Early thrombus removal in the oncology patient

Matthew J. Mullins, MD, PhD

Consultant Interventional Radiologist, Galway University, Hospital, Galway, Ireland

Gerard O’Sullivan, FRCR, FRCPI, F CIRSE, F SIR

Professor of Interventional Radiology, Galway University, Hospital, Galway, Ireland

ABSTRACT

In this review article, we will explore the treatment options and clinical considerations in the setting of hospital presentations with acute/subacute thrombosis in the oncology patient. This a complex disease spectrum that leads to significant morbidity, health care costs, and increased hospital visits and admissions over time. Cancer-associated thrombosis has become a significant cause of morbidity and potential mortality in the oncology patient. Along with challenging treatment regimens and clinical dysfunction caused by the primary underlying disease, thrombosis poses a significant threat to life, functional status, and long-term health. Early thrombus removal in the cancer patient is emerging as an important strategy in managing this complex problem and attempting to limit the immediate consequences such as life-threatening pulmonary embolus and long-term consequences such as postthrombotic syndrome.

We discuss and critique the current literature supporting early thrombus removal and the strategies we employ at our institution to manage this challenging patient cohort. Controversies exist including side effect profiles of various treatment options, theoretical increased bleeding risk, long-term anticoagulation suitability, and overall survival benefit depending on life expectancy. Overall, we advocate for establishing a robust hospital policy detailing the interventional management of acute thrombosis that is readily accessible and regularly advertised to clinicians. Notwithstanding an established pathway, there is still significant nuance to the decision-making algorithm that must ultimately put the patient at the center of all decisions and interventions. The future of managing oncology patients with acute thrombosis is to inform our decision-making by having dedicated trials aimed at comparing interventional management options in randomized controlled trials with a specific focus on this patient cohort.

Introduction

Cancer-associated thrombosis is a common occurrence in the oncology patient population with an incidence of between 5% and 20% or put differently it occurs at a rate 4 to 7 times higher in patients with malignancy compared with the general population.1-3 Some papers have reported up to a 15-fold increased risk.4 Thrombosis results in significant associated morbidity and mortality. Cancer has been found in up to 5% of patients with an unprovoked venous thromboembolism (VTE).1,5,6

VTE has been shown to be the second leading cause of death in cancer patients secondary to disease progression and in close proximity to infection as a cause of mortality other than the cancer itself.7,8

Trousseau first described the link between cancer and venous thrombosis. This initial discovered link has been consistently proven for over 100 years.9 The incidence is up to 100 cases per 100 000 people in the general population of which approximately 33% of patients will meet diagnostic criteria for pulmonary embolism (PE).

The incidence of acute VTE has been proven to be significantly higher in the cancer patient cohort. Clinically significant VTE can be seen in up to 15% of patients. This represents a significant health care burden.

Specific risk factors for oncology patients include metastatic disease and treatment-induced risk, including immunotherapies, and this increased risk stems from a complex interplay of tumor biology, prothrombotic factors, therapeutic interventions, and patient-related variables.

In 2008 in Lancet Oncology, Noble et al published an important systematic review and meta-analysis assessing the current practice guidelines for patients with acute VTE in high-risk cancer patients.10 Since this paper, there have been a number of further studies reviewing management of this vulnerable patient cohort.11-13

Traditionally, the cornerstone of thrombus management in cancer has been anticoagulation. However, certain clinical scenarios demand a more aggressive approach. Early thrombus removal—through catheter-directed thrombolysis (CDT), mechanical thrombectomy, or surgical intervention—is increasingly considered in patients with severe thrombotic complications, such as massive PE, phlegmasia cerulea dolens, or critical limb ischemia.14

Whereas the benefits of early thrombus removal are well-recognized in the general population, their application in oncology is more nuanced. The inherent bleeding risk, chemotherapy-induced cytopenias, and overall prognosis must be carefully balanced against the potential gains of thrombus extraction. Yet, with improving technology and multidisciplinary collaboration, selected cancer patients may experience significant clinical benefit from early thrombus removal strategies.

This article explores the pathophysiology, diagnostic approach, indications, and techniques of early thrombus removal in oncology patients. It also highlights evidence-based recommendations, emerging data, and clinical considerations unique to the cancer population. A multidisciplinary framework is emphasized to ensure optimal, individualized patient care.

Pathophysiology of thrombosis in cancer

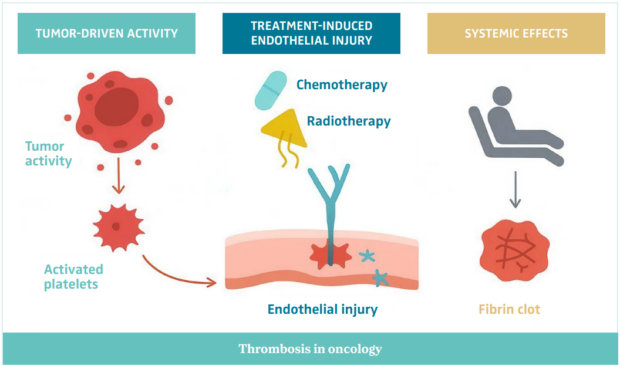

Thrombosis in the context of cancer (Figure 1) is a multifactorial process driven by the intricate interaction between malignancy, host response, and therapeutic interventions. The phenomenon was first described by Armand Trousseau in the 19th century as mentioned previously and is now recognized as a hallmark of cancer progression and a key contributor to cancer-related mortality.9

Figure 1. An illustration of the pathophysiology of thrombosis in oncology.

Abbreviations: IL-1β, interleukin 1-beta; TF, tissue factor; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor alpha; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

Hypercoagulability and the cancer state

Cancer induces a hypercoagulable state through several direct and indirect mechanisms. Tumor cells can express and release procoagulant substances such as tissue factor (TF), cancer procoagulant, and inflammatory cytokines (eg, interleukin-6, tumor necrosis factor-α), which activate the coagulation cascade. TF, in particular, plays a central role in initiating thrombin generation, leading to fibrin clot formation.

Moreover, tumor cells interact with platelets, leukocytes, and endothelial cells, contributing to a prothrombotic microenvironment. This interaction can lead to platelet activation, endothelial injury, and the release of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs), all of which promote thrombogenesis.15-17

Tumor-specific factors

Certain cancers are more thrombogenic than others. Pancreatic, gastric, brain, and lung cancers, along with hematologic malignancies like lymphoma and multiple myeloma, are associated with a particularly high risk of VTE.18The stage and burden of disease also correlate strongly with thrombotic risk—advanced and metastatic cancers carry a significantly higher risk.19

Therapy-related factors

Cancer treatments further exacerbate thrombosis risk. Chemotherapy induces endothelial damage and systemic inflammation. Agents such as cisplatin, thalidomide, lenalidomide, and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) inhibitors are well-known to increase thrombotic risk. Hormonal therapies, including tamoxifen and aromatase inhibitors, also contribute to clot formation.

Radiation therapy can lead to local vascular injury and inflammation, particularly when involving the thoracic or pelvic vasculature. Central venous catheters (CVCs), frequently used in oncology, are another key contributor to thrombus formation, particularly in the upper extremities or central veins.17

Patient-related factors

Beyond cancer and its treatments, patient-specific factors—such as immobility, recent surgery, infection, obesity, and inherited thrombophilia—also contribute. Age and performance status further modulate individual risk.19

The resulting hypercoagulable state in cancer patients is thus a composite outcome of tumor biology, host response, and therapeutic exposure. This complex pathophysiology underscores the need for a tailored approach to both prevention and intervention, particularly when considering early thrombus removal.17

Clinical presentation and diagnosis

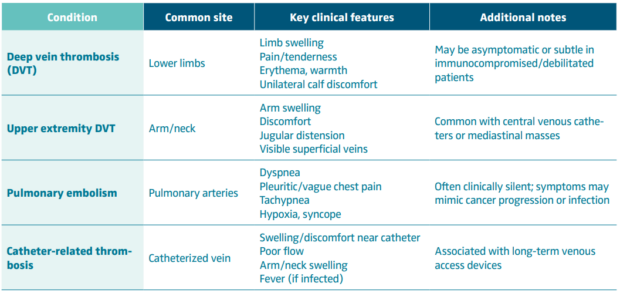

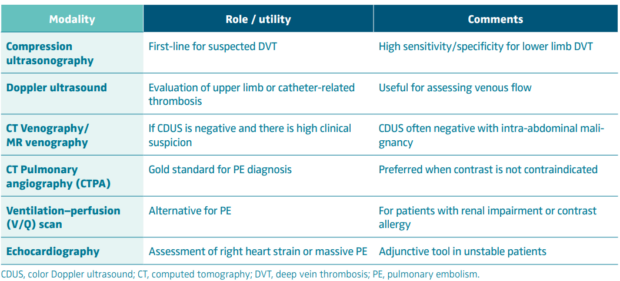

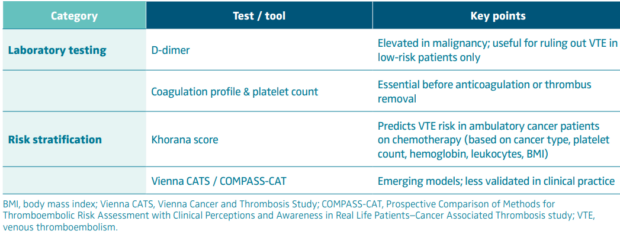

Timely recognition of thrombotic events in oncology patients is crucial, given the high morbidity and potential for rapid deterioration. However, the clinical presentation is often subtle, atypical, or masked by underlying malignancy or its treatment (Table I). Clinicians must maintain a high index of suspicion, especially in high-risk patients.

Early diagnosis is critical, particularly when considering advanced interventions like thrombus removal. Delay in recognition can lead to clot propagation, embolization, or postthrombotic complications—outcomes that are particularly dangerous in oncology patients with limited physiological reserve. Tables II and III describe diagnostic approaches to cancer-associated thrombosis, along with laboratory and risk assessment tools.

Clinical significance of acute VTE in oncology

VTE represents a major cause of morbidity and mortality among cancer patients, second only to progression of the underlying malignancy as a cause of death. The incidence of VTE varies by tumor type, stage, and treatment modality, but can exceed 20% in high-risk cohorts, particularly those with pancreatic, gastric, brain, or lung cancer.17 The consequences extend far beyond the acute event, influencing both short-term survival and long-term functional outcomes.

Acute morbidity is often substantial. Deep vein thrombosis (DVT), particularly when involving the iliofemoral or caval segments, can cause severe limb swelling, pain, and functional impairment. These symptoms can delay or interrupt chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or surgical interventions, thereby compromising oncologic control. PE carries a significant risk of sudden death and is frequently underdiagnosed in this population due to overlapping respiratory symptoms and the presence of comorbid conditions such as infection or tumor emboli. Cancer patients with VTE are at greater risk of recurrent events despite adequate anticoagulation, and they experience higher in-hospital mortality compared with non-cancer counterparts.

Chronic sequelae are equally important. Persistent venous obstruction and valvular damage lead to venous hypertension and the development of postthrombotic syndrome (PTS), characterized by chronic pain, edema, and skin changes, which may progress to ulceration. PTS affects up to 50% of patients following proximal DVT and significantly diminishes quality of life. In oncology, this morbidity compounds the physical and psychological burden of cancer and its treatments.20Reduced mobility and chronic limb symptoms can contribute to deconditioning, increased dependency, and reduced ability to tolerate ongoing therapy.

Catheter-associated thrombosis, particularly of the upper extremity or central veins, poses unique challenges. Central venous access is vital for chemotherapy, parenteral nutrition, and blood sampling. Thrombosis can necessitate catheter removal, interrupting essential treatment pathways, or lead to superior vena cava syndrome with significant symptomatic distress. Early thrombus removal strategies in this context may help maintain venous access and avoid treatment delays.

Moreover, VTE carries a prognostic implication in oncology. The occurrence of thrombosis is often a marker of biologically aggressive disease, correlating with higher tumor burden and poorer survival. This clinical reality provides a compelling rationale for considering early thrombus removal in selected patients to preserve function, enhance comfort, and sustain the delivery of cancer therapy.

Rationale for early thrombus removal

The concept of early thrombus removal arises from the recognition that anticoagulation alone, though effective at preventing thrombus extension and recurrence, does not actively lyse established clot or restore venous patency. In the oncology population, where thrombotic events often coincide with ongoing treatment, the persistence of obstructive thrombus can translate to prolonged pain, swelling, functional impairment, and interruption of cancer therapy. Early intervention aims to address these issues by physically or pharmacologically removing clot burden before irreversible venous wall and valve injury occurs.14,21

Timing is crucial. Experimental and clinical data indicate that thrombus organization begins within days of formation, leading to fibrosis and adhesion to the venous endothelium. When this has occurred, the success of thrombus dissolution or extraction declines markedly. The term early thrombus removal typically refers to intervention within 10–14 days of symptom onset, a window during which the thrombus remains friable and amenable to mechanical or pharmacologic clearance. Early restoration of venous flow can mitigate inflammation and prevent valvular reflux, thereby reducing the risk of PTS.

The potential benefits of early thrombus removal in oncology are multifaceted. From a symptomatic perspective, rapid decompression of venous obstruction provides prompt relief of pain and swelling, often restoring mobility and improving quality of life. Functionally, it may enable continuation of systemic cancer therapy without delay, preserve venous access routes, and prevent long-term complications that contribute to morbidity and hospital readmission. In younger or fitter oncology patients with good performance status, these benefits can be particularly meaningful, preserving independence and treatment tolerance.

Anticoagulation limitations are well-recognized. Despite appropriate therapy, up to half of patients with proximal DVT develop PTS within 2 years, and residual thrombus is a strong predictor of recurrence. Moreover, in cancer, persistent thrombosis may compromise limb function or necessitate cessation of indwelling catheters essential for chemotherapy. Thus, anticoagulation alone may be insufficient in high-burden or anatomically critical thrombi.

Patient selection is fundamental. Candidates for early thrombus removal typically present with extensive iliofemoral or caval DVT, severe symptoms, or limb-threatening venous congestion, and have a reasonable life expectancy (>6–12 months) with manageable bleeding risk. Conversely, patients with advanced metastatic disease, thrombocytopenia, or recent major surgery may be unsuitable. A careful multidisciplinary assessment—including oncology, interventional radiology, vascular medicine, and hematology—is essential to balance procedural benefits against hemorrhagic risk.

In summary, early thrombus removal seeks not merely to reduce clot burden but to preserve function, maintain quality of life, and sustain cancer treatment continuity. When judiciously applied, it represents an important adjunct to anticoagulation in selected oncology patients with acute, extensive venous thrombosis.

Evidence base

The evidence supporting early thrombus removal has evolved over the past two decades through a series of randomized controlled trials and observational studies—though, notably, patients with active malignancy have been largely underrepresented in these datasets. Consequently, most current recommendations for oncology patients rely on extrapolation from broader VTE populations.

Trials in the general population

The CaVenT trial (Catheter-Directed Venous Thrombolysis in Acute Iliofemoral Vein Thrombosis; 2012) was among the first randomized studies to demonstrate a potential benefit of CDT. Involving 209 patients with acute iliofemoral DVT, the study found that CDT, in addition to anticoagulation, reduced the incidence of PTS at 2 years (41% vs 56%) and improved iliofemoral patency. However, major bleeding occurred in 3% of patients. Importantly, those with active cancer were excluded, limiting direct applicability to oncology populations.22

The ATTRACT trial (Acute Venous Thrombosis: Thrombus Removal with Adjunctive Catheter-Directed Thrombolysis; 2017), the largest to date, randomized 692 patients with proximal DVT to pharmacomechanical CDT (PCDT) or standard anticoagulation alone. Overall, PCDT did not significantly reduce the rate of PTS at 24 months, although it was associated with faster symptom relief and improved quality-of-life measures in the iliofemoral DVT subgroup. The trial confirmed a higher bleeding risk (1.7% vs 0.3%) with intervention but again excluded patients with active malignancy, citing their heightened hemorrhagic risk and limited life expectancy.23

The CAVA trial (Ultrasound-Accelerated Catheter-Directed Thrombolysis versus Anticoagulation for the Prevention of Postthrombotic Syndrome; 2020) evaluated ultrasound-accelerated CDT versus anticoagulation alone, showing a trend toward lower PTS rates but no statistically significant benefit. Bleeding risk remained a concern, and as with previous trials, patients with cancer were excluded. Collectively, these trials demonstrate that while early thrombus removal can restore patency and improve short-term symptoms, its role in preventing long-term complications remains debated.24

Observational and subgroup data in oncology

Oncology-specific evidence consists mainly of retrospective case series, institutional experiences, and registry data. These reports suggest that thrombectomy and low-dose CDT can be performed safely in selected cancer patients, particularly with modern devices and careful monitoring. Major bleeding rates range from 0% to 5%, lower than historically expected, and technical success rates often exceed 90%.

A retrospective study by Bækgaard et al (published in 2014) included 22 cancer patients undergoing CDT for iliofemoral DVT, reporting significant symptom improvement and acceptable bleeding risk.25 Similarly, small institutional series have described successful pharmacomechanical thrombectomy using devices such as AngioJet and Lightning 12/16, often achieving rapid recanalization without thrombolytic infusion.26,27 Although promising, these studies are limited by small sample sizes, heterogeneity in cancer types, and absence of long-term follow-up.

Guideline perspectives

Contemporary guidelines reflect the limited oncology data. The Society of Interventional Radiology (SIR), European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS), and American Society of Hematology (ASH) all recommend considering early thrombus removal in selected patients with acute iliofemoral DVT, severe symptoms, and low bleeding risk—but none issue specific guidance for cancer patients. The consensus emphasizes multidisciplinary evaluation and individualized care, acknowledging the need for dedicated studies in this population.28-30

Evidence summary

In summary, whereas high-level evidence supports early thrombus removal in well-selected non-cancer patients, data specific to oncology remain scarce. The available retrospective experience suggests that with modern techniques and careful selection, intervention can be safe and effective. However, the absence of prospective oncology-focused trials continues to limit definitive recommendations, underscoring the need for targeted research in this complex and high-risk population.

Risks and challenges

Whereas early thrombus removal offers the potential for rapid symptom relief and prevention of postthrombotic complications, its application in oncology is constrained by unique risks and clinical complexities. The decision to intervene requires careful balancing of the potential benefits of venous patency restoration against the heightened susceptibility to bleeding, infection, and procedural complications inherent to this population.

Bleeding risk represents the most significant challenge. Cancer patients frequently exhibit multiple hemostatic abnormalities—thrombocytopenia from chemotherapy, disseminated intravascular coagulation, hepatic dysfunction, and mucosal tumor involvement—all of which amplify the risk of hemorrhage. Systemic thrombolysis carries prohibitive bleeding rates in this context, and even CDT and pharmacomechanical thrombectomy may precipitate clinically relevant bleeding, particularly when thrombolytics are used. The risk is accentuated in patients with gastrointestinal or genitourinary malignancies, brain metastases, or recent surgery. Consequently, purely mechanical thrombectomy techniques are increasingly preferred where feasible, as they minimize or eliminate lytic exposure.

Procedure-related complications also merit consideration. Vascular injury, distal embolization, and access-site hematomas may occur, particularly in patients with friable or irradiated vessels. Catheter-directed therapies often require prolonged infusion times and intensive monitoring, which can be poorly tolerated by debilitated or immunocompromised patients. Moreover, oncology patients are at higher risk of infection and line sepsis, especially when central venous access is required for both thrombolysis and chemotherapy administration.

Another critical factor is patient prognosis. For individuals with advanced or metastatic disease, the survival benefit of thrombus removal may be marginal, and the procedural burden disproportionate. In such cases, palliative symptom control through compression therapy and anticoagulation may be more appropriate. Conversely, for patients with limited disease burden, good performance status, and longer expected survival, maintaining limb function and treatment continuity may justify a more aggressive interventional approach.

Resource and logistical considerations further complicate decision-making. Thrombectomy procedures require specialized expertise, imaging, and postprocedural surveillance, which may not be available in all centers. The need for multidisciplinary coordination between interventional radiology, oncology, hematology, and vascular medicine adds complexity but is essential for safe and effective care.31,32

Ultimately, the key challenge lies in individualizing therapy. No single algorithm can accommodate the heterogeneity of cancer types, patient comorbidities, and treatment goals. Decisions must be guided by tumor biology, anticipated bleeding risk, symptom burden, and patient preference. Meticulous selection, procedural planning, and periprocedural management are critical to minimizing complications while achieving meaningful clinical benefit.

Clinical decision-making framework

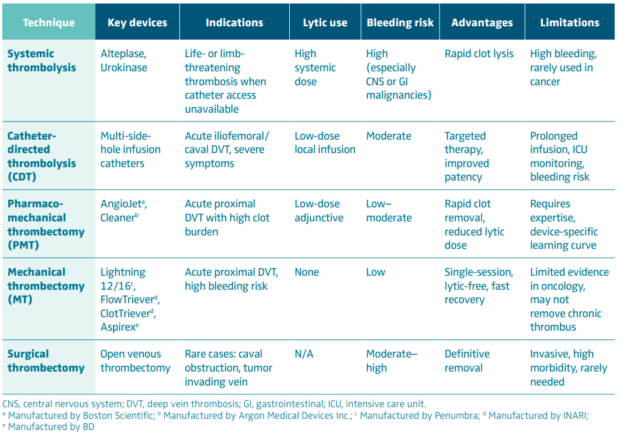

Early thrombus removal in oncology patients (Table IV) requires a multidisciplinary, patient-focused approach. Balancing thrombotic and bleeding risk, prognosis, and treatment goals mandates collaboration between interventional radiology, oncology, hematology, and vascular medicine.

Patient selection

Careful selection ensures safety and efficacy. Ideal candidates have: i) acute (<14 days) symptomatic iliofemoral or caval DVT with limb-threatening congestion or severe pain; ii) good performance status (ECOG [Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status scale], 0-2) and expected survival >6-12 months; iii) limited metastatic disease where mobility and venous access preservation are priorities; and iv) acceptable bleeding risk (platelets >75 x 109/L, no recent major surgery or intracranial metastases). Patients with advanced disease, poor function, or high bleeding risk are best managed conservatively with anticoagulation and compression therapy.

Procedural strategy

Technique selection should match the individual’s risk profile. Mechanical or pharmacomechanical thrombectomy is preferred in higher bleeding risk cases, whereas CDT may suit those with stable counts and low-risk tumor types. Key procedural principles include correction of coagulopathy, platelet optimization, ultrasound guidance, and minimal contrast use.

Multidisciplinary coordination

Close coordination between oncology, hematology, and interventional teams ensures timing avoids chemotherapy nadirs and optimizes anticoagulation management.

Shared decision-making

Given variable prognosis, patient preferences and goals of care must guide intervention. Discussions should address expected symptom relief, procedural risk, and recurrence potential.

At our institution, integrated oncology–interventional radiology (IR) referral pathways support timely intervention. Further education of medical and surgical teams could enhance awareness of the urgency of clot removal in cancer patients.

Future directions and ongoing trials

The management of thromboembolic disease in oncology is entering a new era, driven by technological innovation and a growing emphasis on individualized care. The future of early thrombus removal in cancer patients will depend on refining patient selection, minimizing procedural risk, and validating long-term outcomes through robust clinical trials.

Technological advancements

Recent progress in mechanical and aspiration thrombectomy devices—such as large-bore aspiration catheters (eg, FlowTriever, Lightning 12/16, Aspirex)—has transformed the interventional landscape. These systems enable efficient clot extraction without the need for thrombolytics, thereby reducing bleeding risk in patients with fragile hemostasis. Next-generation devices now incorporate ultrasound-assisted and rotational mechanisms to enhance efficacy in organized or chronic thrombus, potentially expanding the window for intervention beyond the traditional 14-day limit.

Parallel developments in intravascular imaging and artificial intelligence–assisted venous flow modeling may allow real-time assessment of thrombus composition and optimize device selection. Integration of imaging biomarkers could also improve prediction of thrombus chronicity and response to therapy in oncology-specific cohorts.

Research priorities

Despite technological gains, the evidence base for early thrombus removal in cancer remains limited. Existing trials, such as CaVenT, ATTRACT, and CAVA, largely excluded patients with malignancy. Dedicated studies are now underway to address this gap, including observational registries exploring outcomes of mechanical thrombectomy in cancer-associated iliofemoral DVT. Key end points include symptom resolution, bleeding complications, recurrence rates, and quality-of-life measures.

Precision thrombectomy

Ultimately, future care will likely adopt a precision-medicine approach, combining clinical, radiologic, and molecular data to guide individualized decisions. Interventional radiology is poised to play a central role in this evolution, bridging oncologic care and vascular medicine to improve survival, preserve limb function, and enhance quality of life.

Conclusion

VTE represents a significant source of morbidity and mortality in oncology patients. Oral anticoagulation plays an essential role but often fails to address the immediate symptom burden or prevent long-term venous complications. Early thrombus removal using CDT, pharmacomechanical thrombectomy, or purely mechanical thrombectomy offers the potential to restore venous patency, relieve symptoms, and preserve limb function.

The rationale for intervention is strongest in patients with acute, extensive proximal DVT, good performance status, and manageable bleeding risk, where procedural benefits can translate into maintained mobility, uninterrupted cancer therapy, and improved quality of life. However, oncology patients do present unique challenges including elevated hemorrhagic risk, comorbidities, and variability in prognosis. This necessitates an individualized multidisciplinary approach. Current evidence supporting early thrombus removal in cancer is limited, largely extrapolated from trials in the general population, highlighting the urgent need for oncology-specific prospective studies.

Advances in device technology and imaging-guided intervention have improved the safety and efficacy of thrombus removal, particularly for patients at high bleeding risk, and emerging research may soon enable precision-guided thrombectomy tailored to tumor biology and thrombus characteristics.

Our final thoughts are that early thrombus removal represents a promising adjunct to anticoagulation for selected oncology patients. Its judicious application, guided by patient goals, multidisciplinary collaboration, and evolving evidence can optimize clinical outcomes and enhance quality of life. This is all taken in the context of underscoring the importance of ongoing research to define best practices in this high-risk population.

CORRESPONDING AUTHOR

Dr Matthew J. Mullins

Radiology Department, University, Hospital Galway, Ireland, H91 YR71

email: mullinmj@tcd.ie

Professor Gerard O’Sullivan received an honorarium from Servier for the writing of this article.

References

1. Guntupalli SR, Spinosa D, Wethington S, Eskander R, Khorana AA. Prevention of venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer. BMJ. 2023;381:e072715.

2. Lip GY, Chin BS, Blann AD. Cancer and the prothrombotic state. Lancet Oncol. 2002;3(1):27-34.

3. Stein PD, Beemath A, Meyers FA, Skaf E, Sanchez J, Olson RE. Incidence of venous thromboembolism in patients hospitalized with cancer. Am J Med. 2006;119(1):60-68.

4. Khan F, Tritschler T, Marx CE, et al. Predictors of recurrent venous thromboembolism and bleeding in patients with cancer: a meta-analysis. Eur Heart J. 2025:ehaf453.

5. Bastounis EA, Karayiannakis AJ, Makri GG, Alexiou D, Papalambros EL. The incidence of occult cancer in patients with deep venous thrombosis: a prospective study. J Intern Med. 1996;239(2):153-156.

6. Prandoni P, Lensing AW, Büller HR, et al. Deep-vein thrombosis and the incidence of subsequent symptomatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 1992;327(16):1128-1133.

7. Khorana AA. Venous thromboembolism and prognosis in cancer. Thromb Res. 2010;125(6):490-493.

8. Khorana AA, Francis CW, Culakova E, Kuderer NM, Lyman GH. Thromboembolism is a leading cause of death in cancer patients receiving outpatient chemotherapy. J Thromb Haemost. 2007;5(3):632-634.

9. Trousseau A. Phlegmasia alba dolens. Clinique medicule de l’Hotel-Dieu de Paris. 1865;3:94.

10. Noble SI, Shelley MD, Coles B, et al. Management of venous thromboembolism in patients with advanced cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9(6):577-854.

11. Malgor RD, Gasparis AP. Pharmaco-mechanical thrombectomy for early thrombus removal. Phlebology. 2012;27(Suppl 1):155-162.

12. Laporte S, Benhamou Y, Bertoletti L, et al. Management of cancer-associated thromboembolism in vulnerable population. Arch Cardiovasc Dis. 2024;117(1):45-59.

13. Laporte S, Benhamou Y, Bertoletti L, et al; INNOVTE TAC Working Group; Groupe de travail INNOVTE CAT. [Translation into French and republication of: “Management of cancer-associated thromboembolism in vulnerable population”]. Rev Med Interne. 2024;45(6):366-381.

14. Meissner MH. Rationale and indications for aggressive early thrombus removal. Phlebology. 2012;27(Suppl 1):78-84.

15. Caine GJ, Stonelake PS, Lip GY, Kehoe ST. The hypercoagulable state of malignancy: pathogenesis and current debate. Neoplasia. 2002;4(6):465-473.

16. Zhang Y, Zeng J, Bao S, et al. Cancer progression and tumor hypercoagulability: a platelet perspective. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2024;57(6):959-972.

17. Wan T, Song J, Zhu D. Cancer-associated venous thromboembolism: a comprehensive review. Thromb J. 2025;23(1):35.

18. Moik F, Ay C, Pabinger I. Risk prediction for cancer-associated thrombosis in ambulatory patients with cancer: past, present and future. Thromb Res. 2020;191(Suppl 1):S3-S11.

19. Mulder FI, Horváth-Puhó E, van Es N, et al. Venous thromboembolism in cancer patients: a population-based cohort study. Blood. 2021;137(14):1959-1969.

20. Nawasrah J, Zydek B, Lucks J, et al. Incidence and severity of postthrombotic syndrome after iliofemoral thrombosis – results of the Iliaca-PTS – Registry. Vasa. 2021;50(1):30-37.

21. Plotnik AN, Haber Z, Kee S. Early thrombus removal for acute lower extremity deep vein thrombosis: update on inclusion, technical aspects, and postprocedural management. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2024;47(12):1595-1604.

22. Enden T, Haig Y, Kløw NE, et al. Long-term outcome after additional catheter-directed thrombolysis versus standard treatment for acute iliofemoral deep vein thrombosis (the CaVenT study): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2012;379(9810):31-38.

23. Vedantham S, Goldhaber SZ, Julian JA, et al. Pharmacomechanical catheter-directed thrombolysis for deep-vein thrombosis. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(23):2240-2252.

24. Notten P, Ten Cate-Hoek AJ, Arnoldussen CWKP, et al. Ultrasound-accelerated catheter-directed thrombolysis versus anticoagulation for the prevention of post-thrombotic syndrome (CAVA): a single-blind, multicentre, randomised trial. LancetHaematol. 2020;7(1):e40-e49.

25. Bækgaard N. Benefit of catheter-directed thrombolysis for acute iliofemoral DVT: myth or reality? Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2014;48(4):361-362.

26. Li JW, Xue J, Guo F, Han L, Ban RB, Wu XL. Clinical comparison of the efficacy of systemic thrombolysis, catheter-directed thrombolysis, and AngioJet percutaneous mechanical thrombectomy in acute lower extremity deep venous thrombosis [Article in Chinese]. Zhongguo Yi Xue Ke Xue Yuan Xue Bao. 2023;45(3):410-415.

27. Pandya YK, Tzeng E. Mechanical thrombectomy devices for the management of pulmonary embolism. JVS Vasc Insights. 2024:2:100053.

28. Gerhard-Herman MD, Gornik HL, Barrett C, et al. 2016 AHA/ACC Guideline on the management of patients with lower extremity peripheral artery disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on clinical practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69(11):e71-e126.

29. Kakkos SK, Gohel M, Baekgaard N, et al. Editor’s Choice – European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS) 2021 Clinical practice guidelines on the management of venous thrombosis. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2021;61(1):9-82.

30. Ortel TL, Neumann I, Ageno W, et al. American Society of Hematology 2020 guidelines for management of venous thromboembolism: treatment of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. Blood Adv. 2020;4(19):4693-4738.

31. O’Sullivan GJ, Waldron D, Mannion E, Keane M, Donnellan PP. Thrombolysis and iliofemoral vein stent placement in cancer patients with lower extremity swelling attributed to lymphedema. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2015;26(1):39-45.

32. Rahmani G, O’Sullivan GJ. Lessons learned with venous stenting: in-flow, outflow, and beyond. Tech Vasc Interv Radiol.2023;26(2):100897.