CLINICAL CASE 3. Challenging chronic venous disease treatment within the background of comorbidities

Chung-Dann Kan, MD, PhD

Department of Surgery, National

Cheng Kung University Hospital,

College of Medicine, National

Cheng Kung University, Tainan,

Taiwan

A 51-year-old female patient visited our cardiovascular surgery outpatient clinic with a chief complaint of small, visually obvious veins in her left leg, with soreness and pain sensation noted for years. She had no history of diabetes or hypertension. However, she had undergone splenectomy for an idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) state and a total abdominal hysterectomy 10 years earlier for a uterine mass and adenomyosis, complicated by pelvic adhesions the following year.

In the photo taken at her visit (Figure 1), we can see that the left leg is slightly thicker than the right, and there are apparent dermatitis and telangiectasia. Outpatient vascular ultrasound showed only mild dilation of the great saphenous vein without significant deep venous thrombosis. At first, I advised her to wear compression stockings and take micronized purified flavonoid fraction. She felt slightly improved in terms of soreness but still complained of leg swelling and dermatitis. So, she underwent computed tomography venography, which showed some compression of the left iliac vein. (Figures 2 and 3). I suggested that she undergo venous stent surgery; however, considering her hidden danger of ITP, she is still hesitant to have the operation. Up to this point, she has maintained her medication and lifestyle modification.

Figure 1. Clinical signs of chronic venous disease in patients. A photo taken during the medical visit shows the left calf with reticular veins, telangiectasias, and skin pigmentation in the lower third.

Figure 2. Results from computed tomography (CT) venography in the patient showing left-sided nonthrombotic iliac vein lesion. The lesion site is marked with a white arrow.

Discussion

Dr Kan. Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) is characterized by immune-mediated premature destruction of platelets, leading to thrombocytopenia and bleeding complications for patients. ITP usually manifests as hemorrhage. Paradoxically, sometimes it presents as thrombosis. Available data and evidence suggest an increased incidence of thromboembolism in patients with ITP, but the link between these two contradictory processes still needs to be studied in more detail.1

According to previous treatment experience of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and stenting combined with dual antiplatelet drugs (DAPT) in patients with ITP complicated by acute coronary syndrome (ACS), therapy to increase platelet counts for ITP and therapy to inhibit platelet activity for ACS are somewhat contradictory, and an imbalance between them can lead to life-threatening complications.2 Questions to be addressed for these patients include: (i) What should be the ideal minimum platelet count in treating such patients undergoing vein stenting with antithrombotic therapy? (ii) What is the ideal antiplatelet therapy for these patients? (iii) What is the mechanism of stent thrombosis in this patient? (iv) How do we avoid bleeding/thrombotic complications while maintaining adequate platelet counts and continuing antithrombotic therapy?

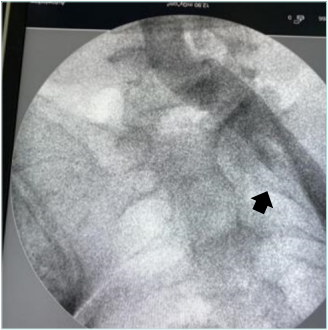

Figure 3. Venography in the patient showing a left-sided nonthrombotic iliac vein lesion. The lesion site is marked with a black arrow.

Dr Nikolov. There is no contraindication for venous stenting in patients with ITP, but I would prefer to use fondaparinux for postprocedural anticoagulation.

Dr Tazi Mezalek. There is a risk of bleeding in the case of ITP if the platelet count is below 50 x 109/L. If the platelet count is higher than this value, most of the procedures can be performed. The discussion will be about postprocedure anticoagulation. The symptoms of venous obstruction not being major, I propose a conservative treatment. ITP, even if in remission, may recur and interfere with chronic post procedure anticoagulation.

Dr Lobastov. There is no direct evidence for venous stenting in the setting of ITP, and different interventions may be limited by platelet level. So, minor surgery is recommended when the platelet count is >50 x 109/L, whereas major surgery and epidural anesthesia require a platelet count >80 x 109/L.3 After venous stenting is performed, antithrombotic therapy will be required, which may also be limited by platelet count. In the absence of direct recommendations for ITP, some suggestions from a population of patients with cancer associated thrombosis may be stated.4 When the platelet count is >50 x 109/L, full therapeutic doses of direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) or single antiplatelet treatment (SAPT) with low-dose aspirin or clopidogrel (in the absence of other major bleeding risk factors) may be administered. When the platelet count is 25-50 x 109/L, DOACs should be switched to low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) in half of the therapeutic or prophylactic dose, and SAPT should be withheld. When the platelet count is >50 x 109/L, full therapeutic doses of direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) or single antiplatelet treatment (SAPT) with low-dose aspirin or clopidogrel (in the absence of other major bleeding risk factors) may be administered. When the platelet count is 25-50 x 109/L, DOACs should be switched to low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) in half of the therapeutic or prophylactic dose, and SAPT should be withheld. When the platelet count is >25 x 109/L, antithrombotic treatment should be stopped until recovery of the platelet count. Considering the increased risk of intervention and complicated postoperative management, venous stenting may be avoided in patients with ITP.

Dr Kan. Combining antiplatelets and anticoagulants after venous stenting remains controversial. The international Delphi consensus on antithrombotic treatment after venous stenting looked at scenarios including nonthrombotic iliac vein lesion (NIVL; manifesting as May-Thurner syndrome caused by extravascular compression), residual obstruction after thrombolysis, and postthrombotic syndrome. It is recommended to treat these lesions. Recommendations reaching consensus for treatment of these lesions are as follows: i) anticoagulant therapy after stenting within 6 to 12 months (as the first choice); ii) LMWH for the first 2 to 6 weeks of treatment (this appears to be an option); iii) after multiple deep venous thrombosis (DVT) events, lifelong anticoagulation is recommended; iv) after venous stenting for 1 episode of DVT, it is suggested that anticoagulants be discontinued after 6 to 12 months. No consensus was achieved regarding the role of prolonged antiplatelet therapy.5

Considering idiopathic thrombocytopenia, there does not appear to be a best solution for antithrombotic therapy after venous stenting. However, in reports for those patients with ACS, some authors suggest that DAPT can be used when the platelet count is >30 x 109/L without bleeding.

Implanting a bare metal stent to shorten the course of clopidogrel treatment is an option. In some patients with chronic asymptomatic ITP (platelets >100 x 109/L), no bleeding complications have been reported with drug-eluted stent implantation and DAPT. Given the lack of high-quality scientific evidence on managing these patients to support recommendations about their treatment, treatment should be individualized to minimize both risks.6

Dr Nikolov. The most logical antithrombotic therapy would be fondaparinux—a short duration for NIVL (2-4 weeks) and no antithrombotics afterward.

Dr Tazi Mezalek. The management of patients with both thrombocytopenia and an indication for anticoagulation is challenging. Evidence to guide appropriate treatment in this setting is very limited. Some authors have suggested that the risk of thrombosis is even higher in patients with ITP who have a distinct indication for anticoagulation, particularly after administration of ITP treatments and improvement of thrombocytopenia. The optimal approach to the use of anticoagulation in an individual with thrombocytopenia, including decisions regarding the need for anticoagulation, dosage of anticoagulant, therapies to increase platelet count, and alternatives to anticoagulation if the risk of bleeding is deemed too high, is still in question.

Dr Lobastov. Stenting of NIVL seems to be safe and effective, with primary patency of 96% at 1 year, so the need for long term anticoagulation was critically appraised toward short term treatment with antiplatelets.7,8 Considering the increased bleeding risk in patients with ITP, treatment with clopidogrel for 3 to 6 months, driven by platelet count, may be justified.

Dr Josnin. The international chronic venous disease (CVD) guidelines assign a Grade A recommendation level to the use of micronized purified flavonoid fraction (MPFF) for skin changes, and the European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS) guidelines have recently taken this up.9,10

Dr Kan. MPFF may play a role in arresting the progression of CVD. I recommend that this patient use MPFF and compression stockings to prevent her further developing CVD. She still has some swelling, with a larger-sized left leg at the moment, and I advised her to have a venous stent placed. However, the patient declined this recommendation due to concerns about her ITP disease and future risk.

Dr Tazi Mezalek. The use of venoactive drugs (VADs) is considered an essential component of the medical treatment of CVD. Based on high-quality evidence, MPFF is highly effective in improving leg symptoms, edema, and quality of life (QOL) in patients with CVD. A systematic review and meta-analysis showed the effectiveness of MPFF across the spectrum of defined venous symptoms, signs, QOL, and treatment assessment by the physician.11 Regarding objective assessments of leg edema, and leg redness, the use of MPFF compared with placebo reduced ankle circumference and significantly improved skin changes.

Dr Lobastov. According to the meta-analysis performed within European guidelines for CVD, MPFF is the only VAD that can affect skin changes and is strongly recommended for this purpose9; the number needed to treat (NNT) to achieve improvement in skin changes is only 1.6, which is very high among all VADs according to different indications. The essential question is about treatment duration. The routinely recommended course of 2 to 3 months may not be enough for patients with progressive CVD, so they may benefit from a course of therapy that is prolonged up to 6 months.9

Conclusion

• Venous stenting for NIVL in patients with ITP may be challenging due to the increased risk of periprocedural bleeding, so the decision to stent should be made case by case considering platelet count and its dynamic changes.

• Platelet count should drive antithrombotic management after stenting of NIVL in ITP. Single antiplatelet therapy with clopidogrel for 3 to 6 months may be suggested.

• MPFF is the only VAD that can improve skin changes in patients with CVD and is strongly recommended for this indication. The duration of the treatment course is essential, and it may be prolonged up to 6 months to achieve benefits.

CORRESPONDING AUTHOR

Chung-Dann Kan

National Cheng Kung University

Hospital, 138, Sheng-Li Road, Tainan,

Taiwan, R.O.C. 704

email: kcd56@mail.ncku.edu.tw

References

1. Ali EA, Rasheed M, Al-Sadi A, Awadelkarim AM, Saad EA, Yassin MA. Immune thrombocytopenic purpura and paradoxical thrombosis: a systematic review of case reports. Cureus. 2022;14(10):e30279.

2. Shah AH, Anderson RA, Khan AR, Kinnaird TD. Management of immune thrombocytic purpura and acute coronary syndrome: a double-edged sword! Hellenic J Cardiol. 2016;57(4):273-276.

3. Matzdorff A, Meyer O, Ostermann H, et al. Immune thrombocytopenia – current diagnostics and therapy: recommendations of a joint working group of DGHO, ÖGHO, SGH, GPOH, and DGTI. Oncol Res Treat. 2018;4(suppl 5):1-30.

4. Falanga A, Leader A, Ambaglio C, et al. EHA Guidelines on management of antithrombotic treatments in thrombocytopenic patients with cancer. Hemasphere. 2022;6(8):e750.

5. Milinis K, Thapar A, Shalhoub J, Davies AH. Antithrombotic therapy following venous stenting: international Delphi consensus. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2018;55(4):537-544.

6. Bermejo N, Sigüenza R, Ibáñez F. Management of primary immune thrombocytopenia with eltrombopag in a patient with recent acute coronary syndrome. Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed). 2017;70(1):56-57.

7. Majeed GM, Lodhia K, Carter J, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of 12-month patency after intervention for iliofemoral obstruction using dedicated or non-dedicated venous stents. J Endovasc Ther. 2022;29(3):478-492.

8. Veyg D, Alam M, Yelkin H, Dovlatyan R, DiBenedetto L, Ting W. A systematic review of current trends in pharmacologic management after stent placement in nonthrombotic iliac vein lesions. Phlebology. 2022;37(3):157-164.

9. Nicolaides A, Kakkos S, Baekgaard N, et al. Management of chronic venous disorders of the lower limbs. Guidelines According to Scientific Evidence. Part I. Int Angiol. 2018;37(3):181-254.

10. 1De Maeseneer MG, Kakkos SK, Aherne T, et al. Editor’s choice – European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS) 2022 clinical practice guidelines on the management of chronic venous disease of the lower limbs. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2022;63(2):184-267.

11. Kakkos SK, Nicolaides AN. Efficacy of micronized purified flavonoid fraction (Daflon©) on improving individual symptoms, signs and quality of life in patients with chronic venous disease: a systematic review and meta analysis of randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trials. Int Angiol. 2018;37(2):143-154.