, Kim J, Smith M, et al. Lipedema – The Disease They Call FAT: An Overview for Clinicians. Lipedema Simplified LLC; 2017.

5. Wounds UK. Best Practice Guidelines: The Management of Lipoedema. Wounds UK; 2017.

6. Forner-Cordero I, Forner-Cordero A, Szolnoky G. Update in the management of lipedema. Int Angiol. 2021; 40(4):345-357.

7. Falck J, Rolander B, Nygårdh A, Jonasson LL, Mårtensson J. Women with lipoedema: a national survey on their health, health-related quality of life, and sense of coherence. BMC Womens Health. 2022;22(1):457.

8. Dudek JE, Białaszek W, Gabriel M. Quality of life, its factors, and sociodemographic characteristics of Polish women with lipedema. BMC Womens Health. 2021;21(1):27.

9. World Health Organization. [Internet]. International classification of diseases for mortality and morbidity statistics (11th Revision). Published 2019. Accessed February 2, 2025. https://icd.who.int/en/

10. Szél E, Kemény L, Groma G, Szolnoky G. Pathophysiological dilemmas of lipedema. Med Hypotheses. 2014;83(5):599-606.

11. Paolacci S, Precone V, Acquaviva F, et al; GeneOb Project. Genetics of lipedema: new perspectives on genetic research and molecular diagnoses. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2019;23(13):5581-5594.

12. Klimentidis YC, Chen Z, Gonzalez-Garay ML, et al. Genome-wide association study of a lipedema phenotype among women in the UK Biobank identifies multiple genetic risk factors. Eur J Hum Genet. 2023;31(3):338- 344.

13. Al-Ghadban S, Diaz ZT, Singer HJ, Mert KB, Bunnell BA. Increase in leptin and PPAR-γ gene expression in lipedema adipocytes differentiated in vitro from adipose-derived stem cells. Cells. 2020;9(2):430.

14. Kruppa P, Gohlke S, Łapiński K, et al. Lipedema stage affects adipocyte hypertrophy, subcutaneous adipose tissue inflammation and interstitial fibrosis. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1223264.

15. Kruppa P, Georgiou I, Biermann N, Prantl L, Klein-Weigel P, Ghods M. Lipedema-pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment options. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2020;117:396- 340.

16. Herbst KL. Feingold K, Ahmed S, et al, eds. Subcutaneous Adipose Tissue Diseases: Dercum Disease, Lipedema, Familial Multiple Lipomatosis, and Madelung Disease. Endotext [Internet]. MDText; 2019. Accessed April 14, 2025. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/ NBK278943/

17. Bel Lassen P, Charlotte F, Liu Y, et al. The FAT Score, a fibrosis score of adipose tissue: predicting weight-loss outcome after gastric bypass. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102(7):2443-2453.

18. Suga H, Eto H, Aoi N, et al. Adipose tissue remodeling under ischemia: death of adipocytes and activation of stem/ progenitor cells. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;126(6):1911-1923.

19. Hotamisligil GS. Inflammation and metabolic disorders. Nature. 2006;444(7121): 860-867.

20. Ouchi N, Kihara S, Funahashi T, Matsuzawa Y, Walsh K. Obesity, adiponectin and vascular inflammatory disease. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2003;14(6):561-566.

21. Takaoka M, Nagata D, Kihara S, et al. Periadventitial adipose tissue plays a critical role in vascular remodeling. Circ Res. 2009;105(9):906-911.

22. Monteiro R, Azevedo I. Chronic inflammation in obesity and the metabolic syndrome. Mediators Inflamm. 2010;2010:289645.

23. Forner-Cordero I, Perez-Pomares MV, Forner A, Ponce-Garrido AB, Munoz-Langa J. Prevalence of clinical manifestations and orthopedic alterations in patients with lipedema: a prospective cohort study. Lymphology. 2021;54(4):170-181.

24. Van Geest AJ, Esten SC, Cambier JP, et al. Lymphatic disturbances in lipoedema. Phlebologie. 2003;32:138-142.

25. Fries R. Ursachensuche bei generalisierten und lokalisierten odemen. [Differential diagnosis of leg edema]. MMW Fortschr Med. 2004;146:39-41.

26. Herpertz U. Der missbrauch des lipödems. [The misuse of lipedema]. Lymphol Forsch Prax. 2003;7:90-93.

27. Herbst KL, Mirkovskaya L, Bharhagava A, Chava Y, Te CHT. Lipedema fat and signs and symptoms of illness, increase with advancing stage. Arch Med. 2015;7(4):1-8.

28. Forner-Cordero I, Muñoz-Langa J, Morilla-Bellido L. Building evidence for diagnosis of lipedema: using a classification and regression tree (CART) algorithm to differentiate lipedema from lymphedema patients. Int Angiol. 2025;44(1):71-79.

29. Forner-Cordero I, Muñoz-Langa J. Is lipedema a progressive disease? Vasc Med. 2025;30(2):205-212.

30. Kruppa P, Georgiou I, Biermann N, Prantl L, Klein-Weigel P, Ghods M. Lipedema-pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment options. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2020;117: 396-403.

31. Hirsch T, Schleinitz J, Marshall M, Faerber G. Can high-resolution ultrasound be used for the differential diagnosis of lipoedema? Phlebologie. 2018;47:182- 187.

32. Keith L, Seo C, Wahi M, et al. Proposed framework for research case definitions of lipedema. Lymphat Res Biol. 2024;22(2):93-105.

33. Harvie M, Howell T. The 2-Day Diet: The Quick & Easy Edition. Vermilion; 2014.

34. Cannataro R, Michelini S, Ricolfi L, et al. Management of lipedema with ketogenic diet: 22-month follow-up. Life (Basel). 2021;11(12):1402.

35. Herbst KL, Kahn LA, Iker E, et al. Standard of care for lipedema in the United States. Phlebology. 2021;36(10):779-796.

36. Lundanes J, Sandnes F, Gjeilo KH, et al. Effect of a low-carbohydrate diet on pain and quality of life in female patients with lipedema: a randomized controlled trial. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2024;32(6):1071-1082.

37. Verde L, Camajani E, Annunziata G, et al. Ketogenic diet: a nutritional therapeutic tool for lipedema? Curr Obes Rep. 2023;12(4):529-543.

38. Herbst KL. Rare adipose disorders (RADs) masquerading as obesity. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2012;33:155-172.

39. Di Renzo L, Cinelli G, Romano L, et al. Potential effects of a modified Mediterranean diet on body composition in lipoedema. Nutrients. 2021;13(2):358.

40. Shin BW, Sim YJ, Jeong HJ, Kim GC. Lipedema, a rare disease. Ann Rehabil Med. 2011;35(6):922-927.

41. Okhovat JP, Alavi A. Lipedema: a review of the literature. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2015;14(3):262-267.

42. Annunziata G, Paoli A, Manzi V, et al. The role of physical exercise as a therapeutic tool to improve lipedema: a consensus statement from the Italian Society of Motor and Sports Sciences (Società Italiana di Scienze Motorie e Sportive, SISMeS) and the Italian Society of Phlebology (Società Italiana di Flebologia, SIF). Curr Obes Rep. 2024;13(4):667-679.

43. Bonetti G, Herbst KL, Dhuli K, et al. Dietary supplements for lipedema. J Prev Med Hyg. 2022;63(2 Suppl 3): E169-E173.

44. Szolnoky G, Borsos B, Barsony K, Balogh M, Kemeny L. Complete decongestive physiotherapy of lipedema with or without pneumatic compression: a pilot study. Lymphology. 2008;41:50-52.

45. Faerber G, Cornely M, Daubert C, et al. S2k guideline lipedema. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2024;22(9):1303-1315.

46. Warren AG, Janz BA, Borud LJ, Slavin SA. Evaluation and management of the fat leg syndrome. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;119: 9e-15e.

47. Bejar-Chapa M, Rossi N, King N, Hussey MR, Winograd JM, Guastaldi FPS. Liposuction as a treatment for lipedema: a scoping review. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2024;12(7):e5952.

48. Partsch H. Understanding the pathophysiological effects of compression. In: European Wound Management Association Understanding Compression Therapy. Medical Education Partnership Ltd; 2003:2-4.

49. Downie SP, Raynor SM, Firmin DN, et al. Effects of elastic compression stockings on wall shear stress in deep and superficial veins of the calf. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;294(5):H2112-H2120.

50. Cavezzi A, Colucci R, Barsotti N, di Ionna G, Piergentili M. Compression therapy and the autonomic nervous system. In: Mosti G, Partsch H, eds. Compression Therapy. Edizioni Minerva Medica; 2022:34-44.

51. Herouy Y, Kahle B, Idzko M, et al. Tight junctions and compression therapy in chronic venous insufficiency. Int J Mol Med. 2006;18(1):215-219.

52. Rabe E, Partsch H, Hafner J, et al. Indications for medical compression stockings in venous and lymphatic disorders: an evidence-based consensus statement. Phlebology. 2018;33(3):163- 184.

53. Ricolfi L, Reverdito V, Gabriele G, et al. Micromassage compression leggings associated with physical exercise: pilot study and example of evaluation of the clinical and instrumental effectiveness of conservative treatment in lipedema. Life (Basel). 2024;14(7):854.

54. Herrera-Ramos E, Cazaña-Pérez V, Forner- Cordero I, et al. Seguridad y eficacia del uso de prendas de compresión en el tratamiento del lipedema. Informes de Evaluación de Tecnologías Sanitarias. Ministerio de Sanidad. Servicio de Evaluación del Servicio Canario de la Salud; 2024.

55. Miller A, Krahl S, Möckel L. Treatment approaches with compression therapy for lipedema a meta-analysis on the effect on pain. Phlebologie 2024;53(01):10-15.

56. Szolnoky G, Forner-Cordero I. Compression in lipedema. In: Mosti G, Partsch H, eds. Compression Therapy. Edizioni Minerva Medica; 2022:137-140.

57. Kankam HKN, Lim CS, Fiorentino F, Davies AH, Gohel MS. A summation analysis of compliance and complications of compression hosiery for patients with chronic venous disease or postthrombotic syndrome. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2018;55(3):406-416.

58. Paling I, Macintyre L. Survey of lipoedema symptoms and experience with compression garments. Br J Community Nurs. 2020;25(Suppl 4):S17-S22.

59. Forner-Cordero I, Aparicio I, Blanes- Martínez M, Blanes-Company M, Gisbert-Ruiz M. Analysis of a survey on compression garments in patients with lipedema. Paper presented at: 28th ISL World Congress of Lymphology. September 20-24, 2021; Athens, Greece.

60. Hagedoren-Meuwissen E, Roentgen U, Zwakhalen S, van der Heide L, van Rijn MJ, Daniëls R. The impact of wearing compression hosiery and the use of assistive products for donning and doffing: a descriptive qualitative study into user experiences. PLoS One. 2024;19(12):e0316034.