Diagnosis and treatment of situational great saphenous vein reflux in daily medical practice

A. Yu. TSUKANOV,

Omsk State Medical University, Omsk,

Russia

Abstract

Aim: To analyze the treatments for situational great saphenous vein (GSV) reflux.

Methods: Patients with chronic venous disease who were classified as C0s, C0,1s, and C2 (n=294) were analyzed using a day orthostatic load (DOL) test. Situational GSV reflux occurred in 78 patients. The patients classified as C0s and C0,1s (group 1; n=46) and the patients with reflux still present after surgery on varicose tributaries (group 3; n=10) received micronized purified flavonoid fraction (MPFF) 1000 mg daily for 90 days. Patients classified as C2 with situational reflux (group 2; n=32) underwent elimination of their varicose tributaries.

Results: MPFF eliminated the evening GSV reflux in 35 patients (76.1%) and decreased the GSV evening diameters from 5.49 mm to 5.09 mm for patients in group 1. Surgery eliminated the GSV reflux in 22 lower limbs (68.8%) and reduced the evening GSV diameter from 6.27 mm to 4.41 mm for patients in group 2. The combination of surgery and MPFF treatment eliminated the GSV reflux in 4 patients in group 3. The global index score (CIVIQ-20) decreased from 50.63±7.43 to 29.33±7.18.

Conclusion: A situational GSV reflux was detected in 33.3% of the patients classified as C0s, C1s, and C2. A GSV reflux needs to be analyzed in detail using a DOL test. Out of the 78 patients with a situational reflux, 78.2% recovered the full function of the GSV due to MPFF treatment for C0s and C1s patients or a combination of MPFF therapy and surgery to eliminate the varicose tributaries for C2 patients.

Introduction

Starting from Trendelenburg, great saphenous vein (GSV) reflux is considered the main hemodynamic phenomenon and surgical target of varicose veins.1,2 GSV reflux surgery is supposed to be the leading technique to treat varicose veins.

However, the problem of varicose veins after surgery has not been solved. In 3 to 5 years after stripping or ablating the GSV, the frequency of postoperative progression ranges from 15%–20% to 46.5%–54.7%.3,4 Of note, the long-term results do not depend on the stripping or ablation techniques.4 During GSV stripping or ablation, the main, non-doubled trunk that drains the blood from the subcutaneous tissue of the limb is eliminated, making this the main factor leading to postoperative varicose vein progression, not the technique itself.

While there is no alternative to GSV removal when the trunk is irreversibly changed, it is not clear whether the GSV needs to be eliminated in all cases of primary varicose veins. Pittaluga and Chastanet5 showed that it might be possible to recover GSV function after eliminating its varicose tributaries. Other groups have shown the same results.6-8 Research using the day orthostatic load (DOL) test as a preoperative criterion for GSV preservation is of great interest.9 Modern data about the peculiarities of GSV reflux and the possible connection between mild and varicose forms of chronic venous disease were obtained by using the DOL test in patients with phlebopathy.10 The GSV reflux that appeared in some patients after a prolonged working day and disappeared after sleeping/resting was called transient reflux. In addition, treatment with micronized purified flavonoid fraction (MPFF) eliminated the transient GSV reflux.10 This data shows that the GSV reflux is predetermined by external (prolonged orthostasis) and internal (hypervolemia in varicose tributaries) factors that can be controlled.

Thus, some important questions arise:

– If one can save a weakened, but functioning, GSV, are there any tools to support its function?

– How effectively can drug therapy deal with this problem?

The answers received should not only correspond to the theory, but also find their place in daily practical implementation.

Aim

This single-center study aimed to analyze the treatment of situational GSV reflux in patients with primary varicose veins based on the functional assessment of the GSV during standard medical practice in one medical center.

Methods

All patients underwent repeated clinical and duplex ultrasonography. The key feature was the functional orientation, which was realized by assessing the GSV response to the day orthostatic load using the DOL test.9 A previously proposed 4-grade division was used to characterize the evening leg heaviness, a basic chronic venous disease symptom. This 4-grade division takes into account the functionality of the venous system based on the patient’s orthostatic load11: grade 0, no heaviness in the legs; grade 1, heaviness in the legs that occurs occasionally at the end of the day and with an increased load; grade 2, heaviness in the legs that occurs continuously with an increased load; and grade 3, heaviness in the legs that occurs continuously with a usual load.

All patients underwent a duplex ultrasonography examination using the SonoScape S6 system (SonoScape Co Ltd, Shenzhen, China). A special feature of the study was to conduct the ultrasonography in an upright position twice a day: in the evening at post loading status (after 6 pm) and in the morning after sleeping (before 10 am). Alterations in the extent and duration of the GSV reflux and diameter were assessed. A reflux duration was considered pathologic if it was >0.5 seconds.12 The extent of the GSV reflux was evaluated according to the general number of zones of reflux, which included three thigh and three calf zones.9 The reflux localization was described using the differentiation published by Engelhorn et al.13

The GSV response to the day orthostatic load was evaluated using duplex ultrasonography and included determining both the evening diameter of the GSV at the saphenofemoral junction (mm) and the orthostatic gradient (mm), which is the difference between the evening and morning values for the GSV. As opposed to a constant GSV reflux, a situational reflux has significant differences between the morning and evening values and the values of the GSV itself.

Patients classified C0s, C0,1s, and C2 according to the clinical, etiological, anatomical, and pathophysiological (CEAP) classification were examined. The C0s, C0,1s patients underwent an examination 3 months after treatment with MPFF, and the C2 patients were examined 1 month after a phlebectomy; patients who still had GSV reflux after surgery were also examined 3 months after MPFF treatment. At baseline and at the end of the treatment, the intensity of the symptoms, such as heavy legs, was measured on a10-cm visual analog scale. The quality of life was assessed using a self-questionnaire CIVIQ-20, its global index score ranges from 0 to 100.

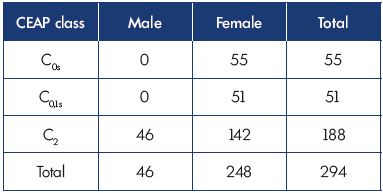

A total of 294 patients (male, n=46; female, n=248) with C0s, C0,1s, C2 were examined from 2014 to 2016. The average age was 41.5 years (range, 20 to 63). Classification of the patients according to CEAP was done based on the results of ultrasonography that was performed after sleeping. The inclusion criteria included patients with C0s, C0,1s, C2 and an informed consent to participate in the study. Table I shows the age and sex differentiation of the patients.

Table I. Age and sex differentiation of the patients who visited

the clinic over a 3-year period (2014–2016) according to the

CEAP classification.

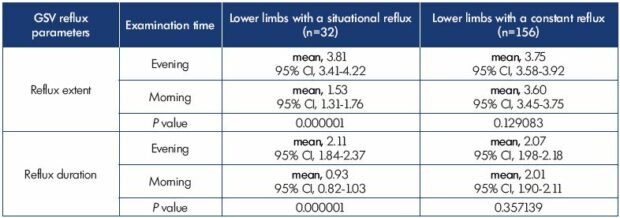

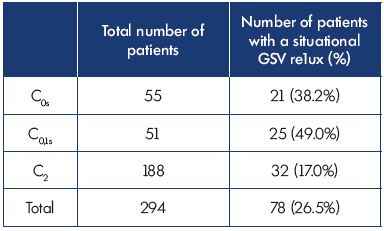

Out of the total number of patients (n=294), 234 had an evening GSV reflux. The DOL test showed that 156 patients had morning GSV reflux parameters that only slightly differed from the evening parameters; this type of reflux is called a constant (unchanging) reflux. A total of 78 patients had a substantial difference between their morning and evening reflux parameters; this type of a reflux is called a situational (changing) reflux (Table II). Of the 78 patients with a situational GSV reflux, 46 had the extreme form, ie, a transient evening reflux, which only appears in the evening; these patients were classified as C0s and C0,1s and included in treatment group 1. The other 32 patients with situational reflux had a morning reflux, but with a smaller extent and duration than the reflux in the evening; these patients were classified as C2 and were included in treatment group 2. In addition, the results of the treatment were also assessed in treatment group 3, which included patients after a surgery that preserved the GSV who still had reflux according to an ultrasonography after 1 month.

Table II. Number of patients with a situational GSV reflux in

different chronic venous disease classes.

The patients in groups 1 and 3 received monotreatment with MPFF.14 The treatment guidelines included administering MPFF for 90 days (1000 mg per day). The patients in group 2, with situational GSV reflux, underwent a Muller phlebectomy15 for all dilated GSV tributaries, while preserving the GSV (n=38 lower legs).9 Multiple small phlebectomy incisions (maximum 2 mm) were made. In 19 cases, the procedures were performed under tumescent local anesthesia. In 13 patients with significant varicosities (including patients who had both limbs affected), the surgery was done under general anesthesia.

The statistical analysis was performed using the nonparametric Wilcoxon and Mann-Whitney tests. The mean values were determined along with the 95% CI.

Results

According to the morning ultrasonography results, all 106 women classified as C0s and 0,1s had no GSV reflux in the lower limbs. Evening examination showed that, in treatment group 1, 46 people (43.4%) had GSV reflux in 59 lower limbs (Table II). The evening GSV reflux was segmental (6 to 31 cm in length).

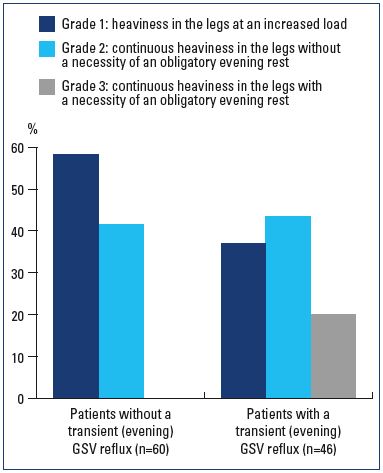

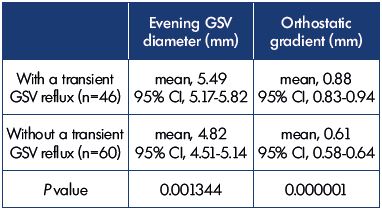

All 106 C0s and C0,1s patients had complaints of leg heaviness at the end of the day. However, patients with transient GSV reflux had more severe symptoms than did the patients without reflux (Figure 1). In the subgroup with a transient evening reflux, there was a significant difference (Table III) in the evening diameter (P=0.001344) and orthostatic gradient (P=0.000001). In the lower limbs with a transient evening reflux, the orthostatic gradient was 0.88 mm (95% CI, 0.83-0.94) and the evening GSV diameter was 5.49 mm (95% CI, 5.17-5.82). In the lower limbs without a transient evening reflux, the orthostatic gradient was 0.61 mm (95% CI, 0.58-0.64) and the evening GSV diameter was 4.82 (95% CI, 4.51-5.14).

Of the 188 examined patients with varicose veins (C2), 156 had the same GSV reflux parameters over 24 hours (extent [P=0.129083] and duration [P=0.357139]) (Table IV). In the 32 people in treatment group 2, the evening reflux parameters (reflux extent, reflux duration) differed significantly (P=0.000001) from the morning parameters (Table IV).

Figure 1. The severity of leg heaviness in patients with a transient

evening GSV reflux (n=46) or without this symptom (n=60).

Table III. The GSV parameters in patients classified as C0s and

C0,1s with a transient evening GSV reflux (n=46) or no transient

evening GSV reflux (n=60) at duplex ultrasonography and a

DOL test.

Results of the treatment

Dynamics of the GSV parameters in the classes C0s and C0,1s with a transitory evening GSV reflux with MPFF treatment

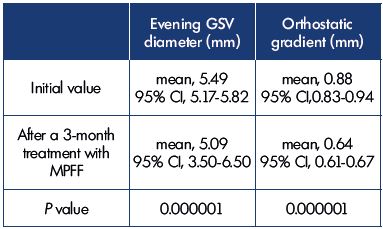

The therapeutic effect in 46 women with a transient evening GSV reflux can be seen clearly when comparing the GSV parameters before and after a 3-month MPFF treatment (Table V). The reflux was resolved in 76.1% of the women and all of them had the reflux previously located in one segment of the thigh or calf. There was a significant decrease (P=0.000001) in both the detected evening GSV diameters from 5.49 mm (95% CI, 5.17-5.82) to 5.09 mm (95% CI, 3.50-6.50) and the orthostatic gradient from 0.88 mm (95% CI, 0.83-0.94) to 0.64 mm (95% CI, 0.61- 0.67).

Table V. Comparison of the GSV parameters in patients with

a transitory evening GSV reflux before and after a 3-month

treatment with MPFF according to the duplex ultrasonography

and DOL test (n=46).

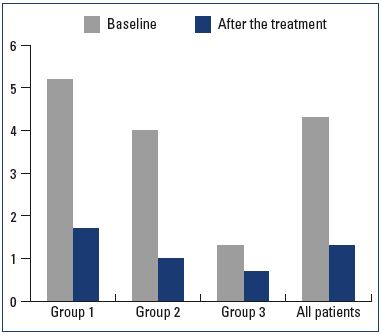

Figure 2. The severity of leg heaviness in different treatment

groups with a situational reflux before (baseline) and after the treatment according to the 10-cm visual analog scale.

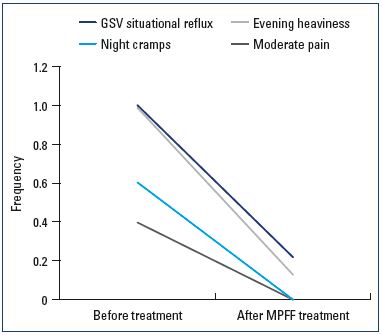

Dynamics of the clinical symptoms and the quality of life in patients with situational reflux

Initially, all 46 patients with transient reflux had complaints of evening leg heaviness, 14 had moderate pain at the end of the day, and 24 had nighttime leg cramps. After treatment with MPFF, leg heaviness disappeared in 89.3% of the patients and the symptoms decreased significantly in 10.7% of the patients. The intensity of the symptoms were reduced from 5.2 to 1.7 (P=0.000001) according to the 10-cm visual analog scale (Figure 2), pain at the end of the day disappeared in all 14 patients, and nighttime cramps resolved in all 24 patients. The global index score (CIVIQ-20) decreased from 47.16}7.93 to 25.82}9.15 after treatment (P=0.000005).

Dynamics of the GSV parameters in C2 patients with a situational GSV reflux after eliminating all varicose tributaries and preserving the GSV

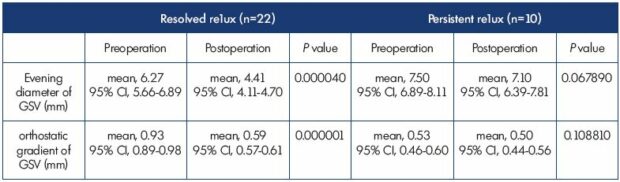

The situational reflux was eliminated in 68.8% of the limbs 1 month after surgery.22 Table VI represents a comparison of the reflux and GSV parameters. In the lower limbs with a resolved reflux, the initial orthostatic gradient decreased from 0.93 mm (95% CI, 0.89-0.98) to 0.59 mm (95% CI, 0.57-0.61) (P=0.000001) and the initial evening GSV diameter decreased from 6.27 mm (95% CI, 5.66-6.89) to 4.41 mm (95% CI, 4.11-4.70) after surgery (P=0.000001). In the lower limbs with persistent reflux, the orthostatic gradient (which was lower initially) decreased from 0.53 mm (95% CI, 0.46-0.60) to 0.50 mm (95% CI, 0.44-0.56) (P=0.108810) and the GSV evening diameter decreased from 7.50 mm (95% CI, 6.89-8.11) to 7.10 mm (95% CI, 6.39-7.81) after surgery (P=0.067890). Reducing the daily blood volume loading after a phlebectomy of the varicose tributaries preserved the muscular-tonic properties of the venous wall and provided recovery of the GSV valve function.16

Table VI. Changes in the diameter of GSV near the saphenofemoral junction in lower limbs with (n=10) or without (n=22) persistent

postoperative GSV reflux with a reflux duration >0.5 seconds before surgery and 1 month after surgery.

Dynamics of the clinical symptoms and the quality of life in patients with situational reflux

Before surgery, 91% of C2 patients with a situational GSV reflux had complaints of leg heaviness, 53.1% patients had moderate pain at the end of the day, and 71.8% had nighttime leg cramps. All 32 patients had complaints of esthetic defects associated with the varicose veins. In 1 month after the surgery, the feeling of heaviness in the legs disappeared in 89.3% of the patients and the symptoms decreased significantly in 10.7% of the patients. In general, the intensity of the leg heaviness was reduced from 4.0 to 1.0 (P=0.000005) according to the 10-cm visual analog scale (Figure 2), pain at the end of the day disappeared in all 17 patients, and nighttime cramps resolved in all 23 patients. All patients emphasized an excellent esthetic result. The global index score (CIVIQ-20) decreased from 61.17±9.69 to 34.64±8.78 after the surgery (P=0.000005).

Dynamics of the GSV parameters in C2 patients and a persistent postoperative situational GSV reflux after treatment with MPFF

All 10 patients who still had GSV reflux after surgery underwent a 3-month treatment with MPFF; the reflux was examined after MPFF treatment. After the treatment, the reflux was significantly reduced in 60% of the patients and the reflux was resolved in 40% of the patients.

Dynamics of the clinical symptoms and the quality of life in patients with situational reflux

In 1 month after surgery, all 10 patients were generally satisfied; only 2 still felt mild leg heaviness and increased tiredness. After MPFF treatment, leg heaviness decreased, but its intensity, being initially minimal, differed slightly from 1.3 to 0.7 (P=0.45632) according to the 10-cm visual analog scale (Figure 2). Also, being generally satisfied with the operation results, patients noted small changes in their quality of life. The global index score (CIVIQ-20) decreased from 50.63±7.43 to 29.33±7.18 after the treatment.

Correlation of clinical and ultrasound results of MPFF treatment

Of the patients with a situational GSV reflux, patients complained of evening heaviness in their legs (n=77), moderate pain at the end of the day (n=31), and nighttime cramps (n=47). MPFF alone for C0s, C1s patients or the combination of MPFF and an elimination of the varicose tributaries and preservation of the GSV for C2 patients, it is possible to recover an impaired GSV function in 78.2% of patients with a situational GSV reflux and to significantly improve the GSV function (ie, reflux extent and duration) in 21.8% of cases. MPFF led to the complete disappearance of leg heaviness in 87.2% of patients, and 12.8% of patients felt a significant decrease in the intensity of the heaviness. Moderate pain at the end of the day and nighttime cramps disappeared in all patients. These clinical changes occurred synchronously with the elimination of GSV reflux (Figure 3). The global index score (CIVIQ-20) decreased from 50.63±7.43 to 29.33±7.18 after the treatment.

Discussion

The research demonstrated that, in a real-world practice, there are two types of GSV reflux–constant and situational– and their reaction to the external and internal factors differs significantly. In the authors’ opinion, the proposed term “situational GSV reflux” can adequately characterize the features of the latter as its parameters vastly differ after prolonged orthostatic load compared with the parameters after sleeping. An ultrasonography with a DOL test shows the situational nature of the reflux by assessing the competence level of the muscular-tonic function of the GSV wall. With the help of DOL test, a situational GSV reflux was detected in 33.3% of the C0s, C1s, and C2 patients who visited the clinic during their daily medical practice. The differentiation of an extreme form of situational reflux–a transient evening reflux–helps describe the development of primary varicose veins.

The modified viscoelastic properties of the venous wall are a feature of primary varicose veins.17 Even the small veins have a muscular system.18 Veins play a leading role in providing the constant blood flow to the heart.19 The main pathological process of varicose veins is supposed to be myosclerosis, which arises as a result of leukocytes getting into the venous wall during the process of blood flow slowing.20 However, the destruction of the venous wall does not occur in a single step. In the first stage, a muscular-tonic dysfunction of the GSV wall occurs according to the increased creep, a basic biophysical characteristic of the veins at phlebopathy.11 Such functional insufficiency of a macroscopically unchanged venous wall due to a prolonged orthostatic load leads to transient hypervolemia in the lower limbs.21 When the volume of the drained blood and the volemic load exceed the musculartonic potential of the GSV, it will expand; moreover, it will lead to a relative valvular insufficiency. The regional venous hypervolemia occurring in some C2 patients occurs due to varicose tributaries that have already been formed due to the permanent deformation of the venous wall. At the end of the day, a bulk of the deposited blood in a limb with varicose veins is located mostly in varicose tributaries of the GSV, which form most of the superficial venous system.22

The comparison of the clinical severity of patients with or without a reflux at phlebopathy showed that, in the second case, the clinical manifestations of the disease are more pronounced. This fact points to a qualitatively new state of the venous system that arises from transient GSV reflux. This state may be a transitional stage and a binding link between simple phlebopathy (C0s) and varicose forms (C2) of chronic venous disease.

The detection of GSV reflux should not be the main indication for GSV ablation; on the contrary, the reasons for its occurrence should be understood to exclude its situational nature. For both variants of situational GSV reflux, there is a complex of therapeutic actions that may be effective without stripping or ablation of the GSV. Thus, by treating with MPFF alone for C0s and C1s patients or with the combination of MPFF and surgery to eliminate the varicose tributaries and preserve the GSV for C2 patients, it is possible to recover an impaired GSV function in 78.2% of patients with a situational GSV reflux and to improve the GSV function significantly in 21.8% of cases. Moreover, a transient evening GSV reflux should be an absolute contraindication to ablation of this central subcutaneous trunk that has no other alternative.

MPFF is a treatment that attempts to enhance venous tone.24 MPFF is an effective instrument for treating C0s and C0,1s patients and transient reflux and after a surgery for C2 patients who had an incomplete elimination of the GSV reflux. Moreover, in both cases, the main final trunk was saved. It is also vital to emphasize that 40% of patients who still had reflux after eliminating of the varicose tributaries felt improvements in their state after treatment with MPFF. The resulting normalization of the blood flow in the subcutaneous veins of the patients’ lower limbs led to a significant regression in the clinical symptoms and a vast increase in the quality of life. The data confirm that MPFF treatment is a basic multipurpose instrument that stops orthostatic hypervolemia and reduces the volemic load on the GSV in the early stages of varicose veins.

In general, the present study demonstrated that, in a daily medical practice, greater attention should be given to the early stages of varicose veins and a wider use of drug therapy. These actions will allow for the preservation of the GSV in patients classified as C0s, C0,1s, and C2. It can be hypothesized that such a treatment direction in phlebology may prospectively help decrease the number of patients with late (and severe) stages of varicose veins.

Conclusion

1. Situational GSV reflux, in which the duration and extent of the reflux differs over 24 hours due to external and internal factors, is detected in 33.3% of C0s, C1s, and C2 patients who visited the clinic during their daily medical practice.

2. The detection of GSV reflux should not be the main indication for GSV ablation, a central final subcutaneous line that has no alternative; on the contrary, the reasons for its occurrence should be understood with the help of a duplex ultrasonography and a DOL test.

3. MPFF treatment is a basic multipurpose treatment that reduces transient ortho-dependent regional hypervolemia that results from a weakening of the muscular-tonic function of the venous wall. Treatment with MPFF alone for C0s, C1s patients or the combination of MPFF and the elimination of the varicose tributaries and preservation of the GSV for C2 patients, makes it possible to recover an impaired GSV function in 78.2% of patients with a situational GSV reflux and to improve the GSV function significantly in 21.8% of cases.

4. MPFF led to the complete disappearance of leg heaviness in 87.2% of patients, and 12.8% of patients felt a significant decrease in the intensity of the heaviness. Moderate pain at the end of the day and nighttime cramps disappeared in all patients. Moreover, there was a parallel improvement in all patients’ quality of life, which was demonstrated using CIVIQ-20: the global index score decreased from 50.63±7.43 to 29.33±7.18 after treatment.

REFERENCES

1. Trendelenburg F. Ligation of the great saphenous vein in lower leg varicose veins [in German]. Beitr Klin Chir. 1891;7:195-270.

2. Bergan JJ, Schmid-Schönbein GW, Smith PD, Nicolaides AN, Boisseau MR, Eklof B. Chronic venous disease. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(5):488-498.

3. Murad MH, Coto-Yglesias F, Zumaeta- Garcia M, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the treatments of varicose veins. J Vasc Surg. 2011;53(suppl 5):49S-65S.

4. Rasmussen L, Lawaetz M, Bjoern L, Blemings A, Eklof B. Randomized clinical trial comparing endovenous laser ablation and stripping of the great saphenous vein with clinical and duplex outcome after 5 years. J Vasc Surg. 2013;58(2):421-426.

5. Pittaluga P, Chastanet S. Treatment of varicose veins by ASVAL: results at 10 years. Ann Vasc Surg. 2017;38:e:10.

6. Biemans AA, van den Bos RR, Hollestein LM, et al. The effect of single phlebectomies of a large varicose tributary on great saphenous vein reflux. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2014;2(2):179-187.

7. Atasoy MM, Oğuzkurt L. The endovenous ASVAL method: principles and preliminary results. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2016;22(1):59-64.

8. Zolotukhin IA, Seliverstov EI, Zakharova EA, Kirienko AI. Isolated phlebectomy leads to disappearance of great saphenous vein reflux. Flebologia 2016;1:8-16.

9. Tsukanov YT, Tsukanov AY. Predictive value of a day orthostatic loading test for the reversibility of the great saphenous vein reflux after phlebectomy of all varicous tributaries. Int Angiol. 2017;36(4):375- 381.

10. Tsoukanov YT, Tsoukanov AY, Nikolaychuk A. Great saphenous vein transitory reflux in patients with symptoms related to chronic venous disorders, but without visible signs (C0s), and its correction with MPFF treatment. Phlebolymphology. 2015;22(1):18-24.

11. Tsukanov YT, Tsukanov AY, Clinical assessment of phlebopathy severity by specification of leg heaviness symptom. Angiol Sosud Khir. 2003;9(1):67-70.

12. Labropoulos N, Tiongson J, Pryor L, et al. Definition of venous reflux in lower extremity veins. J Vasc Surg. 2003;38(4):793-798.

13. Engelhorn CA, Manetti R, Baviera MM, et al. Progression of reflux patterns in saphenous veins of women with chronic venous valvular insufficiency. Phlebology. 2012;27(1):25-32.

14. Lyseng-Williamson KA, Perry CM. Micronised purified flavonoid fraction: a review of its use in chronic venous insufficiency, venous ulcers and haemorrhoids. Drugs. 2003;63(1):71-100.

15. Muller R. Traitement des varices par phleebectomie ambulatoire. Phlebologie. 1966;19(4):277-279.

16. Pittaluga P, Chastanet S, Locret T, Barbe R. The effect of isolated phlebectomy on reflux and diameter of the great saphenous vein: a prospective study. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2010;40(1):122- 128.

17. Clarke H, Smith SR, Vasdekis SN, Hobbs JT, Nicolaides AN. Role of venous elasticity in the development of varicose veins. Br J Surg. 1989;76(6):577-580.

18. Caggiati A, Philips M, Lametschwandtner A, Allegra C, Valves in small veins and venules. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2006;32(4):447-452.

19. Caro CG, Pedley TJ, Schroter RC, Seed WA. The mechanics of the circulation. Oxford University Press; 1978.

20. Raffetto JD, Mammello F. Pathophysiology of chronic venous disease. Int Angiol. 2011;33(3):212-221.

21. Tsukanov YT. Local venous hypervolemia as a clinical pathophysiological phenomenon of varicose veins. Angiol Sosud Khir. 2001;7(2):53-57.

22. Caggiati A, Rosi C, Heyn N, Franceshini M, Acconcia M.C. Age-related variations of various veins anatomy. J Vasc Surg. 2006;44(6):1291-1295.

23. Tsukanov YT, Nikolaichuk AI. The case of GSV transient (evening, orthodependent) reflux in a hip going into the tributary in woman with reticular varicose veins (C1s). J Vasc Med Surg. 2015;3:219.

24. Ibegbuna V, Nicolaides AN, Sowade O, Leon M, Geroulakos G. Venous elasticity after treatment with MPFF at a dose of 500 mg. Angiology.1997;48(1): 45-49.