CLINICAL CASE 2. The natural history of varicose vein progression

Matthieu Josnin, MD, PhD

St Charles Clinic,

Department of Vascular Medicine

Interventional Phlebology Unit

Wound Care Center,

La Roche-sur-Yon, France

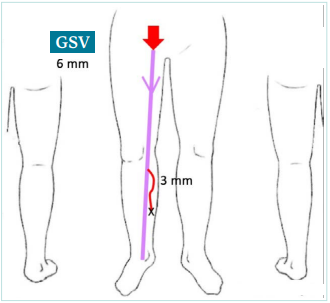

This is an evolving clinical case in a patient first presenting at the age of 20, followed through the age of 75. We will start with the first consultation where the patient, aged 20 years, consulted you for the first time with the main reason being occasional discomfort along the inner side of the right lower limb during prolonged standing, especially in summer. The patient had no children, no particular history apart from a family history of chronic venous disease (CVD) affecting both her parents, and she was on hormonal contraception. Further questioning revealed that these complaints dated back to her 12th birthday and had been attributed to growth by her parents and her family doctor. Clinically, the patient was free of skin changes, and a visible varicose tributary was found on her leg. The examination resulted in the following mapping: clinical, etiological, anatomical, pathophysiological (CEAP) classification C2sEpAs2,3,5Pr (Figure 1).

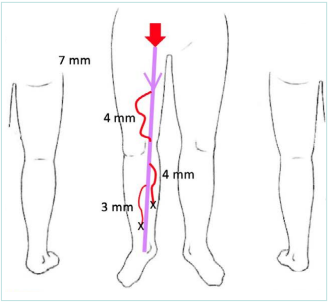

This patient consulted you again at the age of 35 years old. She had not been treated for her varicose veins, and she had 2 pregnancies that were carried to term but with symptoms that have deteriorated. The vein diameters had increased in the great saphenous vein (GSV) (+1 mm) and the tributaries, which became more numerous and dilated. She had ankle edema. She wished to have a third child and asked for your advice on treating her GSV. You performed an ultrasound examination, resulting in the following mapping: C3sEpAs2,3,5Pr (Figure 2).

Finally, it was decided not to treat this patient. She had been offered endovenous laser ablation therapy with ultrasound-guided foam sclerotherapy of her tributaries, but due to family reasons, she did not return for intervention. She was advised to wear compression stockings as regularly as possible and to continue taking venoactive drugs, especially since the edema reinforced her indication.

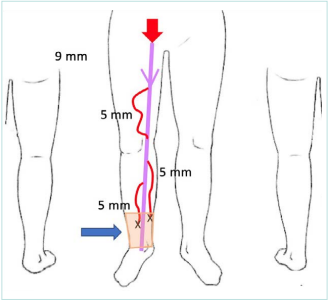

Finally, time passed. The patient, now 75 years old, returned to consult you with painful inflammatory dermatitis of the right ankle (Figure 3) and permanent ankle and leg edema. She is being treated for atrial fibrillation with rivaroxaban 20 mg once daily.

Your examination found a GSV insufficiency with a diameter of 9 mm and tributaries of 5 mm that are going to the area of inflammatory and pigmented dermatitis. Her CEAP classification is C3,4asEpAs2,3,5Pr (Figure 3).

Figure 1. The patient at the age of 20 years old. A schematic showing incompetent right great saphenous vein (GSV) of 6 mm at the thigh level and a varicose tributary of 3 mm at the calf level.

Figure 2. The patient at the age of 35 years old. A schematic showing incompetent right great saphenous vein (GSV) of 7 mm at the thigh level and varicose tributaries of 3-4 mm at the thigh and calf levels.

Figure 3. The patient at the age of 75 years old. A schematic showing incompetent right great saphenous vein (GSV) of 9 mm at the thigh level, multiple varicose tributaries of 5 mm at the thigh and calf levels, and zone of dermatitis at the ankle.

Discussion

Dr Geroulakos. Risk factors for the progression of varicose veins include advanced age, obesity, sedentary lifestyles, occupation, family history, and pregnancy. Varicose veins are associated with vein wall inflammation; however, the precise etiology of the inflammation is unclear. When varicose veins develop, these can progress through cycles of inflammation and leukocyte recruitment, leading to further deterioration of vein walls and valves, increased hypertension, and the release of additional proinflammatory mediators. Early treatment of symptomatic varicose veins and lifestyle changes can help break the inflammatory cycle and improve symptoms.

Dr Kan. Sometimes, we feel that women are more prone to have varicose vein symptoms than men. In fact, varicose veins are almost as common in women as in men, but spider veins are more common in women. Varicose veins may be completely asymptomatic and cause no health problems. Based on findings from the Edinburgh Vein Study, a population-based cohort study, we know that over 13 years, nearly half of the general population with chronic venous disease (CVD) worsened, and almost a third of those with varicose veins developed chronic venous insufficiency (CVI) skin changes, with an increase in their risk of ulcer disease. The annual progression rate is 4.3%. In nearly half of the patients with exacerbations, the disease progressed in one leg (affecting both as well), whereas in one-third of cases, it progressed in both legs; and in one-fifth of cases, unilateral disease progressed to bilateral disease, but the original diseased leg did not deteriorate. Age, family history of varicose veins, history of deep venous thrombosis (DVT), overweight, and superficial or deep reflux may affect the risk of progression. A family history of varicose veins and a history of DVT were the only 2 baseline factors independently associated with an increased risk of progression.1

Dr Nikolov. The data suggest reflux progression may develop from segmental to multisegmental superficial reflux. At younger ages, reflux in tributaries and nonsaphenous veins is more frequent. During a 13.4-year follow-up period, 57.8% (4.3%/year) of all CVD patients showed progression of the disease.1 Annual progression rates of approximately 4% have been reported for the Edinburgh Vein Study, the Bonn Vein Study, and reviews of other epidemiological studies. In the Edinburgh Vein Study, the overall progression rate was 58% after a follow-up of 13 years. The main risk factors for progression in patients with varicose veins at baseline were age over 55 years (odds ratio [OR], 3.9; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.1–14.3), overweight/obesity (body mass index [BMI], ≥25; OR, 1.9; 95% CI, 1.1–3.1), and a family history of varicose veins (OR, 1.9; 95% CI, 1.20–3.04). Additional risk factors included female sex and superficial venous reflux.2,3

Dr Tazi Mezalek. Nearly half of the general population with CVD deteriorated during 13 years, and almost one-third with varicose veins developed skin changes of CVI, increasing their risk of ulceration.1 A randomized controlled trial (RCT) called the REACTIV trial (Randomised and Economic Assessment of Conservative and Therapeutic Interventions for Varicose Veins) confirmed that patients randomized to the best medical treatment (graduated compression stockings) had a worse quality of life (QOL) after 2 years than patients randomized to the interventional (sclerotherapy, open surgery) treatment of their varicose veins.4 The risk of progression might be influenced by age, family history of varicose veins, history of DVT, overweight, and superficial reflux, especially in the small saphenous vein and with deep reflux.

Dr Lobastov. There is conflicting evidence on the prevalence of CVD, CVI, and varicose veins in men and women. According to a recent meta-analysis, women are at higher risk of developing CEAP (clinical, etiological, anatomical, pathophysiological classification system) clinical classes C1-2 (OR, 1.58; 95% CI, 1.53-1.62) and C1-6 (OR, 2.26; 95% CI, 2.16-2.36), but not C4-6 (OR, 1.02; 95% CI, 0.97-1.08).5 The main problems of such assessment are that women more often seek medical care for early-stage CVD (C0-1), and the difference between reticular and varicose veins is not always correctly reported, especially in early epidemiological studies. Parity was suggested as an essential risk factor for the development of CVD, with a positive correlation between the number of pregnancies and the prevalence of C1-2 clinical classes.5-7 However, fewer studies stated the absence of such a correlation.8-10 The confounding role of age and ethnicity may be the reason for this inconsistency. The evidence on hormonal contraception is more conflicting with a similar number of studies that find differences or do not.5

The progression of CVD is studied better in prospective trials. Combining their results, the annular progression rate may be estimated as 6% to 24% for the detection of new reflux on previously intact venous segments, 24% for the appearance of new varicose veins, 4% to 5% for the progression of C2 to higher clinical classes, 5% for the development of new skin changes, 1% to 1.4% for new ulceration, 1% to 2.9% for superficial vein thrombosis, and 1.4% for bleeding.11-16 All these figures advocate the treatment of varicose veins at early stages to prevent further progression and complications.

Dr Josnin. The practitioner who sees a young patient with varicose veins must keep in mind that, unlike a man, she may have pregnancies, that she will probably be on the contraceptive pill, and that this, in case of evolution of her venous disease, will expose her to the risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE). Prevention must take precedence over treatment if it is not immediately necessary, regardless of the patient’s sex. However, wearing compression stockings throughout pregnancy will be imperative for this patient if she has not taken care of her varicose veins and if they have evolved. It is also important not to rely on being able to foresee the evolution of the disease to recommend that the patient return for another visit and to give advice about what should lead the patient to seek consultation (eg, an increase in the symptoms, increase in the size of the varicose veins, skin changes).

Dr Geroulakos. If the QOL is affected by symptomatic varicose veins, then endovenous thermal ablation with phlebectomy under local anesthesia should be considered.

Dr Kan. Most varicose veins in young, nulliparous women do not have severe symptoms. Even those valvular varicose veins alone or as part of pelvic congestion syndrome (PCS) are rare. In adolescent patients with severe symptoms, a comprehensive clinical examination, duplex ultrasound (DUS), contrast venography, and magnetic resonance venography (MRV) should be performed to rule out other diagnoses. Imaging results confirmed the presence of large venous lakes. Note the venous drainage to the internal iliac vein and connection to the great saphenous vein (GSV). Attention also should be paid to ovarian or internal iliac veins or their major tributaries for insufficiency, dilation, or reflux. Since no obvious symptoms exist, most patients do not require any intervention during this period. Two major factors guiding intervention decisions or not are symptoms and their association with PCS or leg varicose veins. Designing a treatment plan is important for any venous circulation disorder that has been identified by imaging. Advanced imaging of the pelvic and leg veins should be obtained to guide treatment, including compression, sclerotherapy, embolization, or surgical ligation.

Dr Lobastov. Considering the risk of CVD progression, endovenous ablation may be offered for adult women of any age. The most effective approach is EVLT or radiofrequencyablation (RFA) of the GSV trunk.17 At the same time, isolated ablation of varicose tributaries with mini-phlebectomy or sclerotherapy with preservation of the GSV trunk may be an option at the early stages of CVD, considering a small diameter of the vein.18,19 In terms of GSV preservation, a hemodynamic approach with classical open or endovascular CHIVA (Conservatrice et Hemodynamique de l’Insuffisance Veineuse en Ambulatoire [Conservative and Hemodynamic treatment of Venous Insufficiency in outpatients]) may be discussed as having the lowest rate of recurrence.20,21 According to the continuous use of estrogen-containing oral contraceptives, no good evidence of the safety of endovenous ablation is available. The recent consensus on sclerotherapy suggests individual assessment of VTE risk, making a decision for estrogen cessation case by case, and avoiding intervention in women at high VTE risk and known thrombophilia.22

Dr Dzhenina. A woman’s QOL can be the starting point for deciding on surgery. Suppose existing varicose veins reduce the QOL due to venous symptoms or a cosmetic defect. In that case, neither the patient’s young age nor the absence of previous pregnancies should deny the intervention. In addition, long-term use of hormonal contraceptives may affect the progression of CVD.23 Moreover, using oral contraceptives in the background of varicose veins may be associated with an increased risk of VTE by 2 to 6 times for DVT and 1.4 to 5.6 times for superficial venous thrombosis (SVT).24

When planning endovenous ablation or open surgery, it should be taken into account that estrogen-containing contraceptives (not only oral pills but also vaginal rings and transdermal systems) are considered an independent VTE risk factor. According to the World Health Organization (WHO) eligibility criteria for hormonal contraceptive use, minor surgery does not require cessation of hormonal contraception.25 However, there is currently no evidence of the safety of endovenous ablation in the background of contraceptive pills. It seems appropriate to assess the global VTE risk, considering use of hormonal contraceptives. The essential issue is that early discontinuation of oral contraceptives (as indicated for major surgery by WHO) is associated with a high risk of adverse events. After the resumption of treatment, the risk of VTE increases dramatically, as in the case of first usage (“the new user effect”).26,27 So, the risk of postoperative VTE in such patients combines the effect of intervention by itself and the “new user effect” if hormonal contraceptives were stopped before surgery and resumed after it. Regarding these facts, it seems safer and more comfortable for women not to stop hormonal contraceptives before endovenous ablation but to use pharmacological prophylaxis of VTE according to the individual risk. The assessment should consider contraceptive pill usage. That’s why the Caprini score looks most appropriate.28

Dr Josnin. The treatment chosen was the wearing of compression stockings and taking VAD, particularly during flare-ups and in the summer period, as recommended because of her symptoms. These recommendations have prevailed since 2008 and were recently updated by the European Society of Vascular Surgery, which suggests this course of action with grade IIA: “For patients with symptomatic CVD, who are not undergoing interventional treatment, are awaiting intervention, or have persisting symptoms and/ or edema after the intervention, medical treatment with venoactive drugs (VADs) should be considered to reduce venous symptoms and edema, based on the available evidence for each individual drug.”29-32

The issues that may arise for the practitioner in deciding whether to remove the GSV are that the patient has never had a child, the symptoms are not very marked, and she is young. These arguments are, however, to be discussed as they have long prevailed. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommendations regarding the diagnosis and management of varicose veins insist on one point. However, they stipulate that they do not cover the spectrum of the child.33

Dr Geroulakos. Pregnancy is considered a major risk factor in women’s increased incidence of varicose veins, leading to venous reflux and leg edema. The most common symptom of varicose veins and edema is the substantial pain experienced, as well as night cramps, numbness, tingling, and legs that may feel heavy and achy. Other complications include thrombophlebitis and bleeding.

Dr Kan. Pregnancy is thought to be a major contributing factor to the increased incidence of varicose veins in women, which can lead to venous insufficiency and leg edema. The proposed mechanism for pregnancy-induced varicose veins is that the gravid uterus causes compression of the pelvic venous system, resulting in lower-extremity venous hypertension coupled with hormonal changes that lead to increased venous distensibility. Increased parity, excessive gestational weight gain, post-term pregnancy, and preeclampsia affect the development of varicose veins after pregnancy. The most common symptoms of varicose veins and edema are severe pain, nighttime cramping, numbness, tingling, and legs that may feel heavy, sore, and possibly considered unsightly.7

Vulvar varicosities, ie, dilated venous channels in the vulvar area, are rare and almost exclusively affect women during pregnancy, but most do not report any symptoms. Nearly 4% to 22% of pregnant women present with vulvar varicosities. Most cases disappear immediately after labor or postpartum, and only 4% to 8% persist or worsen with time. Sometimes, a patient might have complication of hemorrhoids with pain, itching, and bleeding. Varicose veins can be associated with an increased risk of VTE during pregnancy. Most untreated varicose veins in pregnancy are usually harmless and get better after the baby is born, and most don’t need treatment. Also, hemorrhoids are typically benign and may get better after the baby is born.

Dr Lobastov. Despite pregnancy being an established risk factor for varicose veins and CVD, no clear evidence exists on the disease progression and development of complications.

Dr Dzhenina. Pregnancy is a significant risk factor for CVD development in women. In addition to mechanical factors such as compression of pelvic veins by the pregnant uterus and an increase in the circulating blood volume, hormonal changes play a pivotal role. Progesterone negatively affects the collagen and elastin network of the venous wall, contributing to the dilatation of vessels. Parity, short intervals between pregnancies, and leg pain during premenstrual syndrome are the predictors of varicose veins and CVD development in pregnancy.34-36

The dilation and tortuosity of superficial veins observed during pregnancy in some women may spontaneously reduce postpartum. But there are no rules to distinguish between physiological changes and CVD development in pregnant women.

When pregnancy occurs in the background of existing varicose veins, the disease progression as development of new varicose veins and appearance or exacerbation of venous symptoms can be expected. However, still, there is no evidence of the speed and frequency of preexisting CVD progression.

Pregnancy is also considered a high-risk factor for VTE in women. The incidence rate is 0.6 to 2.2 cases per 1000 deliveries and tends to have increased in recent decades. Compared with nonpregnant women of childbearing age, the relative risk of VTE increases 7 to 10 times during pregnancy and 15 to 35 times postpartum.37 Varicose veins are considered an independent minor risk factor in assessing antepartum and postpartum VTE risk by Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) guidelines.38 The combination of varicose veins with additional medical or obstetric factors may require pharmacological prophylaxis with low molecular weight heparin (LMWH).

Evidence of a 35-fold increase (95% CI, 19.1–63.8) in the risk of VTE associated with reproductive risk factors, including pregnancy, was observed in women with a history of SVT.39 However, there are still no reliable data on the frequency of perinatal SVT.

Dr Josnin. The risk of DVT and/or pulmonary embolism increases throughout pregnancy and peaks in the last trimester and postpartum period.40 The presence of varicose veins requires monitoring and compression stockings. In patients with risk factors for VTE or with a history of venous thrombosis, treatment with LMWH should be introduced. Most varicose veins occurring during pregnancy, including vulvar ones, disappear after pregnancy, which indicates that the patient should be re-evaluated at least 3 to 4 months after delivery.

Dr Geroulakos. Patients with varicose veins should be advised to use graduated compression stockings during pregnancy and may be considered for surgical intervention if they have symptoms affecting their QOL at least 6 months postpartum.

Dr Kan. During pregnancy, blood volume increases by 20% to 40% to ensure adequate nutrition for the fetus. In addition, as the pregnancy progresses, the growing uterus increases the pressure on the intra-abdominal and pelvic veins, leading to increased pressure in the leg veins. Treatment before pregnancy is advisable for overt and symptomatic varicose veins to avoid further development of varicose veins during pregnancy, and it ensures greater comfort during pregnancy. Some recurrences that develop can be efficiently dealt with by sclerotherapy after delivery. However, with asymptomatic varicose veins, follow-up and wearing compression stockings during pregnancy may be considered. After pregnancy, we can see the progression of the disease and then decide what to do next.

Dr Tazi Mezalek. Varicose veins affect about 40% of pregnant women. Although varicose veins may appear during pregnancy, pregnant women should be informed that they may regress during the postnatal period. Interventional treatment for varicose veins should not be considered for women during pregnancy unless in exceptional circumstances, such as with the presence of bleeding varicosities.

Dr Lobastov. No good evidence exists concerning this question. Pregnancy can provoke CVD and varicose vein deterioration with the development of complications. Particularly, untreated varicose veins are considered a risk factor for VTE that may require anticoagulation in combination with other factors.38 Pregnancy can also lead to a rapid recurrence of treated varicose veins. Pregnant women will be recommended to wear compression stockings irrespective of previous intervention.

Dr Dzhenina. When pregnancy occurs after surgical treatment of varicose veins, a recurrence with decreased QOL is possible, requiring the wearing of compression stockings and planning of a second intervention after delivery. With watchful waiting, the onset of pregnancy can provoke the progression of varicose veins, which could accompany an additional decrease in the QOL. It will also require the wearing of compression stockings and planning of intervention after delivery. So, there is no preferred solution. Considering varicose veins as a modifiable risk factor for perinatal VTE, preliminary removal can reduce thrombotic risk and, probably, decrease the need and burden of pharmacological prophylaxis.

Dr Josnin. The NICE recommendations insist on the fact that the consideration of a pregnancy or a new pregnancy should not delay the treatment of varicose veins if the indication has been established and that a delay of 3 to 6 months between a delivery and a treatment of varicose veins is acceptable.33

Dr Geroulakos. There is a general agreement that endothermal ablation is the treatment of choice for the management of saphenous trunks. The management of the tributaries is more controversial. Concomitant phlebectomy has the advantage of a holistic treatment of the varicose veins on the same admission. Phlebectomies at a second stage increase the cost of the procedure and the inconvenience to the patient, although some may have complete resolution of the varices with the saphenous trunk ablation and may be spared from a second procedure. Sclerotherapy of the tributaries could lead to hyperpigmentation of the skin, a complication most uncommon with phlebectomy, and a higher recurrence rate if their diameter is larger than 6 mm.

Dr Kan. I think the question depends on the country, health care payment issues, and recent developments in technology and equipment. To achieve the purpose of GSV removal, endovenous thermal ablation, nonthermal-nontumescent interventions, and even open surgical ligation with stripping can accomplish this purpose. Both phlebectomy and sclerotherapy can achieve good results for varicose tributaries, but large-scale phlebectomy may require general anesthesia to achieve painless surgical results. Even sclerotherapy can achieve good results, but for large sized tributaries, sometimes the thrombus formation after sclerotherapy may cause pain and a lumpy feeling, making the patient uncomfortable. I would recommend endovenous therapy, microphlebectomy, and sclerotherapy under local anesthesia as initial treatment.

Dr Lobastov. Considering the current evidence, the best method for GSV ablation is cyanoacrylate embolization (CAE), according to the technical success and postoperative pain level.17 However, CAE is the most expensive treatment method and associated with hypersensitivity reactions in 6% to 16%.41-44 In contrast, endovenous laser ablation therapy (EVLT) and radiofrequency ablation (RFA) are equally effective and relatively cheaper than CAE.41,45 Mechanochemical ablation (MOCA), in turn, is associated with a lower occlusion rate than with EVLT, but does not provide any advantages in perioperative or postoperative pain.46 Thus, thermal ablation of a GSV trunk with EVLT and RFA is preferable. Varicose tributaries could be removed with microphlebectomy or sclerotherapy simultaneously or in a delayed manner, according to the patient’s preferences. Compared with simultaneous treatment, delayed intervention is associated with lower improvement in disease severity and QOL within the first 12 months, although this difference disappears in long-term follow-up. According to a meta-analysis, the staged intervention is required in only 36% of patients after isolated ablation of the trunk.47

Dr Josnin. Although the ablation of the GSV trunk by a thermal method is nowadays unanimously recommended, the treatment of tributaries is much less so. The recommendations differ from one country to another. The literature does not allow us to answer the question, especially as no comparative study could be carried out, as the number of arms to be included would be too large: concomitant or deferred intervention, sclerotherapy or phlebectomy, if deferred, for how long, if the absence of treatment, for what end point, from from what diameter onwards should treatment be carried out, etc?

In this case, the choice was made to treat the thigh tributary because it was prominent and to leave the calf tributaries to evolve (deferred treatment if necessary).

Dr Geroulakos. The effect of endovenous procedures in managing varicose veins is independent of the patient’s age.

Dr Kan. I would still recommend endovenous therapy and microphlebectomy with sclerotherapy under local anesthesia as initial treatment for aged patients. But sometimes, in very elderly patients, I would recommend local sclerotherapy or symptomatic compression first.

Dr Nikolov. Regardless of age, thermal ablation techniques are always a first choice. We should consider the nonthermal techniques in selected patients with many comorbidities because they are less invasive and faster to perform than the others.

Dr Lobastov. Modern endovenous ablation methods under local tumescent anesthesia do not have any limitations by age. The efficacy and safety of EVLT and RFA are similar in patients over and younger than 75 years old.48,49 The patient’s mobility and ability to wear compression stockings when indicated are more important than formal age.

Dr Josnin. The patient’s age should not interfere with the choice of treatment because it is now accepted by all international recommendations that endovenous treatments under local tumescent anesthesia without sedation or phlebectomy under the same conditions are sufficient in most cases.

Dr Geroulakos. In a recent retrospective review, the authors reported that for patients who had undergone endothermal ablation for symptomatic saphenous venous reflux, the periprocedural use of direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) did not adversely affect the efficacy of endovenous ablation to ≥9 months. Furthermore, DOAC use did not confer additional risk of bleeding, DVT, or endovenous heat-induced thrombosis (EHIT) periprocedurally.50

Dr Nikolov. Clinical practice guidelines on the management of CVD of the lower limbs (European Society for Vascular Surgery [ESVS]) stated that it is safe to perform EVLT on anticoagulation therapy.32

Dr Tazi Mezalek. There is no link between chronic anticoagulation and bad outcomes for varicose vein surgery.

Dr Lobastov. The current evidence suggests no influence of chronic anticoagulation with vitamin K antagonist (VKA) or DOACs on the efficacy or safety of sclerotherapy, EVLT, and RFA.50-58 However, performing RFA over oral anticoagulation may increase the risk of technical failure in a short-term follow-up.55

Dr Josnin. It was decided to treat the patient as before, and she agreed. It is important to emphasize that anticoagulants do not change the management of these patients. Guidelines emphasize that anticoagulation is not a contraindication but also that the only anesthesia that should be used for thermal endovenous ablation is tumescent anesthesia, with very rare exceptions.59,60

Dr Geroulakos. Further research is required to establish whether micronized purified flavonoid fraction (MPFF) stops the progression of CVD.

Dr Kan. I recommend the use of MPFF with compression stockings to prevent the further development of CVD.

Dr Lobastov. There is no evidence that using MPFF can reduce or abolish CVD progression and varicose vein recurrence in humans. However, encouraging data were obtained from the studies with experimental venous hypertension in rats and hamsters. The first model suggested the creation of a femoral arteriovenous fistula in rats, leading to increased venous diameter, decreased valvular height, and the appearance of blood reflux on day 7 and later after surgery.61,62 Morphological changes were accompanied by leukocyte infiltration and inflammatory response in the venous wall. At the same time, administration of MPFF resulted in a decreased leukocyte infiltration and reduced reflux rate. The second experimental model suggested ligation of an external iliac vein in hamsters, leading to chronic venous hypertension accompanied by leukocyte rolling, adhesion, and dilating of distal veins starting 6 weeks after surgery.63 In small venules, the diameter increased immediately, reaching a maximum at 4 hours after surgery, accompanied by leukocyte adhesion, beginning simultaneously and achieving the peak at 3 days.64 Treatment with MPFF in such cases decreased leukocyte rolling and adhesion, as well as vein diameter, measured at 6 weeks for larger vessels and at 5 days for smaller ones. Thus, treatment with MPFF allowed for increasing venous resistance against high experimental hypertension. First human trials suggest that therapy with MPFF may abolish transitional reflux in the GSV.65 However, all these suggestions should be confirmed in robust RCTs.

Dr Josnin. In this patient, the practitioner can immediately prescribe compression and VADs. European guidelines indicate a Grade A level of recommendation: MPFF is strongly recommended for “treatment of pain, heaviness, feeling of swelling, functional discomfort, cramps, leg redness, skin changes, edema, and QOL.”29

Conclusion

• Pregnancy is a well-established and essential risk factor for developing CVD and varicose veins in women. However, the risk of further deterioration and complications of pre existing CVD in pregnancy is not established.

• The influence of hormonal contraception on the development and progression of CVD and varicose veins is controversial, and no clear guidelines for perioperative management exist. Based on the individual VTE risk, the decision to cease hormonal contraception and to use perioperative thromboprophylaxis should be made case by case.

• Scheduled pregnancy should not be considered as a contraindication for varicose vein surgery. However, there is no evidence of a better moment to perform an intervention before or after pregnancy, balancing the risk of complications and varicose vein recurrence.

• Modern endovenous interventions on varicose veins have no limitation by age and could be safely performed even in elderly patients receiving oral anticoagulants without their withholding.

• CVD is a steadily progressive disease that should be treated properly from the early stages. Experimental studies in animals encourage that treatment with MPFF can slow progression. However, these findings should be confirmed in well-controlled RCTs in humans.

CORRESPONDING AUTHOR

Matthieu Josnin

Clinique St Charles, 11 boulevard René

Levesque, 85000 La Roche sur Yon,

France

email: matthieu.josnin@gmail.com

References

1. Lee AJ, Robertson LA, Boghossian SM, et al. Progression of varicose veins and chronic venous insufficiency in the general population in the Edinburgh Vein Study. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2015;3(1):18-26.

2. Davies AH. The seriousness of chronic venous disease: a review of real-world evidence. Adv Ther. 2019;36(suppl 1):5-12.

3. Pannier F, Rabe E. Progression in venous pathology. Phlebology. 2015;30(suppl 1):95-97.

4. Michaels JA, Campbell WB, Brazier JE, et al. Randomised clinical trial, observational study and assessment of cost effectiveness of the treatment of varicose veins (REACTIV trial). Health Technol Assess. 2006;10(13):1-196, iii-iv.

5. Salim S, Machin M, Patterson BO, Onida S, Davies AH. Global epidemiology of chronic venous disease: a systematic review with pooled prevalence analysis. Ann Surg. 2021;274(6):971-976.

6. Ismail L, Normahani P, Standfield NJ, Jaffer U. A systematic review and meta analysis of the risk for development of varicose veins in women with a history of pregnancy. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2016;4(4):518-524 e1.

7. DeCarlo C, Boitano LT, Waller HD, et al. Pregnancy conditions and complications associated with the development of varicose veins. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2022;10(4):872-878.e68.

8. Kohno K, Niihara H, Hamano T, et al. Standing posture at work and overweight exacerbate varicose veins: Shimane CoHRE study. J Dermatol. 2014;41(11):964-968.

9. Brand FN, Dannenberg AL, Abbott RD, Kannel WB. The epidemiology of varicose veins: the Framingham study. Am J Prev Med. 1988;4(2):96-101.

10. Richardson JB, Dixon M. Varicose veins in tropical Africa. Lancet. 1977;1(8015):791-792.

11. Brewster S, Nicholson S, Farndon J. The varicose vein waiting list: results of a validation exercise. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1991;73(4):223.

12. Sarin S, Shields D, Farrah J, Scurr J, Coleridge-Smith P. Does venous function deteriorate in patients waiting for varicose vein surgery? J R Soc Med. 1993;86(1):21.

13. Labropoulos N, Leon L, Kwon S, et al. Study of the venous reflux progression. J Vasc Surg. 2005;41(2):291-295.

14. Kostas TI, Ioannou CV, Drygiannakis I, et al. Chronic venous disease progression and modification of predisposing factors. J Vasc Surg. 2010;51(4):900-907.

15. Rabe E, Pannier F, Ko A, Berboth G, Hoffmann B, Hertel S. Incidence of varicose veins, chronic venous insufficiency, and progression of the disease in the Bonn Vein Study II. J Vasc Surg. 2010;51(3):791.

16. Bootun R, Burrows M, Chowdhury MM, Stather PW, Al-Jundi W. The risk of harm whilst waiting for varicose veins procedure. Phlebology. 2023;38(1):22-27.

17. Siribumrungwong B, Wilasrusmee C, Orrapin S, et al. Interventions for great saphenous vein reflux: network meta analysis of randomized clinical trials. Br J Surg. 2021;108(3):244-255.

18. Richards T, Anwar M, Beshr M, Davies AH, Onida S. Systematic review of ambulatory selective variceal ablation under local anesthetic technique for the treatment of symptomatic varicose veins. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2021;9(2):525- 535.

19. Lobastov KV, Vorontsova AV, Laberko LA, Barinov VE. eASVAL Principle implementation: the effect of endovenous laser ablation of perforating vein and/ or sclerotherapy of varicose branches on the course of varicose disease in great saphenous vein system. Flebologiia. 2019;13(2):98-111.

20. Guo L, Huang R, Zhao D, et al. Long-term efficacy of different procedures for treatment of varicose veins: a network meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019;98(7):e14495.

21. Golovina VI, Seliverstov EI, Efremova OI, Panfilov VA, Zolotukhin IA. Great saphenous vein sparing segmental radiofrequency ablation in varicose veins patients. Flebologiya. 2022;16(3):220- 226.

22. Wong M, Parsi K, Myers K, et al. Sclerotherapy of lower limb veins: indications, contraindications and treatment strategies to prevent complications – a consensus document of the International Union of Phlebology-2023. Phlebology. 2023;38(4):205-258.

23. Greer I, Ginsberg J, Forbes C. Women’s vascular health. CRC Press; 2006.

24. Tepper NK, Marchbanks PA, Curtis KM. Superficial venous disease and combined hormonal contraceptives: a systematic review. Contraception. 2016;94(3):275- 279.

25. Health WHOR. Medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use: World Health Organization; 2015.

26. Suissa S, Blais L, Spitzer WO, Cusson J, Lewis M, Heinemann L. First-time use of newer oral contraceptives and the risk of venous thromboembolism. Contraception. 1997;56(3):141-146.

27. Dinger J, Möhner S, Heinemann K. Cardiovascular risks associated with the use of drospirenone-containing combined oral contraceptives. Contraception. 2016;93(5):378-385.

28. Wilson S, Chen X, Cronin M, et al. Thrombosis prophylaxis in surgical patients using the Caprini Risk Score. Curr Probl Surg. 2022;59(11):101221.

29. Nicolaides A, Kakkos S, Baekgaard N, et al. Management of chronic venous disorders of the lower limbs. Guidelines according to scientific evidence. Part I. Int Angiol. 2018;37(3):181-254.

30. Nicolaides A, Kakkos S, Baekgaard N, et al. Management of chronic venous disorders of the lower limbs. Guidelines according to scientific evidence. Part II. Int Angiol. 2020;39(3):175-240.

31. Nicolaides AN, Allegra C, Bergan J, et al. Management of chronic venous disorders of the lower limbs: guidelines according to scientific evidence. Int Angiol. 2008;27(1):1-59.

32. De Maeseneer MG, Kakkos SK, Aherne T, et al. Editor’s choice – European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS) 2022 clinical practice guidelines on the management of chronic venous disease of the lower limbs. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2022;63(2):184-267.

33. National Clinical Guideline Centre (UK). Varicose veins in the legs: the diagnosis and management of varicose veins. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE); 2013.

34. Bromen K, Pannier-Fischer F, Stang A, Rabe E, Bock E, Jöckel KH. Should sex specific differences in venous diseases be explained by pregnancies and hormone intake? [Article in German]. Gesundheitswesen. 2004;66(3):170-174.

35. Krasiński Z, Sajdak S, Staniszewski R, et al. Pregnancy as a risk factor in development of varicose veins in women. [Article in Polish]. Ginekol Pol. 2006;77(6):441-449.

36. Ropacka-Lesiak M, Kasperczak J, Breborowicz GH. Risk factors for the development of venous insufficiency of the lower limbs during pregnancy– part 1. [Article in Polish]. Ginekol Pol. 2012;83(12):939-942.

37. Tsikouras P, von Tempelhoff GF, Rath W. Epidemiology, risk factors and risk stratification of venous thromboembolism in pregnancy and the puerperium [Article in German]. Z Geburtshilfe Neonatol. 2017;221(4):161-174.

38. Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Reducing the risk of venous thromboembolism during pregnancy and the puerperium. Green-top Guideline No. 37a. Published April 2015. https://www.rcog.org.uk/media/qejfhcaj/ gtg-37a.pdf

39. Roach RE, Lijfering WM, van Hylckama Vlieg A, Helmerhorst FM, Rosendaal FR, Cannegieter SC. The risk of venous thrombosis in individuals with a history of superficial vein thrombosis and acquired venous thrombotic risk factors. Blood. 2013;122(26):4264-4269.

40. Jacobsen AF, Skjeldestad FE, Sandset PM. Incidence and risk patterns of venous thromboembolism in pregnancy and puerperium–a register-based case control study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198(2):233.e1-e7.

41. Epstein D, Bootun R, Diop M, Ortega Ortega M, Lane TRA, Davies AH. Cost effectiveness analysis of current varicose veins treatments. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2022;10(2):504-513.e7.

42. Gibson K, Minjarez R, Rinehardt E, Ferris B. Frequency and severity of hypersensitivity reactions in patients after VenaSeal™ cyanoacrylate treatment of superficial venous insufficiency. Phlebology. 2020;35(5):337-344.

43. Sermsathanasawadi N, Hanaroonsomboon P, Pruekprasert K, et al. Hypersensitivity reaction after cyanoacrylate closure of incompetent saphenous veins in patients with chronic venous disease: a retrospective study. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2021;9(4):910-915.

44. Murzina EL, Lobastov KV, Bargandzhiya AB, Laberko LA, Popov IB. Mid-term results of cyanoacrylate embolization of saphenous veins. Flebologiya. 2020;14(4):311-321.

45. Balint R, Farics A, Parti K, et al. Which endovenous ablation method does offer a better long-term technical success in the treatment of the incompetent great saphenous vein? Review. Vascular. 2016;24(6):649-657.

46. Lim AJM, Mohamed AH, Hitchman LH, et al. Clinical outcomes following mechanochemical ablation of superficial venous incompetence compared with endothermal ablation: meta-analysis. Br J Surg. 2023;110(5):562-567.

47. Aherne TM, Ryan ÉJ, Boland MR, et al. Concomitant vs. staged treatment of varicose tributaries as an adjunct to endovenous ablation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2020;60(3):430-442.

48. Tamura K, Maruyama T, Sakurai S. Effectiveness of endovenous radiofrequency ablation for elderly patients with varicose veins of lower extremities. Ann Vasc Dis. 2019;12(2):200-204.

49. Keo HH, Spinedi L, Staub D, et al. Safety and efficacy of outpatient endovenous laser ablation in patients 75 years and older: a propensity score matched analysis. Swiss Med Wkly. 2019;149:w20083.

50. Chang H, Sadek M, Barfield ME, et al. Direct oral anticoagulant agents might be safe for patients undergoing endovenous radiofrequency and laser ablation. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2023;11(1):25-30.

51. Stücker M, Reich S, Hermes N, Altmeyer P. Safety and efficiency of perilesional sclerotherapy in leg ulcer patients with postthrombotic syndrome and/or oral anticoagulation with phenprocoumon. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2006;4(9):734-738.

52. Reich-Schupke S, Doerler M, Altmeyer P, Stücker M. Foam sclerotherapy with enoxaparin prophylaxis in high-risk patients with postthrombotic syndrome. Vasa. 2013;42(1):50-55.

53. Theivacumar NS, Gough MJ. Influence of warfarin on the success of endovenous laser ablation (EVLA) of the great saphenous vein (GSV). Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2009;38(4):506-510.

54. Delaney CL, Russell DA, Iannos J, Spark JI. Is endovenous laser ablation possible while taking warfarin? Phlebology. 2012;27(5):231-234.

55. Sufian S, Arnez A, Labropoulos N, Lakhanpal S. Endothermal venous ablation of the saphenous vein on patients who are on anticoagulation therapy. Int Angiol. 2017;36(3):268-274.

56. Vatish J, Iqbal N, Rajalingam VR, Tiwari A. The outcome of anticoagulation on endovenous laser therapy for superficial venous incompetence. Vasc Endovascular Surg. 2018;52(4):245-248.

57. Westin GG, Cayne NS, Lee V, et al. Radiofrequency and laser vein ablation for patients receiving warfarin anticoagulation is safe, effective, and durable. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2020;8(4):610-616.

58. Sharifi M, Mehdipour M, Bay C, Emrani F, Sharifi J. Effect of anticoagulation on endothermal ablation of the great saphenous vein. J Vasc Surg. 2011;53(1):147-149.

59. Rabe E, Breu FX, Cavezzi A, et al. European guidelines for sclerotherapy in chronic venous disorders. Phlebology. 2014;29(6):338-354.

60. Gracia S, Miserey G, Risse J, et al. Update of the SFMV (French Society of Vascular Medicine) guidelines on the conditions and safety measures necessary for thermal ablation of the saphenous veins and proposals for unresolved issues. J Med Vasc. 2020;45(3):130-146.

61. Pascarella L, Schmid-Schönbein GW, Bergan J. An animal model of venous hypertension: the role of inflammation in venous valve failure. J Vasc Surg. 2005;41(2):303-311.

62. Pascarella L, Lulic D, Penn A, et al. Mechanisms in experimental venous valve failure and their modification by Daflon© 500 mg. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2008;35(1):102-110.

63. das Graças C de Souza M, Cyrino FZ, de Carvalho JJ, Blanc-Guillemaud V, Bouskela E. Protective effects of micronized purified flavonoid fraction (MPFF) on a novel experimental model of chronic venous hypertension. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2018;55(5):694-702.

64. Cyrino FZ, Blanc-Guillemaud V, Bouskela E. Time course of microvalve pathophysiology in high pressure low flow model of venous insufficiency and the role of micronized purified flavonoid fraction. Int Angiol. 2021;40(5):388-394.

65. Tsukanov YT, Tsukanov AY. Diagnosis and treatment of situational great saphenous vein reflux in daily medical practice. Phlebolymphology. 2017;24(3):144-151.