Compression therapy is not mandatory after lower limb varices endovenous treatment

Martin, 75003 Paris, France

Abstract

Compression therapy for varicose vein was widely admit by most vascular practitioners. Suddenly, in 2014, like a bolt from the blue, the Sox trial by Kahn et al1 affirmed that elastic compression stockings did not prevent postthrombotic syndrome after a first proximal deep vein thrombosis, hence their findings do not support routine wearing of elastic compression stockings after deep vein thrombosis. Several reviewers tried to find bias in this study without evident success. Therefore, if in severe chronic venous insufficiency, compression is questioned, the interest of compression therapy after thermal ablation or sclerotherapy then becomes more a subject of debate. Due to the weakness of the studies, the American and British guidelines cannot give us recommendations on compression after treatment of varicose veins, but only suggestions without real conviction. Regardless of the studies with or without compression after sclerotherapy or thermal ablation, regardless of the duration or the dose of compression, there is no evidence that compression is mandatory and it could even be deleterious sometimes.

Introduction

The use of compression therapy stockings has always been affirmed and taught as a dogma. In medical schools, all teachers affirm it as natural evidence. In mathematics and philosophy, an axiom is an indemonstrable truth that must be admitted and a postulate is a statement that is assumed true without proof. Some think that many years or decades of experience are enough to reinforce their impression of having the truth. However, in medicine, a personal impression does not allow for giving guidelines. Only studies can guide therapeutic choices and the best ones are randomized controlled trials (RCT). On the one hand, compression stockings or medication cannot prevent the evolution of varicose veins. Palfreyman and Michaels2 analyzed data from 11 prospective RCTs or systematic reviews, 12 nonrandomized studies, and 2 guidelines, concluding that, although compression improved symptoms, evidence is lacking to support compression garments to decrease progression or to prevent recurrence of varicose veins after treatment. On the other hand, compression stockings or venoactive drugs will find their use in the presence of venous symptomatology. Do we have to prescribe elastic bandages or compression stockings after thermal, chemical and combined ablation, and with which strength, class 2, class 3, or more? For how long, 2 days, 1 to 4 weeks, or more? There is no consensus as well evidence to reply to these questions.

Role of compression: hypotheses

What is the role of compression? Is it to improve treatment efficacy, reduce postoperative pain and bruising, reduce the risk of deep vein thrombosis and improve quality of life scores during convalescence?

Compression serves at least five purposes according to the hypotheses of Goldman et al3: (i) provide direct apposition of the treated vein walls to produce a more effective fibrosis; (ii) decrease the extent of thrombus formation that inevitably occurs with the use of all sclerosing solutions, thus decreasing the risk for recanalization of the treated vessel; (iii) decrease the extent of thrombus formation may also decrease the incidence of postsclerotherapy pigmentation; (iv) limiting thrombosis and phlebitic reactions may prevent the appearance of angiogenesis/telangiectatic matting; and (v) improve the function of the calf muscle pump because compression stockings will narrow the vein diameter, restoring competency to its valvular function, which decreases retrograde blood flow. External pressure will also retard the reflux of blood from incompetent perforating veins into the superficial veins. These assumptions are very theoretical and must be proven by RCT studies.

Compression after sclerotherapy

Compression after sclerotherapy for the great saphenous vein and the small saphenous vein

In an RCT by Hamel-Desnos et al in 2010,4 which was performed at two centers, the outcome of foam sclerotherapy for the great saphenous vein and small saphenous vein with compression (15 to 20 mm Hg worn during the day for 3 weeks) or without compression was compared. The occlusion rate was 100% in both groups (assessments were done by independent experts). Side effects were few with no statistical difference between the two groups: no difference concerning deep vein thrombosis occurence, phlebitis, pigmentation, matting, pain, and quality of life (QOL). Patient satisfaction scores were high in both groups.

Partsch5 commented about this study, saying that the compliance rate was mediocre, only 40% of patients wore compression stockings every day, but the results without compression are so good that it would have been very difficult to obtain a superior outcome even by using stronger and more consistent compression. However, if just 40% of the patients wore compression stockings every day this does not mean that 60% of the patients did not wear compression at all, but rather less than 7 days a week, which corresponds to the data found in other studies.

Compression after sclerotherapy for telangiectasias and reticular leg veins

In another RCT (single-center) by Kern et al,6 patients were randomized to wear medical compression stockings (23 to 32 mm Hg) daily for 3 weeks or no compression after treatment of telangiectasias and reticular veins on the lateral aspect of the thigh in a single session of standardized liquid sclerotherapy (chromated glycerin). Outcomes were assessed by a patient satisfaction analysis and a quantitative evaluation of photographs taken from the lateral aspect of the thigh before and again at 52 days (on average) after sclerotherapy by two blinded expert reviewers. The rate of pigmentation and matting was low and did not differ significantly between the two groups. Independent experts found better results according to the photos by improving clinical vessel disappearance for the compression group, but patient satisfaction was similar in both groups. What is best, the opinion of experts or patients?

According to Partsch,5 based on experience, he said, I would still recommend applying good compression especially after injection into the superficial side-branches in order to prevent phlebitis and hyperpigmentation. However, as we will see later, no compression stockings can narrow and, even less, completely compress the superficial vein, especially in the thigh while standing.

Compression after thermal ablation

To date, 5 RCTs and a meta-analysis have been published. In 2013, Bakker et al7 compared compression stockings after endovenous laser ablation (EVLA) of the great saphenous vein for 48 hours vs 7 days (n=69 patients). After 1 week, the pain score as evaluated with the visual analog scale (VAS) was 3.7±2.1 vs 2.0±1.1. He concluded that compression stockings for longer than 2 days reduced pain and improved physical function during the first week after treatment.

In 2014, Elderman et al8 randomized 111 patients to either 24 hours of bandages or 24 hours of bandages plus 2 weeks of elastic compression stockings following EVLA. He concluded that there was small significant reduction in postoperative pain and the use of analgesics compared with not wearing compression stockings. In an RCT published in 2016, Krasznai et al9 compared 4 hours of leg compression with 72 hours of leg compression following radiofrequency ablation (RFA). They found no difference in leg edema pain, postoperative pain, and time to full recovery. He concluded that a shorter duration of compression had fewer complications (eg, blistering, skin irritation).

In 2016, Ye K et al10 randomized 400 patient to either elastic compression stockings or no compression after EVLA. In the first week, patients in the elastic compression stocking group experienced less pain according to the VAS score (2.3±1.4 vs 3.3±1.6) and edema. He concluded that elastic compression stockings provided no benefit in QOL and mean time to return to work, but reduced the severity of pain and edema during the first week. In 2017, Ayo D et al11 randomized 70 patients after RFA (91%) and EVLA (9%) to either thigh-high compression stocking (30 to 40 mm Hg) for 7 days or no compression. No significant differences in pain scores at day 7 (mean, 2.11 vs 2.81), CIVIQ-2 scores at 1 week (mean, 36.9 vs 35.1), and bruising score (mean, 1.2 vs 1.4) were observed. He concluded that compression might be an unnecessary adjunct following great saphenous vein ablation.

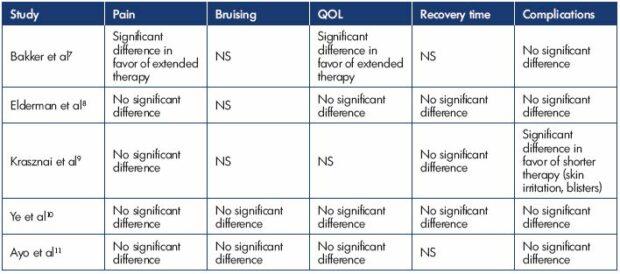

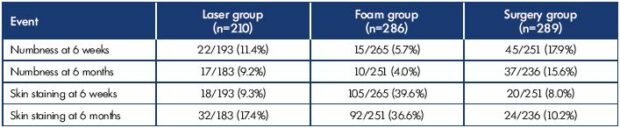

In 2018, Al Shakarchi J et al12 published a systematic review and meta-analysis statement on the role of compression after endovenous ablation of varicose veins. The primary outcomes for this study were the pain score and complications. The secondary outcomes were time to full recovery, quality of life score, leg circumference, bruising score, and compliance rates. Five studies (the five studies discussed above) were analyzed, which included 734 patients in total. Short-duration compression therapy ranged from 4 hours to 2 days and the longer duration ranged from 3 to 15 days. He found that a single study showed a better outcome in terms of complications with short-duration compression therapy; a single study showed a better outcome in terms of complications with a short duration of compression therapy; a single study showed benefit on pain and QOL with extended compression therapy, whereas the others did not. There was no significant difference in terms of bruising, recovery time, and leg swelling (Table I). He concluded that there is no evidence for the extended use of compression after endovenous ablation of varicose veins.

In my daily practice, I routinely prescribe class 2 compression stockings after thermal ablation. I put the compression stockings on myself and they are to be kept on day and night for 4 days and then only during the day, but I provide a very precise recommendation to remove the stockings if they are painful or uncomfortable and to take a shower.

Table I. The effect of compression therapy after endovenous ablation of varicose veins.

Abbreviations: NS, not specified; QOL, quality of life

Modified from reference 12. Al Shakarchi J et al. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2018;6(4):546-550.

© 2018, Society for Vascular Surgery.

Duration of compression

Regularly, the optimal duration of compression has come into question. Should they be worn for 2 days, 1 to 4 weeks, or more? In 2007, Biswas et al13 published a prospective study that randomized patients to either 1 week or 3 weeks of compression after high ligation and stripping of the saphenous vein. They found no benefit of wearing compression stockings for more than 1 week with respect to postoperative pain, number of complications, time to return to work, or patient satisfaction for up to 12 weeks following surgery.

The UK recommendations (NICE),14 based on two studies,4,15 suggest not offering compression bandaging or hosiery for more than 7 days after completion of interventional treatment of varicose veins.

In 2009, Houtermans-Auckel et al15 reported their study in which patients were randomized to 4 weeks of compression stockings or no compression after ligation and stripping of the great saphenous vein. There were no between-group differences in leg edema, pain, or other complications (bleeding, infection, seroma, and paresthesia). However, there was a statistically significant difference in the number of days of sick leave in favor of the no compression group (11 days vs 15 days). The reason could be that patients would still feel sick with compression stockings, which is why the UK guidelines14 recommend that patients can be advised that, in most cases, they are able to return to work while wearing compression bandaging or hosiery.

In 2016, El-Sheikha et al16 sent a postal questionnaire to 348 consultant members of the Vascular Society of Great Britain and Ireland. Among those who responded (41% surgeons, representing at least 61% of the vascular units), all surgeons prescribed compression. Following ultrasound-guided foam sclerotherapy, the median time was 7 days (range 2 days to 3 months) and, after endothermal ablation, 10 days (range 2 days to 6 weeks). Different combinations of bandages, pads, and compression stockings were reported. They concluded that compression regimes after treatments for varicose veins vary significantly and more evidence is needed to guide practice.

The 2019 US guidelines17 say that, in the absence of convincing evidence, we should recommend using our best clinical judgment to determine the duration of compression therapy after sclerotherapy or thermal ablation with no gradation.

Dose of compression

In 2005, Partsch and Partsch18 investigated the external pressure necessary to narrow and occlude leg veins in different body positions. Initial narrowing occurs with a median pressure between 30 and 40 mm Hg in the sitting and standing positions on the leg. Complete occlusion of superficial and deep leg veins occurs with 20 to 25 mm Hg in the supine position, between 50 and 60 mm Hg in the sitting position, and at about 70 mm Hg in the standing position.

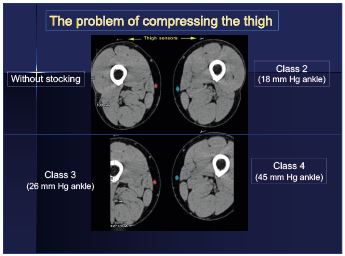

In the supine position, Uhl and Lun19 compared the great saphenous vein using a CT scan in patients wearing no compression, class II stockings (18 mm Hg ankle), class III stockings (26 mm Hg ankle) or class IV stockings (45 mm Hg ankle). Regardless of compression, there was no effect on the great saphenous vein. Compression cannot narrow the great saphenous vein on the thigh (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Stockings at the thigh are useless: regardless of the

compression, there is no effect on the great saphenous vein on

the thigh.

Modified from reference 19. Uhl JF, Lun B. Proc Int. Sympo

CNVD. 2004;3:135-138.

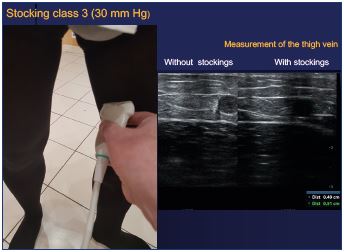

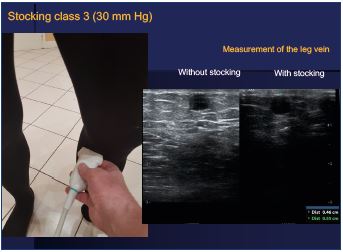

It is quite easy to check this information by echography. Personally, I have measured the great saphenous vein on the middle part of the thigh and on the upper part of the leg, the patients in a standing position wearing class III stockings (30 mm Hg) or nothing. As shown in the images (Figures 2 and 3), measurements are equivalent with elastic stockings (through the stocking) or without (directly on the skin).

Shouler et al20 concluded that 15 mm Hg of compression was as effective as 40 mm Hg in terms of minimizing bruising and thrombophlebitis after saphenous stripping, but low compression stockings proved to be more comfortable. After sclerotherapy, bandaging is not required if a high-compression stocking is used. Conversely, Cavezzi et al21 concluded that compression with 23 and 35 mm Hg medical compression stockings after catheter foam sclerotherapy plus phlebectomy was effective and well tolerated during the immediate- and short-term. Nevertheless, compression with 35 mm Hg medical compression stockings provided fewer adverse postoperative symptoms and a slightly better improvement in edema.

Figure 2. Compression stocking (30 mm Hg): measurements

by echography on the thigh are equivalent without and with

stockings.

Figure 3. Compression stocking (30 mm Hg): measurements

by echography on the leg are equivalent without and with

stockings.

In France, the maximum pressure of a compression stocking is about 45 mm Hg, unless the patient wears a double stocking, which is unbearable and quite impossible to put on. Thus, the theory that direct apposition of the treated vein walls produce a more effective fibrosis and decrease the extent of thrombus formation is completely erroneous.

Compliance

Compliance with compression therapy in chronic venous disease is still a subject of debate as most patients are not using compression therapy as pre

scribed; therefore, how can compliance be improved. In 2007, Raju published22,23 a study to assess the compliance of 3144 new chronic venous disease patients seen from 1998 to 2006. Only 21% of patients reported using the stockings on a daily basis, 12% used them on most days, and 4% used them less often. The remaining 63% did not use the stockings at all or abandoned them after a trial period.

In 2017, Soya et al24 assessed compliance in a Sub-Saharan population (Ivory Coast). The majority of patients (75%) agreed to wear their stockings after prescription with a good compliance rate of 58.5% at the beginning of the prescription. During the study, they found that 11% wore the compression stockings with an optimal duration of compliance of 6 months. Over 12 months, this rate fell to 7.5%. In 2018, Ayala et al25 also assessed the compliance in a tropical country (Colombia), where 31.8% of the patients reported wearing compression stockings as prescribed, 31.4% reported wearing compression stockings on most days, 28.3% reported wearing compression stockings intermittently, and 8.5% reported not wearing compression stockings at all.

Uhl et al26 published a study where the real compliance to compression therapy was objectively measured with a thermal probe inserted in the stocking that recorded the skin temperature every 20 minutes for 4 weeks. Therefore, the wearing of stockings was accurately recorded, which permitted the actual number of hours per day and days per week during which the compression was worn to be estimated. The average daily wearing time was only 5.6 hours and the average number of days worn per week was only 3.4 days. When patients have extensive and weekly recommendations, just during 4 weeks, the average daily wearing time was increased to 8 hours and the average number of days worn per week was 4.8 days. Even with repeated and clear recommendations, compliance improved, but, on average, compression was not worn the entire day and not every day, which is the real objective. In all other studies, the compliance rate was subjective and relied on the allegations of patients who sometimes do not want to disappoint the practitioner and gives information that does not exactly correspond to reality.

Compliance with wearing elastic compression stockings is mediocre. Most patients are not using compression therapy as prescribed. Heat in hot countries or during the hot season aggravates this poor compliance. Furthermore, over the long term, compliance gets worse. The main factors for noncompliance are discomfort, threading difficulties, skin problems (itching), unattractive, unfavorable working environment, and patient neglect. Another factor for the poor compliance is the cost of the stockings, which must be regularly renewed, ideally at least every 6 months.

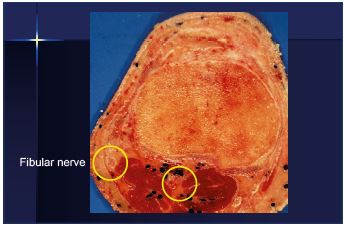

Paresthesia

In the study by Brittenden et al,27 they found that, after foam sclerotherapy, the rate of numbness at 6 weeks on average was 5.7% and at 6 months 4.0% (Table II). After traditional surgery, the paresthesia rate was usual around 15%. After laser ablation, paresthesia may occur, but at a much lower rate. Conversely, the main benefit of sclerotherapy is the absence of paresthesia. As you do not heat the vein wall, it is quite impossible to damage the nerve. Surprisingly, in this article, there are no comments about why numbness happens after sclerotherapy. When it occurs, it is probably due to excessive compression by bandages. The use of compression stockings after sclerotherapy, which is often recommended, has not yet been proven useful, but can sometimes be potentially deleterious. Probably much more with bandages than with stockings, especially on the lateral aspect at the upper part of the leg, where the fibular nerve is very superficial (Figure 4) and it could be damaged by excessive compression.

Guidelines

The 2011 US guidelines28 suggest using compression therapy for patients with symptomatic varicose veins (grade 2C), but recommend against compression therapy as the primary treatment if the patient is a candidate for saphenous vein ablation (grade 1B)

The 2019 US guidelines17 recommend the following:

After surgical or thermal procedures for varicose veins: (i) guideline 1.1: when possible, use compression (elastic stockings or wraps) (grade 2 C); (ii) guideline 1.2: if compression dressings are to be used post-procedurally, those providing pressures >20 mm Hg together with eccentric pads placed directly over the vein ablated or operated on provide the greatest reduction in postoperative pain (grade 2B); (iii) guideline 2.1: in the absence of convincing evidence, we recommend best clinical judgment to determine the duration of compression therapy after thermal ablation or stripping of the saphenous veins treatment

Table II. Numbness after foam sclerotherapy: 5.7% at 6 weeks and 4.0% at 6 months.

Modified from reference 27. Brittenden J et al. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(13):1218-1227. © 2014, Massachusetts Medical Society.

After sclerotherapy for varicose veins: (i) guideline 3.1: use compression therapy immediately after treatment of superficial veins to improve the outcomes of sclerotherapy (grade 2C); (ii) guideline 3.2: in the absence of convincing evidence, it is recommended to use the best clinical judgment to determine the duration of compression therapy after sclerotherapy.

The 2013 UK recommendations (NICE)14 say that, as there is no convincing evidence for using or not using compression therapy, the Guideline Development Group felt that they could not make a recommendation.

Figure 4. The fibular nerve is very superficial at the upper part

and lateral aspect of the leg, which means that compression

could be deleterious. Image courtesy of Professor Gillot.

Due to the small number, the weakness of the studies, and the lack of real evidence, the American and British recommendations cannot give us recommendations on compression after treatment of the varicose veins, but only suggestions without real conviction. So must we prove that compression is not mandatory or prove that compression is necessary?

Conclusion

Compression therapy in the treatment of leg ulcers is the main factor of success and cannot be called into question. All the guidelines recommend compression therapy to aid healing of venous ulceration. For patients with deep venous reflux, compression therapy is needed in the long term. For patients with chronic venous insufficiency, compression may not be necessary, but, depending on the symptomatology and in any case, it must be prescribed in a reasonable way and never as an obligation that cannot be discussed. To have the best compliance, especially for the long term, you have to advise the patients of the benefits of this treatment and repeat the recommendations regularly. Only on this condition can you expect the patient to adhere to the treatment. After thermal or chemical ablation, as there is no convincing evidence for using or not using compression therapy, you should let people feel free to assess whether they are benefiting from it or not.

To improve compliance, the hosiery must be prescribed carefully (not too strong or too light) and be measured properly in an orthopedic shop will ensure that you get a garment (knee highs, stockings, or pantyhose) that fits properly, which will be worn and not left in a drawer. Regarding stocking manufacturers, compression is not mandatory, but it does not mean no compression at all, but a prescription is often necessary, depending on the symptomatology and in agreement with the patient.

To the question, doctor should I wear compression stockings? You can answer, no it is not mandatory. After this question, you can ask your patients if they feel better when wearing the stockings? If the answer is yes, then put them on, and, if it is no, take them off! Compression must be a comfort and not a constraint. Why compel your patient to use compression therapy that he will stop because he cannot feel any advantage or that the stress is more important than the benefit? Why let your patients feeling guilty about the bad results of your treatment because they have not worn their compression therapy?

It is better to explain to your patients the benefits of compression and leave them free to wear according to the well-being felt.

REFERENCES

1. Kahn SR, Shapiro S, Wells PS, et al; SOX Trial Investigators. Compression stockings to prevent post-thrombotic syndrome: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2014;383(9920):880-888.

2. Palfreyman SJ, Michaels JA. A systematic review of compression hosiery for uncomplicated varicose veins. Phlebology. 2009;24(suppl 1):13-33.

3. Goldman MP, Bergan JJ, Guex JJ, eds. Sclerotherapy: Treatment of Varicose and Telangectatic Leg Veins. 4th edition. New York, NY: Mosby Elsevier; 2006:148-149.

4. Hamel-Desnos CM, Guias BJ, Desnos PR, Mesgard A. Foam sclerotherapy of the saphenous veins: randomised controlled trial with or without compression. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2010;39(4):500-507.

5. Partsch H. www.venousdigest.com 2010;17(3).

6. Kern P, Ramelet AA, Wütschert R, Hayoz D. Compression after sclerotherapy for telangiectasias and reticular leg veins: a randomized controlled study. J Vasc Surg. 2007;45(6):1212-1216.

7. Bakker NA, Schieven LW, Bruins RM, van den Berg M, Hissink RJ. Compression stockings after endovenous laser ablation of the great saphenous vein: a prospective randomized controlled trial. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2013;46(5):588-592

8. Elderman JH, Krasznai AG, Voogd AC, Hulsewé KW, Sikkink CJ. Role of compression stockings after endovenous laser therapy for primary varicosis. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2014;2(3):289-296.

9. Krasznai AG, Sigterman TA, Troquay S, et al. A randomised controlled trial comparing compression therapy after radiofrequency ablation for primary great saphenous vein incompetence. Phlebology. 2016;31(2):118-124.

10. Ye K, Wang R, Qin J, et al. Postoperative benefit of compression therapy after endovenous laser ablation for uncomplicated varicose veins: a randomised clinical trial. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2016;52(6):847-853.

11. Ayo D, Blumberg SN, Rockman CR, et al. Compression versus no compression after endovenous ablation of the great saphenous vein: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Vasc Surg. 2017;38:72-77.

12. Al Shakarchi J, Wall M, Newman J, et al. The role of compression after endovenous ablation of varicose veins. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2018;6(4):546- 550.

13. Biswas S, Clark A, Shields DA. Randomised clinical trial of the duration of compression therapy after varicose vein surgery. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2007;33:631-637.

14. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Varicose veins: diagnosis and management. http://guidance.nice.org.uk/ cg168. Published July 24, 2013. Accessed July 19, 2017.

15. Houtermans-Auckel JP, van Rossum E, Teijink JA, et al. To wear or not to wear compression stockings after varicose vein stripping: a randomised controlled trial. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2009;38(3):387- 391.

16. El-Sheikha J, Nandhra S, Carradice D, et al. Compression regimes after endovenous ablation for superficial venous insufficiency. Phlebology. 2016;31(1):16-22.

17. Lurie F, Lal BK, Antignani PL, et al. Compression therapy after invasive treatment of superficial veins of the lower extremities. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2019;7(1):17-28.

18. Partsch B, Partsch H. Calf compression pressure required to achieve venous closure from supine to standing positions. J Vasc Surg. 2005;42:734-738.

19. Uhl JF, Lun B. Proceedings of the IIth International Symposium on computeraided noninvasive vascular diagnostics. 2004;3:135-138.

20. Shouler PJ, Runchman PC. Varicose veins: optimum compression after surgery and sclerotherapy. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1989;71:402-404.

21. Cavezzi A, Mosti G, Colucci R, Quinzi V, Bastiani L, Urso SU. Compression with 23 mmHg or 35 mmHg stockings after saphenous catheter foam sclerotherapy and phlebectomy of varicose veins: a randomized controlled study. Phlebology. 2019;34(2):98-106.

22. Raju S1, Hollis K, Neglen P Use of compression stockings in chronic venous disease: patient compliance and efficacy. Ann Vasc Surg. 2007;21(6):790-795.

23. Raju S. Compliance with compression stockings in chronic venous disease. Phlebolymphology. 2008;15(3):103-106.

24. Soya E, N’djessan JJ, Koffi J, Monney E, Tano E, Konin C. Factors of compliance with the wearing of elastic compression stockings in a Sub-Saharan population [article in French]. J Med Vasc. 2017;42(4):221-228.

25. Ayala Á, Guerra JD, Ulloa JH, Kabnick L. Compliance with compression therapy in primary chronic venous disease: Results from a tropical country. Phlebology. 2018 Sep 6. Epub ahead of print.

26. Uhl JF, Benigni JP, Chahim M, Fréderic D. Prospective randomized controlled study of patient compliance in using a compression stocking: importance of recommendations of the practitioner as a factor for better compliance. Phlebology. 2018;33(1):36- 43.

27. Brittenden J, Cotton SC, Elders A, et al. A randomized trial comparing treatments for varicose veins. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(13):1218-1227.

28. Gloviczki P, Comerota AJ, Dalsing MC, et al. The care of patients with varicose veins and associated chronic venous diseases. J Vasc Surg. 2011;53(suppl 5):2S-48S.