Neoplastic obstruction of the inferior vena cava: surgical approach

Alejandro Rodríguez-Morata, PhD, MD

Angiology and Vascular Surgery Department, Quirónsalud Málaga Hospital, Spain

Juan Pedro Reyes-Ortega, MD

Angiology and Vascular Surgery Department, Quirónsalud Málaga Hospital, Spain

María Luisa Robles-Martín, MD

Angiology and Vascular Surgery Department, Quirónsalud Málaga Hospital, Spain

Laura Gallego-Martín, MD

Angiology and Vascular Surgery Department, Quirónsalud Málaga Hospital, Spain

Patricio David Viteri-Estévez, MD

Angiology and Vascular Surgery Department, Quirónsalud Málaga Hospital, Spain

ABSTRACT

Neoplastic obstruction of the inferior vena cava (IVC) constitutes arare but formidable challenge in both vascular and oncologic surgery.It may arise from primary tumors originating within the vessel wall,such as leiomyosarcomas, or more frequently as secondary invasionor tumor thrombus from adjacent malignancies, including renal cellcarcinoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, or adrenal cortical carcinoma. Theanatomic complexity of the IVC, its proximity to vital structures, andthe hemodynamic consequences of obstruction demand a thoroughunderstanding of tumor characteristics, precise preoperative imaging,and meticulous surgical planning. This chapter provides a comprehensivereview of the classification, diagnostic workup, and detailed surgicaltechniques used to manage neoplastic IVC obstruction. We explore theroles of segmental resection, reconstruction techniques, and the useof advanced bypass methods, including cardiopulmonary bypass forintracardiac tumor extension. Outcomes, complications, and long-termprognosis are discussed, emphasizing the importance of an aggressive,multidisciplinary approach to optimize patient survival and quality of life.

Introduction

The inferior vena cava (IVC) is the major conduit for venous return from the lower extremities, pelvis, and abdominal viscera to the right atrium of the heart. Neoplastic obstruction of the IVC, although an infrequent clinical entity, represents a significant surgical and oncological challenge due to the vessel’s critical role and intricate anatomical relationships. Neoplastic involvement may be classified as primary, originating from tumors such as leiomyosarcomas arising from the tunica media of the IVC wall, or secondary, arising from contiguous spread or tumor thrombus from malignancies in adjacent organs, notably the kidneys and liver.1,2

The clinical presentation of neoplastic IVC obstruction varies widely depending on the extent and level of involvement, ranging from asymptomatic incidental findings to life-threatening complications such as Budd-Chiari syndrome or massive venous congestion. Surgical management remains the mainstay of treatment for resectable tumors, aimed at restoring venous patency and achieving local oncologic control. However, the complex anatomy, combined with the high risk of intraoperative complications, necessitates a multidisciplinary approach, including vascular surgeons, cardiac surgeons, oncologists, radiologists, and anesthesiologists.3,4

Classification of neoplastic IVC obstruction

Accurate classification of IVC tumors is essential to guide surgical planning and prognostication. The most widely accepted classification divides tumors based on their anatomical location relative to key landmarks such as the renal and hepatic veins and the diaphragm.5

• Level I: Tumors confined to the infrarenal segment of the IVC, below the renal veins.

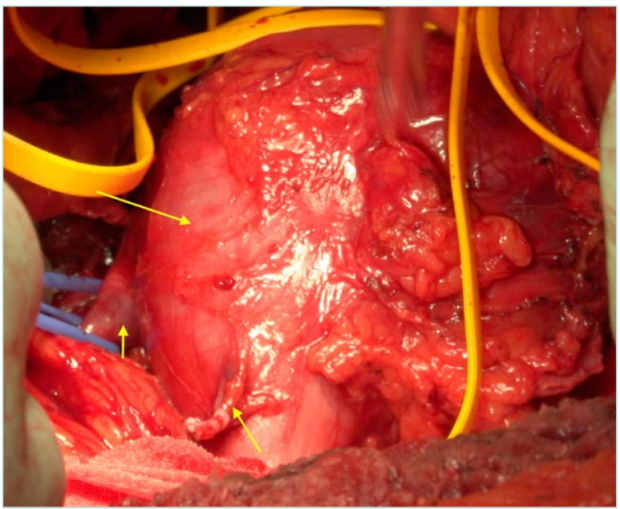

• Level II: Tumors involving the IVC between the renal and hepatic veins, often the most common location for primary leiomyosarcomas (Figure 1).

• Level III: Suprahepatic involvement extending up to the right atrium, requiring more extensive surgical access.

• Level IV: Tumors with intracardiac extension into the right atrium, representing the most advanced stage and necessitating complex cardiothoracic procedures.6,7

This stratification is pivotal, as higher-level tumors often require cardiopulmonary bypass, hypothermic circulatory arrest, or thoracoabdominal approaches, whereas lower-level tumors may be addressed via abdominal access alone.

Figure 1. Inferior vena cava (IVC) leiomyosarcoma, ranging from the infrarenal to the adrenal part. Short arrow: right renal vein. Intermediate arrow: right gonadal vein. Long arrow: IVC leiomyosarcoma.

Primary tumors of the IVC

Primary neoplasms of the IVC are rare, with leiomyosarcoma being the most frequently reported histological type. These tumors derive from the smooth muscle cells of the venous wall and show a predilection for the middle segment of the IVC (Level II).9 The aggressive nature of leiomyosarcomas manifests in rapid local progression, a high rate of local recurrence after resection, and the potential for distant metastases.7

Clinically, patients may report nonspecific symptoms such as vague abdominal or flank pain, lower limb edema due to venous obstruction, or symptoms consistent with Budd-Chiari syndrome when the suprahepatic IVC is involved.10 Preoperative diagnosis relies on imaging and tissue biopsy; however, biopsy must be approached with caution due to the risk of tumor seeding and hemorrhage.11

Secondary involvement of the IVC

More commonly than primary tumors, the IVC is involved secondarily through direct invasion or tumor thrombus propagation from neighboring malignancies. Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is the most frequent culprit, with tumor thrombus extending into the IVC in up to 10% of cases, occasionally reaching the right atrium.12,13 Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) may invade the hepatic veins and the suprahepatic IVC, whereas adrenal cortical carcinomas and retroperitoneal sarcomas are less common sources.14

Surgical management in these cases often involves en bloc resection of the tumor thrombus together with nephrectomy or hepatectomy depending on the primary tumor site. This complex surgery requires preoperative planning and intraoperative strategies tailored to the extent of vascular involvement.15

Preoperative imaging and planning

Accurate preoperative imaging is indispensable for delineating tumor extent, vascular involvement, and surgical feasibility. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) remains the cornerstone modality, providing detailed anatomic information on tumor size, location, and involvement of adjacent structures. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) offers superior soft tissue contrast and is especially valuable in assessing Level III and IV tumors with possible intracardiac extension.16

Transesophageal echocardiography is routinely employed for real-time evaluation of intracardiac tumor thrombus, crucial for surgical planning.17 Additionally, venography and intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) can provide valuable insights into intraluminal tumor characteristics and venous flow dynamics.18 A comprehensive assessment including renal function and cardiopulmonary status is mandatory, and all findings should be reviewed in a multidisciplinary tumor board to optimize surgical strategy.19

Techniques of IVC resection

The overarching surgical objective is complete oncologic resection with restoration of adequate venous return. Complete excision with negative margins is essential to minimize local recurrence and improve survival outcomes. Preservation of contralateral renal vein drainage is critical to maintain renal function. Surgeons must take great care to avoid tumor fragmentation that can precipitate pulmonary embolism or systemic dissemination.2,20

Venous reconstruction is often necessary after tumor resection to maintain hemodynamic stability and prevent venous hypertension. Patient selection is guided by functional status, presence of distant metastases, and extent of tumor invasion; unresectable metastases and poor performance status contraindicate aggressive surgery.21

The surgical management of neoplastic obstruction of the IVC requires tailored approaches based on the tumor’s location, extent, and involvement of adjacent structures. The techniques can be broadly categorized as follows:

Segmental cavectomy

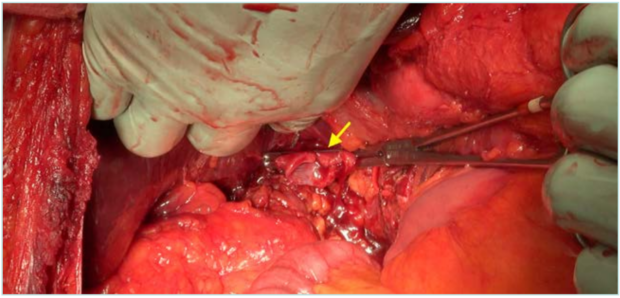

Segmental cavectomy involves resecting the affected segment of the IVC en bloc with the tumor (Figure 2). This technique is the standard for localized tumors, especially those confined to the infrarenal or juxtarenal portions of the IVC, where vascular control is more accessible. Surgical exposure is achieved via laparotomy or thoracoabdominal approaches depending on tumor level.7,9

Figure 2. Cavectomy and inferior vena cava (IVC) clamping at the infrahepatic level, ready for vascular reconstruction. Arrow: clamped edge of the IVC.

The procedure begins with careful proximal and distal vascular control to prevent hemorrhage and embolization. This is followed by meticulous dissection to separate the tumor-bearing segment from adjacent organs, such as the duodenum, pancreas, or renal structures, preserving vital anatomy. The segment is then excised en bloc with oncologic principles of negative margins.8

Reconstruction depends on the length and location of the resected segment. Short resections may allow primary anastomosis, whereas longer segments require patch repair or graft interposition. Segmental cavectomy offers the advantage of complete tumor removal and is associated with favorable oncologic outcomes in selected patients.22

Primary closure and patch reconstruction

After tumor excision, small defects of the IVC wall may be closed primarily if the luminal diameter and venous flow can be preserved without significant stenosis. This approach is feasible in cases where the resection does not involve extensive circumferential vessel wall loss.10

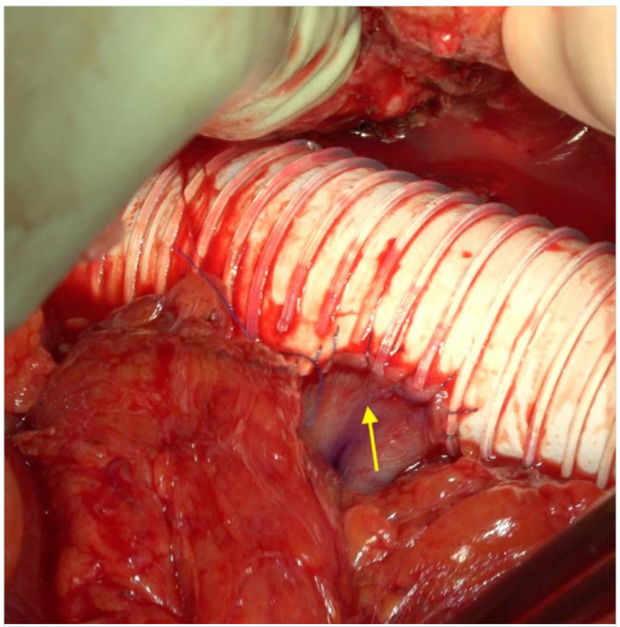

When larger defects exist, primary closure risks narrowing the lumen and consequent venous hypertension, increasing the risk of thrombosis. In such cases, patch reconstruction is preferred. Autologous materials such as pericardium (either harvested from the patient or bovine derived) offer biocompatibility and durability, reducing infection risk. Synthetic patches like polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) are alternatives when autologous tissue is unavailable (Figure 3).4,14

Patch cavoplasty restores venous continuity and preserves flow dynamics, minimizing postoperative venous congestion.

Figure 3. Reimplantation of the right renal vein in the polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) body. Arrow: right renal vein.

Cavocaval and atriocaval bypass

In cases of extensive IVC involvement or when prolonged cross-clamping threatens venous return and hemodynamic stability, bypass techniques are employed. Cavocaval bypass entails creating an alternative venous route around the resection site using prosthetic grafts, allowing continuous drainage of lower extremity and abdominal venous blood.11

The choice of material depends on surgeon preference, availability, and patient-specific factors.7

Interposition grafts

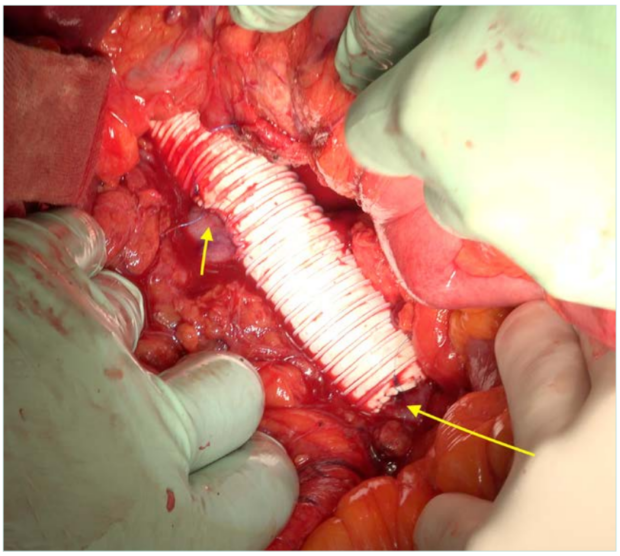

When resection results in a full circumferential loss of a segment of the IVC, interposition grafting becomes necessary to reestablish venous return. Prosthetic grafts such as PTFE or Dacron are widely used due to their availability and ease of handling (Figure 4). These grafts provide reliable patency but carry a risk of infection, particularly in contaminated fields or prolonged surgeries.12

Figure 4. End-to-end bypass reconstruction between the inferior vena cava (IVC) immediately proximal to its iliocaval bifurcation and the retrohepatic zone. Short arrow: right renal vein reimplanted. Long arrow: distal anastomosis, close to the bifurcation.

Alternatively, autologous vein grafts, typically harvested from the femoral vein or superficial femoral vein, may reduce infection risk and offer better biocompatibility. However, vein harvesting adds complexity, increases operative time, and introduces donor site morbidity.23

Graft sizing is critical to maintain laminar flow and avoid turbulence, which predisposes to thrombosis. Oversized grafts may cause stasis, whereas undersized grafts can cause outflow obstruction. Postoperative anticoagulation protocols should be adapted accordingly to enhance graft patency.6

For tumors with intracardiac extension, atriocaval bypass is performed, involving cannulation of the right atrium and the IVC to maintain systemic venous return during complex resections. These bypasses provide a bloodless surgical field and prevent venous congestion, enabling safe tumor excision even in challenging cases.20

Bypass procedures require careful coordination between vascular and cardiothoracic teams and meticulous intraoperative management to avoid complications such as air embolism or hemodynamic instability.19

Techniques with cardiopulmonary bypass

Level III and IV tumors extending into the right atrium necessitate the use of cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) to safely resect intracardiac tumor thrombi. CPB provides circulatory and respiratory support, allowing the surgeon to open the right atrium (atriotomy) under controlled conditions.4,24

Hypothermic circulatory arrest may be employed in complex cases to reduce metabolic demands and provide a bloodless field, facilitating complete tumor removal. CPB reduces intraoperative blood loss, supports systemic circulation, and improves surgical visualization.8

Post-CPB management involves careful hemodynamic support and monitoring for coagulopathy, given the effects of extracorporeal circulation on platelet function and coagulation cascades.2

Management of suprahepatic and intracardiac extension

Tumors that involve the suprahepatic IVC and extend into the right atrium present formidable surgical challenges requiring combined thoracoabdominal approaches. A median sternotomy combined with laparotomy is often necessary to provide adequate exposure of the heart, IVC, and liver.22

Hypothermic circulatory arrest during CPB facilitates tumor excision under optimal conditions by minimizing blood flow and reducing tissue oxygen demand. This technique allows safe removal of tumor thrombi extending into cardiac chambers and reduces the risk of embolization.17

Following tumor removal, reconstruction of the IVC and atrial walls is performed, often requiring patch angioplasty or graft interposition to restore venous continuity. Hepatic mobilization may be necessary to access the suprahepatic IVC fully. Additionally, hepatic vein reconstruction may be required to maintain adequate liver drainage and function.6

These complex procedures demand careful perioperative planning, multidisciplinary expertise, and advanced surgical skills to balance oncologic radicality with preservation of vital functions.7

Postoperative care and complications

The postoperative management of patients undergoing surgical treatment for neoplastic obstruction of the IVC is complex and demands a multidisciplinary and highly vigilant approach. Given the extensive nature of the surgery, the involvement of major vascular structures, and the potential for significant hemodynamic alterations, meticulous postoperative care is essential to optimize outcomes and reduce morbidity and mortality.20

Hemodynamic monitoring: Close hemodynamic monitoring in an intensive care setting is mandatory immediately after surgery. Due to the manipulation, resection, and reconstruction of the IVC, patients are at high risk for fluctuations in venous return and cardiac output. Continuous monitoring of central venous pressure, arterial pressure, urine output, and cardiac function allows early detection of hemodynamic instability, fluid imbalances, or cardiac complications. Advanced monitoring techniques, including pulmonary artery catheterization or transesophageal echocardiography, may be indicated in select cases to guide fluid management and inotropic support.11

Anticoagulation and thromboprophylaxis: Preventing graft thrombosis is a critical component of postoperative care. Patients who undergo IVC resection and reconstruction are inherently at risk for venous thromboembolism due to endothelial injury, altered flow dynamics, and the hypercoagulable state often associated with malignancy. A carefully tailored anticoagulation regimen should be initiated early, balancing the risk of bleeding with thrombosis. Low molecular weight heparin or unfractionated heparin protocols are commonly employed initially, transitioning to oral anticoagulants as clinically appropriate. Regular assessment of coagulation parameters and vigilant monitoring for signs of bleeding or thrombosis is imperative.14

Surveillance imaging: Early postoperative imaging plays a vital role in identifying complications and assessing graft patency. Doppler ultrasound is frequently used for bedside evaluation of venous flow within the reconstructed IVC or grafts. CT or MRI may be indicated to evaluate suspected thrombosis, graft infection, or other complications. Scheduled imaging during follow-up enables timely intervention in cases of graft stenosis or occlusion.23

Renal function and hepatic congestion: Given the central role of the IVC in venous drainage from the kidneys and liver, postoperative renal function requires close surveillance. Venous congestion resulting from impaired outflow can precipitate acute kidney injury. Serial measurement of serum creatinine, urine output, and electrolytes is essential. Similarly, hepatic congestion secondary to impaired IVC drainage may lead to liver dysfunction, manifesting as elevated liver enzymes, coagulopathy, or ascites. Early recognition and management, including optimization of volume status and hemodynamics, are critical to prevent progression.18

Common postoperative complications:

• Bleeding: The extensive vascular dissection and anticoagulation increase the risk of postoperative hemorrhage, which may necessitate re-exploration.2

• Graft thrombosis: Thrombosis of venous grafts or patches can lead to acute venous congestion and limb swelling, requiring urgent anticoagulation or thrombectomy.4

• Pulmonary embolism: Embolization of thrombus fragments or deep vein thrombosis remains a significant risk despite prophylaxis. Vigilance for respiratory symptoms and prompt diagnostic workup is mandatory.22

• Renal failure: Both acute tubular necrosis secondary to hypoperfusion and venous congestion contribute to renal impairment postoperatively. Renal replacement therapy may be necessary in severe cases.13

• Surgical site infections: Given the complexity and length of the surgery, patients are at risk for wound infections, which can be compounded by prosthetic grafts and immunosuppression. Strict aseptic technique and early antibiotic therapy are essential.9

Outcomes and prognosis

The long-term outcomes following surgical management of neoplastic obstruction of the IVC are influenced by several critical factors, including tumor histology, the completeness of surgical resection, and the presence or absence of metastatic disease at the time of surgery.19,20

Tumor histology plays a pivotal role in prognosis. Primary leiomyosarcomas of the IVC, despite being the most common primary tumor in this location, generally carry a guarded prognosis. These tumors are characterized by aggressive local behavior, high rates of local recurrence, and a significant propensity for distant metastases, often to the lungs or liver.10 The inherently infiltrative nature and biological aggressiveness of leiomyosarcomas limit long-term survival, with reported 5-year survival rates varying widely but generally remaining low. Nevertheless, selected patients who undergo complete surgical resection with negative margins followed by adjuvant therapies, such as radiotherapy or chemotherapy, may experience improved survival outcomes.12 However, the role of systemic therapy remains adjunctive and is not yet standardized,14 underscoring the importance of aggressive surgical management as the cornerstone of treatment.

In contrast, secondary involvement of the IVC, most notably by RCC, presents a different prognostic landscape. RCC with tumor thrombus extending into the IVC can be associated with relatively better postoperative outcomes, especially when the tumor thrombus is confined to the venous system without distant metastases. Surgical removal of the renal tumor combined with thrombectomy of the IVC thrombus can provide significant survival benefit and symptom relief. The extension level of the tumor thrombus, although a technical challenge, does not independently dictate prognosis if complete resection is achieved. Patients with nonmetastatic disease who undergo radical surgery can achieve 5-year survival rates that are markedly higher compared with patients with metastatic spread.12

Completeness of resection is arguably the most critical surgical factor influencing outcomes. Achieving an R0 resection, defined as complete tumor removal with microscopically negative margins, is strongly correlated with improved local control and overall survival.15 Incomplete resections or positive margins predispose patients to rapid local recurrence, which is frequently associated with worsening symptoms and reduced survival. Given the complexity of the IVC anatomy and tumor involvement, meticulous surgical technique, and thorough preoperative planning are essential to maximize the likelihood of achieving complete resection. The involvement of multidisciplinary teams including vascular, urologic, and cardiothoracic surgeons is often necessary for optimal oncologic clearance.21

The choice and success of venous reconstruction techniques after tumor resection also impact long-term patency and clinical outcomes. Reconstruction strategies must ensure durable venous return while minimizing complications such as thrombosis or graft infection. Use of autologous vein grafts or prosthetic materials like PTFE has shown favorable patency rates when performed under optimal conditions (Figure 5). Postoperative anticoagulation protocols tailored to the patient’s risk profile further contribute to graft longevity.23

Finally, patient selection and perioperative management are critical determinants of survival. Factors such as patient comorbidities, performance status, and absence of distant metastases influence both surgical candidacy and postoperative recovery.8 Meticulous perioperative care, including vigilant hemodynamic monitoring, early detection and management of complications, and rehabilitation, enhances functional outcomes and survival.

Conclusions

Neoplastic obstruction of the IVC is a rare but complex surgical condition requiring a tailored and multidisciplinary approach. Mastery of tumor classification, detailed preoperative imaging, and advanced surgical techniques are essential to optimize patient outcomes. Innovations in reconstruction

and extracorporeal support have expanded resectability and improved survival for selected patients. Vascular surgeons must continue leading the management of these challenging cases to deliver effective, evidence-based care.

CORRESPONDING AUTHOR

Dr Alejandro Rodríguez-Morata

Hospital Quirónsalud Málaga, Avenida Imperio Argentina, 1; 29004, Málaga, España

email: vascular@rodriguezmorata.es

Dr Alejandro Rodríguez-Morata received an honorarium from Servier for the writing of this article.

References

1. Herr HW, Schlossberg RE, Whitmore WF. Leiomyosarcoma of the inferior vena cava: a rare and difficult diagnosis. J Urol.2005;173(4):1220-1221.

2. Neves RJ, Zincke H. Surgical treatment of renal cancer with vena cava extension. Br J Urol. 1987;59(5):390-395.

3. Langan EM, Ferreira M, Sundaram C, et al. Multidisciplinary management of inferior vena cava tumors: a systematic review. J Surg Oncol. 2021;124(4):583-593.

4. Tsukuda H, Shimizu T, Yasui N, et al. Vascular reconstruction using bovine pericardial patch for inferior vena cava leiomyosarcoma. Ann Vasc Surg. 2017;44:261.e7-261.e10.

5. Mussi C, Casali PG, Lo Vullo S, et al. Inferior vena cava leiomyosarcoma: clinical experience with 15 cases. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14(1):353-360.

6. Thorson CM, Turaga KK, Reith JD, et al. Surgical management of inferior vena cava leiomyosarcoma: a single-institution experience. Ann Vasc Surg. 2013;27(8):1083-1090.

7. Wachtel H, Neuwirth MG, Cai L, et al. Surgical outcomes of resection of inferior vena cava leiomyosarcoma. Ann Vasc Surg. 2019;61:176-185.

8. Samaan S, Al-Haddad M, Aoun H, et al. Surgical techniques for tumors involving the inferior vena cava: review and classification. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2017;12(1):61.

9. Mingoli A, Cavallaro A, Sapienza P, et al. Primary leiomyosarcoma of the inferior vena cava: results of surgical treatment and prognosis. J Vasc Surg. 1997;26(5):768-775.

10. National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN). Soft tissue sarcoma guidelines, version 3.2023. [Internet] 2023. https://www.nccn.org

11. Kim SJ, Cho YP, Kim HY, et al. Role of transesophageal echocardiography in evaluation of tumor thrombus in renal cell carcinoma involving the inferior vena cava. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2014;28(2):342-346.

12. Herr HW, Schlossberg RE, Whitmore WF. Surgical management of renal cell carcinoma with vena cava thrombus. J Urol. 2005;173(4):1220-1221.

13. Blute ML, Leibovich BC, Lohse CM, et al. The Mayo Clinic experience with surgical management, complications and outcome for patients with renal cell carcinoma and venous tumour thrombus. BJU Int. 2004;94(1):33-41.

14. Minami T, Chikamoto A, Arii S. Hepatocellular carcinoma with tumor thrombus in the inferior vena cava and right atrium. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2004;11(6):376-379.

15. Iannelli A, Scardina L, Pellegrino L, et al. Inferior vena cava leiomyosarcoma: surgical management and outcome. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2018;51:101-106.

16. Padua RA, Belli AM, Curry A, et al. MRI in the evaluation of inferior vena cava tumour thrombus in renal cell carcinoma. Clin Radiol. 1995;50(8):517-520.

17. Abutaka A, Morikawa M, Miyamoto K, et al. Surgical resection of a right atrial tumor thrombus arising from renal cell carcinoma using hypothermic circulatory arrest. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011;17(5):469-472.

18. Groshar D, Gaitini D, Epelman M, et al. Role of color Doppler sonography and renal function tests in the evaluation of Budd-Chiari syndrome. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1993;161(2):377-381.

19. Schelzig H, Thelen S, Rehders TC, et al. Surgical management of leiomyosarcoma of the inferior vena cava: results of a multicenter study. Ann Surg. 2020;271(3):567-575.

20. Lenz CJ, Krutman M, Tseng JF, et al. Multidisciplinary surgical treatment of tumors involving the inferior vena cava. Ann Surg Oncol. 2018;25(11):3401-3410.

21. Wang S, Zhao W, Ding J, et al. Oncovascular surgical approach for inferior vena cava tumors. J Vasc Surg. 2019;69(1):130-139.

22. Wong HH, Karam SD, Schmid RA, et al. Surgical management of primary and secondary tumors of the inferior vena cava. Ann Thorac Surg. 2015;100(1):331-337.

23. Yao X, Xiao Y, Ma K, et al. Venous reconstruction with autologous femoral vein graft after resection of inferior vena cava leiomyosarcoma. Ann Vasc Surg. 2019;60:364.e15-364.e18.

24. Goltz JP, Lehnert T, Kröger JR, et al. MR imaging of inferior vena cava leiomyosarcoma: report of 13 cases. Eur Radiol. 2010;20(9):2221-2228.