Chronic venous disease during pregnancy

2. 136, boulevard Haussmann 75008 Paris, France

Abstract

Pregnancy plays an important role in the onset and development of chronic venous disease in women. Changes to the venous system that occur during pregnancy are linked to hormonal secretions, as well as compression of the iliac veins by the gravid uterus. The clinical signs are varied and can be distressing. The reasons that pregnant women consult can be grouped under the terms aesthetic, preventative, and therapeutic. Treatment is essentially noninterventional based on: (i) the wearing of medical compression stockings, adapted to the severity of the venous disease; (ii) sufficient elevation of the lower limbs when in the supine position; and (iii) the prescription of venoactive agents in case of symptoms.

Introduction

Chronic venous disease (CVD) refers to a group of disorders associated with the dysfunction of one or more of the 3 lower extremity venous systems: superficial, deep, or perforating.1-3 CVD affecting the superficial venous system results in the appearance of 3 clinical signs: telangiectasia and venulectasia, classified as C1 in the C class of the CEAP classification; and varicose veins, classified as C2. These signs are often associated with classical venous symptomatology, although this association has never been proven.4 Other signs of an impaired venous system include edema (C3), trophic skin disorders (C4a and C4b), and leg ulcers (healed C5 and open C6).1 The appearance and progression of CVD often occurs during pregnancy.5 Women frequently consult early in pregnancy to find out about the risks, complications, and treatment options.

Pathophysiology

Pregnancy results in numerous adaptations to the circulatory system.5-12 CVD during pregnancy is caused by a combination of two main mechanisms: (i) an increase in venous pressure of the lower limbs due to compression of the inferior vena cava and iliac veins by the gravid uterus; and (ii) an increase in venous distensibility due to the effect of hormonal mediators. There is a linear increase in lower limb venous pressure from the beginning to the end of pregnancy. By the end of pregnancy, the femoral venous pressure in the supine position is increased threefold.6

The increase in venous distensibility occurs from the first months of pregnancy and affects leg and arm veins in the same manner. The placenta secretes a large quantity of steroid hormones from the sixth week of pregnancy. Oestradiol and progesterone may have a vasodilating action, which would contribute to the increasing diameter of the veins observed throughout pregnancy, and the significant decrease that occurs after childbirth.8,9 They do not, however, exactly return to their initial diameter, particularly in patients with a history of varicose veins.5,8,10,12 Knowledge of this pathophysiology explains the rate of occurrence and development of CVD during pregnancy. It also explains the therapeutic effectiveness of medical compression stockings.

Clinical Epidemiology

Approximately 15% of pregnant women present with varicose veins, which mostly occur at the beginning of the second trimester.13 Age, gender, and a family history of CVD increases the risk of occurrence of varicose veins during pregnancy. 12 The relative risk of varicose veins increases 4-fold in women over 35 years of age compared with those under 29 years of age. The risk is also increased twofold in multiparous women compared with those in their first pregnancy.5 If hereditary risk factors are present, the relative risk increases 6.2-fold. The prevalence of varicose veins in women over 40 years of age is as follows: 20% in nulliparous women, 40% in women who have had 1 to 4 pregnancies, and 65% in women who have had 5 or more pregnancies.14 In addition, correlations have been found between the number of varicosities affecting the greater and smaller saphenous veins, the size of the varicosities, and the number of pregnancies.12,13

Clinical Assessment

The objectives of the first assessment are to:

1. Determine the reasons for consultation by analysis of the questionnaire given to the patient prior to the visit.15,16

2. Capture on a pre-prepared document (which will be included in the dossier) what the patient sees and feels. This will allow future comparisons to be made.1,2,17

3. Prepare a medical record, which will include findings from the medical examination (diagram of the lower limbs).

The examination will provide information on the reason for consultation. The most common reason is the onset of physical signs and sometimes symptoms. Knowing whether or not these existed before the pregnancy is important as it gives a good indication of the progression of the condition. The examination will also confirm the stage of pregnancy and the expected delivery date.

Symptoms vary widely, from nonexistent to severe or unexpected. Pain (phlebalgia) and the sensation of edema are frequent. They often occur at the end of the day and are increased by heat, advancing pregnancy, and professional activities.17

Signs are also variable and often related to a personal and family history of CVD.

Telangiectasia and venulectasia are more dense and larger than in nonpregnant women. Varicose veins are extremely diverse. They can range from small isolated dilatations to very impressive varices “pseudo-angiomas” (Figure 1, Figure 2).

Figure 1. Large varicose vein parallel to the path of the greater

saphenous vein and telangiectasia; appeared in the fourth

month of pregnancy. Note the likely perforating vein. (C1 and

C2 of the CEAP classification) (Photo ACT).

Figure 2. Wooden reference dowels to illustrate the diameter

(mm) of varicose veins. Allows physicians to determine the

diameter of a palpable varicose vein in comparison with a

reference standard (Photo ACT).

The dilatations can affect isolated veins or simultaneously affect each element of the superficial venous network: greater and smaller saphenous veins, their collaterals, and perforating veins. They can also involve one or both lower limbs. The distribution is relatively homogeneous with approximately one-third of women having the right leg affected, one third the left, and one third a bilateral distribution.6,13

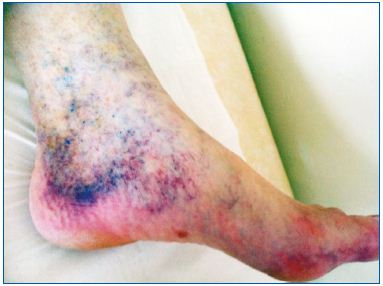

In order to follow the progression of these varicose veins, it is necessary to make a note of the maximum diameter of each leg. This record is a method for scoring the clinical severity of the varicose veins.18 Vulvar and perineal varicose veins exist in about 10% of cases.13 They are often reported by women worried about a risk of rupture (Figure 3). They are not generally painful, but can become so when their volume becomes important.14,19

Figure 4. A classic corona phlebectatica Van der Molen has

been described as being composed of numerous telangiectasia

grouped together at the edges.

Complications are mainly cutaneous (skin changes or subcutaneous tissue), but these are rare given the young age of these women, the short period of progression of the condition, and improved treatment options in recent years. Any trauma to an edematous leg may, however, lead to a chronic wound. Such ulcers (C6) are more likely to occur if there is a precursor: corona phlebectatica (Figure 4).20 The appearance of either of these two signs requires the immediate initiation of treatment with medical compression therapy, preferably in combination with a venotonic agent. Thrombotic complications in the superficial and deep venous systems are a major concern in pregnant women, in whom the risk of venous thromboembolism is four times higher than in nonpregnant women of the same age. Assessment of this risk should form part of the clinical examination.21 Prevention of thromboembolic risk and antithrombotic treatment should be adapted on an individual basis.22-24

After childbirth, C1 and C2 diminish rapidly, but often incompletely. 25 C3-C6, if present, improves gradually, pelvic compressions are no longer an issue. A final assessment of the regression is only made 3 months after childbirth or after stopping breastfeeding.7,14

Venous Echo-Doppler Examination

Every consultation during the first months of pregnancy should include a venous Doppler examination of the lower limbs. This initial assessment of the lesions may be supplemented by a more detailed patient history including details of CVD events: pelvic veins (ovarian and uterine veins), abdominal veins, and laboratory tests.25,26

After the clinical examination, which will help guide treatment and determine the maximum diameters of affected veins, doctors should:

- Assess the venous networks of the affected limb as well as the contralateral limb, taking care not to let the woman stand for too long to avoid any discomfort.

- Record all findings on an initial illustration so that changes can be followed with each advancing stage of pregnancy.

Treatment

The treatment should, in order of priority: (i) reassure the patient; (ii) relieve symptoms; (iii) reduce or stop progression of the disease; and (iv) prevent complications.

Prevention counseling for lifestyle modification

Reassure. Worried patients should be reassured, explaining that most varices will diminish after childbirth and that complications are rare if treatment is followed.

Advise rest. During the day, extended rest periods are beneficial. We suggest 15 minutes of rest for every hour a patient spends on their feet. At night, the foot of the bed (and not the head) should be raised. A question often asked is “How high?” We propose the following rule: raise 1 cm for each hour a patient spends on their feet during the day (eg, 10 hours standing=10 cm elevation).25,27 Note: there should be no cushion under the heels and nothing at the end of the mattress.

Exercise. Physical exercises that boost muscle power of the lower limbs and are compatible with pregnancy should be practiced as often as possible (walking, swimming, yoga, gentle gymnastics).13

Compression therapy

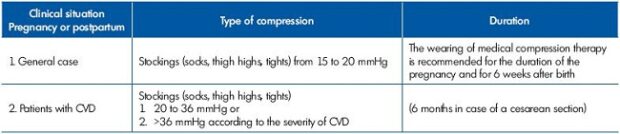

The French National Authority for Health (La Haute Autorité de Santé en France, www.has-sante.fr) has produced special recommendations for compression therapy during pregnancy (Table I). These serve as a useful starting point. Our goal is to improve them based on the experience we have gained in daily practice.

Table I. Compression therapy for the prevention of venous thrombosis during pregnancy and postpartum (from a document published by the French National Authority for Health (La Haute Autorité de Santé en France, HAS)

Some simple rules to follow:

1. Compression therapy should be prescribed at the appearance of the first venous disorder or at the start of pregnancy in case of preexisting CVD.28-30

2. It must be continued throughout pregnancy and the physician’s role should be to convince their patients of this, “to convince, we must be convincing, therefore convinced!” Continuing compression therapy for 9 months to 1 year is acceptable given the benefits that can be achieved.

3. Regardless of the material used, multilayer bandages are a very good therapeutic solution: two bandages (or three) one over the other form a very good bandage. The same effect is achieved with two (or three) medical compression stockings (Figure 5).31

4. In general, the pressures used will be higher with more pronounced signs and symptoms and with more advanced stages of pregnancy.

Figure 5. Two layered medical compression stockings. The fabric

of the two stockings is identical so that the outer stocking slips

easily over the under stocking. In this photo, two knee-high

stockings are worn one on top of the other.

Medical compression stockings

Above-knee stay-up compression stockings are the most frequently prescribed due to their greater acceptability during pregnancy: no abdominal discomfort, relatively easy to put on, effects felt immediately (hence the need to have some samples to hand to patients). In case of an allergic reaction to the stay-up band, stockings with a band of anti-allergenic nonslip grips should be prescribed. Maternity tights (extendable waist) or socks (more comfortable and less constraining) may also be prescribed depending on patient preference. Indeed, there is no difference in efficacy between the different types of stocking (socks, above-knee stockings, or tights). The compression stocking material is important to consider. The choice of stocking will be based on its tolerance, comfort, and patient preference.

Compression force

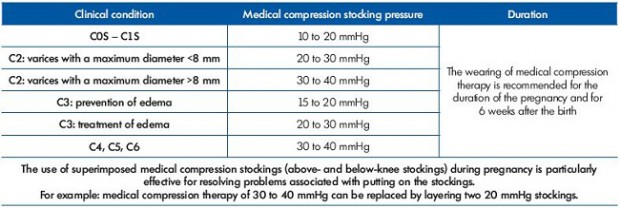

Whether indicated by class of compression or by mmHg (International Unit), the compression force will be adapted to the severity of CVD and to patient acceptance (Table II).28

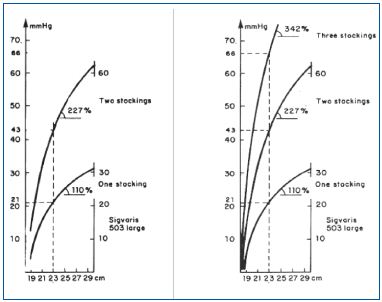

Note: a compression stocking exerting a pressure of 40 to 45 mmHg will reduce the diameter of the varicose vein by half. A minimum of 90 mmHg pressure is required for venous reflux to disappear and the diameter of the vein to return to normal.32,33 A high pressure can always be obtained by layering compression stockings. Appliances exist that facilitate the application of elastic stockings at high pressure, such as the Extensor or Butler stocking aids.34

Layering

The layering of compression stockings can be particularly useful during pregnancy. When layered, the pressure of the stockings is additive,31 similar to the number of revolutions when a bandage is used to apply pressure. For example, a compression stocking exerting a pressure of 30 to 40 mmHg can be replaced by layering two compression stockings of 20 mmHg (Figure 6).35

Figure 6. Hysteresis curves for one, two, and three layered

medical compression stockings. The pressures are additive. One

medical compression stocking on an ankle with a perimeter of

23 cm gives a pressure of ±20 mmHg; two stockings provide a

pressure of ±42 mmHg, and a third stocking raises the pressure

to ±66 mmHg.

This technique reduces the effort required in applying and adjusting the force of compression. The top compression stocking is simply put on or removed by the patient to adjust the force of compression: stronger or weaker depending on their activities. In addition, as pregnancy advances, fitting compression therapy becomes more and more difficult due to the increased volume of the abdomen. This difficulty is increased when applying high pressure compression stockings. Layering of the stockings therefore can be particularly useful.

In the case of a localized painful varice (often associated with an incompetent perforating vein), a localized circular compression (ie, using an adhesive bandage) applied under the stocking produces effective relief.

Compression therapy is often very well accepted during pregnancy as the duration is short. The women clearly and rapidly feel the efficacy. In addition, they welcome the opportunity to conceal unsightly lesions.36

After childbirth

Compression therapy still has its place, but should be adapted to changes in the level of CVD.

Venoactive agents

The use of venoactive agents is very useful for treating symptoms.37 The duration of their use will depend on their tolerability and the preference of the patient. Their efficacy is known and recognized, but it is a function of their chemical characteristics and dosing. It should be noted that in the updated guidelines on the management of chronic venous disorders, the recommendation for the micronized purified flavonoid fraction (MPFF) is strong, based on benefits that clearly outweigh the risks and evidence of moderate quality (grade 1B).37

The duration of treatment is between 1 and 3 months, but can be repeated in case of a recurrence of symptoms on discontinuation of treatment. The manufacturers do not recommend taking venoactive agents while breast feeding.

Special case: treatment of vulvar varicose veins38

Treatment is only considered if there are associated symptoms: pain, feeling of heaviness, burning. In this case, we advise the application of a gel or cooling the lesions with reusable thermal pads (ie, the ColdHot 3M® device). An abdominal pregnancy support belt can also be of use. Wearing a sanitary towel can also strengthen the local compressive effect. The objective is to reduce the pressure inside the vulvar varicose veins.

Is sclerotherapy possible during pregnancy?

No causal relationship between the use of sclerotherapy and an adverse effect on either mother or child has been determined. However, there are no well-established clinical data on the use of sclerotherapy during pregnancy and lactation. For the authors, sclerotherapy is contraindicated during pregnancy and lactation. The European guidelines consider sclerotherapy as a relative contraindication (Individual benefit-risk assessment mandatory).13

Summary

The two fundamental treatments are: daytime medical compression therapy and nighttime elevation of the lower limbs.

Four points to remember:

1. Always consider the complaints of a woman at the beginning of a pregnancy: preventative action is likely to slow down or even stop the progression of venous disease!

2. The presence of varicose veins early in pregnancy, even of small diameter, must lead to implementation of the two fundamental treatments.

3. Without exception, no sclerotherapy during pregnancy.

4. Do not let a pregnant woman believe that nothing can be done for her legs: the combination of compression and elevation is a simple and very effective therapy!

Action to be taken in women who want to become pregnant

Opinions differ concerning what should be recommended to women wishing to become pregnant. Two situations are possible: there are no visible signs (C0a of the CEAP classification) or signs are present!

− No signs are evident. Advise patients to consult a specialist in the event that venous symptoms or signs characteristic of CVD appear.39

− Signs of CVD are present:

Moderate signs: previously prescribed treatment should be continued during pregnancy. Treatment should be increased if new signs or symptoms appear, or if existing signs or symptoms worsen.

Signs are important, such as dilatation of a varicose vein or edema: treatment as above including medical compression therapy, but interventional therapy may also be proposed. Pregnancy may damage the venous networks, but to what extent, and in what form?

“If the patient has had major treatment before pregnancy (for example, sclerotherapy or surgery in combination with medical compression), the varicose network will have mostly regressed; the maximum diameter will have become very small. Pregnancy will not make this reappear, especially if preventative medical compression stockings (30 to 40 mm Hg) are worn.”

“Conversely, if there was no curative treatment before the pregnancy and if the objective is to stop progression, almost mandatory for varicose disease, it will be necessary to wear 30 to 40 mm Hg compression stockings during the pregnancy! This becomes all the more important if there is a major risk of thrombosis or if the woman has experienced venous problems during a previous pregnancy.”22

Conclusion

Always take into consideration women’s concerns about their lower limbs in early pregnancy and do not let them believe that nothing can be done. Appropriate treatment is likely to slow down or even stop CVD progression. The presence of even moderate symptoms or signs of CVD in early pregnancy should lead to implementation of two fundamental treatments: daytime medical compression therapy and nighttime elevation of the lower limbs. Venoactive agents should be offered if patients are symptomatic. The combination of “daytime compression and nighttime elevation” of the lower limbs is a simple, “ecologic,” and particularly effective treatment. It is up to us as physicians to convince people that it is possible to eradicate this condition.

1. Eklöf B, Rutherford RB, Bergan JJ, et al; American Venous Forum International Ad Hoc Committee for Revision of the CEAP Classification. Revision of the CEAP classification for chronic venous disorders: consensus statement. J Vasc Surg. 2004;40:1248-1252.

2. Perrin M. La classification CEAP. Analyse critique en 2010. Phlébologie. 2010;4.

3. Uhl JF, Gillot C. Embryology and threedimensional anatomy of the superficial venous system of the lower limbs. Phlebology. 2007;22:194-206.

4. Bradbury A, Evans CJ, Allan P, Lee AJ, Ruckley CV, Fowkes FG. The relationship between lower limbs symptoms and superficial and deep venous reflux on duplex sonography: The Edinburgh Vein Study. J Vasc Surg. 2000;32:921-931.

5. Sparey C, Haddad N, Sissons G, Rosser S, de Cossart L. The effect of pregnancy on the lower-limb venous system of women with varicose veins. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 1999;18:294-299.

6. Summer DS. Venous dynamics-varicosities. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1981;24:743-60.

7. Skudder PA, Farrington DT . Venous conditions associated with pregnancy. Semin Dermatol. 1993;12:72-77.

8. Cordts PR. Anatomic and physiologic changes in lower extremity venous hemodynamics associated with pregnancy. J Vasc Surg. 1996;5:763-767.

9. Calderwood CJ, Jamieson R, Greer IA. Gestational related changes in the deep venous system of the lower limb on light reflexion rheography in pregnancy and the puerperium. Clin Radiol. 2007;62:1174-1179.

10. Pemble L. Reversibility of pregnancyinduced changes in the superficial veins of the lower extremities. Phlebology. 2007;22:60-64.

11. Marpeau L. Adaptation de l’organisme maternel à la grossesse. Traité d’obstétrique. Elsevier Masson. 2010:24- 28.

12. Cornu-Thenard A, Boivin P, Baud JM, De Vincenzi I, Carpentier PH. Importance of the familial factor in varicose disease. Clinical Study of 134 families. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1994;20:318-326.

13. Rabe E. Breu FX, Cavezzi A, et al; the Guideline Group. European guidelines for sclerotherapy in chronic venous disorders. Phlebology. 2013;doi:10.1177/0268355 513483280.

14. Prior IA, Evans JG, Morrison RB, Rose BS. The Carterton study. 6. Patterns of vascular, respiratory, rheumatic and related abnormalities in a sample of New Zealand European adults. N Z Med J. 1970;72:169-177.

15. Antignani PL, Cornu-Thénard A, Allegra C, Carpentier PH, Partsch H, Uhl JF; European Working Group on Venous Classification under the Auspices of the International Union of Phlebology. Results of a questionnaire regarding improvement of C of CEAP. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2004;28:177-181.

16. Uhl JF, Cornu-Thenard A, Antignani PL, et al. Importance du motif de consultation en phlébologie: attention à l’arbre qui cache la foret! Phlébologie. 2006;59:47-51.

17. Ponnapula P, Boberg JS. Lower extremity changes experienced during pregnancy. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2010;49:452-458.

18. Cornu-Thenard A, Maraval M, De Vincenzi I. Evaluation of different systems for clinical quantification of varicose veins. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1991;17:345-348.

19. Dodd H, Payling Wrigh. Vulval varicose veins in pregnancy. Br Med J. 1959;28:831-832.

20. Uhl JF, Cornu-Thenard A, Satger B, Carpentier PH. Clinical analysis of the corona phlebectatica. J Vasc Surg. 2012;55:150-153.

21. Cazaubon M, Elalamy. Epidémiologie du risque veineux thrombo-embolique pendant la grossesse. Angéiologie. 2011;1:5-8.

22. Biron-Andréani C. Venous thromboembolic risk in postpartum. Phlebolymphology. 2013;20:167-173.

23. Bates SM, Greer IA, Pabinger I, Sofaer S, Hirsh J; American College of Chest Physicians. Venous thromboembolism, thrombophilia, anti-thrombotic therapy and pregnancy: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2008;133:844S-886S.

24. Guyatt GH, Akl EA, Crowther M, Gutterman DD, Schuünemann HJ; American College of Chest Physicians Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis Panel. Executive summary: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2012;141:7S-47S.

25. Boivin P, Cornu-Thenard A, Charpak Y. Pregnancy-induced changes in lower extremity superficial veins: an ultrasound scan study. J Vasc Surg. 2000;32:570-574.

26. De Maeseneer M, Pichot O, Cavezzi A, et al; Union Internationale de Phlebologie. Duplex ultrasound investigation of the veins of the lower limbs after treatment for varicose veins – UIP consensus document. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2011;42:89- 102.

27. Cornu-Thenard A. Prévention de la Maladie Variqueuse chez la Femme enceinte. Angéiologie. 2000;2:82.

28. Partsch H, Flour M, Smith PC; International Compression Club. Indications for compression therapy in venous and lymphatic disease consensus based on experimental data and scientific evidence. Under the auspices of the IUP. Int Angiol. 2008;27:193-219.

29. Benigni JP, Gobin JP, Uhl JF, et al. Utilisation quotidienne des bas médicaux de compression. Recommandations cliniques de la Société Française de Phlébologie. Phlébologie. 2009;62:95- 102.

30. HAS et groupe de réflexion. 2011. www. has-sante.fr

31. Cornu-Thenard A, Boivin P, Carpentier PH, Courtet F, Ngo P. Superimposed elastic stockings: pressure measurements. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33:269-275.

32. Partsch B, Partsch H. Calf compression pressure required to achieve venous closure from supine to standing position. J Vasc Surg. 2005;42:734-738.

33. Cornu-Thenard A, Benigni JP, Uhl JF. Hemodynamic effects of medical compression stockings in varicose veins: clinical report. Acta Phlebologica. 2012;13:19-23.

34. Cornu-Thenard A, Flour M; Malouf M. Compression Treatment for Chronic Venous Insufficiency, Current Evidence of Efficacy. In: Mayo Clinic Vascular Symposium 2011. Minerva Medica Torino. 2011. Ed. Peter Gloviczki, 413-419.

35. Cornu-Thenard A. Réduction d’un oedème veineux par bas élastiques, uniques ou superposés. Phlébologie 1985;38:159- 168

36. Thaler E, Huch R, Huch A, Zimmermann R. Compression stockings prophylaxis of emergent varicose veins in pregnancy: a prospective randomized controlled study. Swiss Med Wkly. 2001;131:659-662.

37. Nicolaides A, Kakkos S, Eklof B, et al. Management of Chronic Venous Disorders of the Lower Limbs. Guidelines According to Scientific Evidence. Int Angiol. 2014. In press

38. Van Cleef JF. Treatment of vulvar and perineal varicose veins. Phlebolymphology. 2011;18:38-43.

39. Carpentier PH, Poulain C, Fabry R, Chleir F, Guias B, Bettarel-Binon C; Venous Working Group of the Société Française de Médecine Vasculaire. Ascribing leg symptoms to chronic venous disorders: the construction of a diagnostic score. J Vasc Surg. 2007;46,991-996.