Differential diagnosis of chronic leg ulcers

Jasna Lipozenčić

Venereology, University Hospital

Center Zagreb and School of Medicine,

Zagreb, Croatia

ABSTRACT

Background: Chronic leg ulcers are nonhealing wounds on the distal aspects of the leg. Chronic venous insufficiency occurs when the venous system of the legs becomes inefficient and is a price we pay for our upright posture. The majority of chronic leg ulcers are caused by venous disease, but occasionally ulcers are associated with arterial problems or vessel inflammation (vasculitis).

Objective: To describe the varying dermatoses found in patients with chronic leg ulcers.

Study design: Literature search and personal experience of differential diagnoses associated with chronic leg ulcers.

Setting: Patients with chronic leg ulcers attending the Phlebology Clinic of the University Dermatology Department in Zagreb.

Methods: Determination of causes of leg ulcers through medical history, physical examination and laboratory investigations.

Results: Authors’ recommendations for a general approach to the differential diagnosis of chronic leg ulcers.

Conclusion: Leg ulcers associated with chronic venous insufficiency occur in 1% of the population in developed countries and are found in 5% of those aged 80 years or more. The correct diagnosis of the cause of leg ulceration is important as up to 20% are not of venous origin.

Establishing the etiology of a leg ulcer is important as various treatment modalities are available, but the specific treatment will be dependent on the underlying ulcer cause. Most wounds, of whatever etiology, heal without difficulty. Some wounds are subject to factors that impede healing, although healing is not prevented if the wounds are managed appropriately.1-2

This short overview on the differential diagnosis of leg ulcers considers chronic leg ulcers, ie, those present for more than 6 weeks, a condition suffered by approximately 0.2%-2% of the European population. At least half of these ulcers have an underlying venous pathology, but the figure can be as high as 80%-90%, especially when ulcers localized to the foot are excluded. The prevalence of leg ulcers increases proportionately as the population ages.1-4

Chronic venous insufficiency (CVI) of the lower extremities is a common medical problem. Sustained venous hypertension produces a cascade of pathologic events clinically graded by clinical manifestations (C), etiologic factors (E), anatomic distribution (A), and underlying pathophysiologic findings (P) – the CEAP classification of chronic venous disease. Approximately 50% of venous ulcers are a consequence of CVI of the superficial venous system (intrafascial superficial veins with or without perforator insufficiency). After venous ulcers, other common chronic leg ulcers include arterial ulcers (5%-10%) (Figures 1, 2), neuropathic ulcers caused by a combination of factors (Figures 3 a-d), and ulcers associated with skin cancers (Figure 4). Lately, an increase in the prevalence of arterial (12%) and mixed (arteriovenous) ulcers (22%) has been observed, probably reflecting aging of the population.3, 4

Figure 1. Venous ulcer

• Localization – low (distal) third of the tibia, perimalleolar

• Pain – moderate, it weakens with lying and rest

• Debridement – causes venous hemorrhage

• Bottom – abundant granulations, humid

• Edges – erythematous, inflamed, elevated, and hard

Figure 2. Arterial ulcer

• Localisation − ulcer is most frequently found in areas of bone

strain – acral parts (thumb, ankle)

• Round, with sharp edges

• Bottom of the ulcer is dry, with little or no granulations, with

present necrosis

• Deep with affected deeper structures – until tendons

• Surrounding skin is dry, cold, pale, shiny and hairless,

muscle weakening and atrophy of tibia and foot skin

Figure 3a. Vasculitis leukocytoclastica

• Vasculitis is an inflammation of the blood vessel wall and

affects a variety of organs, including the skin

• Immune complex deposition between endothelium and basal

capillary membranes and venules

• Leading to chronic inflammation and ultimately to cell death,

tissue necrosis and ulceration

• Symmetrical

Figure 3b. Polyarteritis nodosa

• Multisystemic necrotic vasculitis

• Present with general symptoms

• Affects kidneys and peripheral and central nervous systems

• Most frequent occurrence bilateral pretibia

• Most frequent skin changes are similar to “livedo racemosa”

with painful nodules, ulcerations and purpura

Figure 3c. Pyoderma gangrenosum

• Chronic ulcer − gangrenous skin affection of unknown

etiology

• Starts with occurrence of pustula

• Deep necrotic ulcer, with elevated and undetermined livid

edge

• Rapid peripheral expansion and bizarre shape

• If not treated in time it can affect deeper structures including

bone

• Mostly localised on lower limbs

• Painful

Figure 3d. Necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum

• Present in about 60% of diabetes patients

• Causative connection between necrobiosis lipoidica and

diabetic microangiopathy

• Observed as ischemic ulceration

• Symmetrical on extensor sides of tibia

• In one-third of patients ulceration occurs

• It can ulcerate after a trauma

• Yellowish ulceration, fat ulcer bases

• Heals with difficulty

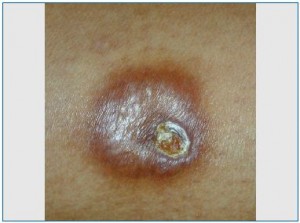

Figure 4. Basocellular carcinoma

• In most cases (sometimes as fibrosaracoma) it occurs in

chronic ulcers, especially on lower limbs

• Most probably occurs because of increased number of cell

divisions on the bottom and the surrounding area of an ulcer

• Hypertrophic granulations, indurations and hemorrhage

• On area of perforation an ulcer grows, often kidney shaped,

with sharp edges

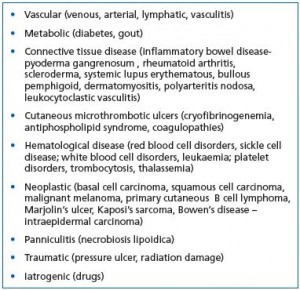

The most difficult diagnostic and therapeutic problems are encountered in patients with leg ulcers in whom the major cause of the ulcer cannot be found, though a certain degree of venous insufficiency exists. In a smaller but significant number of patients, chronic leg ulcer may be a manifestation of a variety of dermatologic, systemic and infectious diseases. The most important differential diagnoses are those defined by Lautenschlager2 with our additional modifications (Table I).

Table I. Differential diagnosis of chronic leg ulcers (from

Lautenschlager and Eichmann2 with authors modifications).

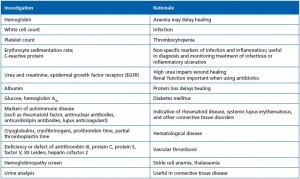

The differential diagnosis of chronic leg ulcers may be straightforward, but at times will require time, effort, and patience by both physician and patient. The search for the cause of a leg ulcer should include a detailed medical history, physical examination, evaluation of arterial and venous blood flow, and suitable laboratory tests (Table II).3,5,6

Table II. Laboratory investigations required before treating a wound3

Medical history and findings from the physical examination dictate the selection of additional investigations. Due to the many possible causes of leg ulcers, the number of potentially useful diagnostic tests is also large. Depending on the situation, microbiological tests, skin biopsy, radiologic imaging, and epicutaneous patch tests may be indicated.6 Of all the tests, biopsy is indispensable for the confirmation of vasculitides, tumors, granulomatous inflammation, and many skin infections, especially micobacterial and fungal infections. A correct sample must incorporate both the margin and base of the ulcer.6-12 If there is uncertaintly about the best place to biopsy, multiple punch biopsies can be taken from different parts of the ulcer. The decision on when to take a leg ulcer biopsy is dependent on a number of criteria, but should be considered with: typical ulcers that do not respond to standard treatment or even worsen with treatment, atypical ulcers where the cause is not venous, arterial or neuropathic ulcers (vasculitis, systemic and other dermatologic diseases), ulcers highly suspicious for malignancy (unusual localization, nodular changes, rolled borders, multiple coalescing ulcers, presence of regional lymphadenopathy), or recent travel to tropical countries.2,6

Table III. General approach to differential diagnosis of chronic

leg ulcer (authors’ recommendations).

The most useful approach to diagnose CVI is with Doppler and duplex sonography. Other procedures such as light reflection rheography (LRR), digital photoplethysmography (DPPG), and venous plethysmography (resting and dynamic) can be used as indicated. When deciding on the possibility of surgery for postthrombotic syndrome with secondary varicosities, invasive phlebodynametry (measurement of venous pressure with intravascular needle) is often required. Measurement of the ankle-brachial index (ABI) is a simple and reliable test for the assessment of arterial blood flow in the leg.6-9 Phlebography is usually not necessary when the above approaches are employed (Table III).

1. Nelzen O. Epidemiology of venous ulcers. In: Bergan JJ, Shortell CK, eds. Venous ulcers. Burlington, MA: Elsevier Academic Press;2007:27-41.

2. Lautenschlager S, Eichmann A. Differential diagnosis of leg ulcers. In: Hafner J, Ramelet A-A, Schmeller W, Brunner UV, eds. Management of leg ulcers. Current Problems in Dermatology, vol. 28. Basel, Switzerland: S. Karger AG;1999:257-270.

3. Grey JE, Enoch S, Harding KG. Wound assessment. In: Grey JE, Harding K, eds. ABC of Wound Healing. Oxford, England: Blackwell Publishing BMJ Books;2006:285-288.

4. Oien RF, Ragnarson Tennvall G. Accurate diagnosis and effective treatment of leg ulcers reduce prevalence, care time and costs. J Wound Care. 2006;15:259-262.

5. Vowden KR, Vowden P. The prevalence, management and outcome for patients with lower limb ulceration identified in a wound care survey within one English health care district. J Tissue Viability. 2009;18:13-19.

6. Raju S, Neglén P. Clinical practice. Chronic venous insufficiency and varicose veins. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:2319-2327.

7. Keen D. Critical evaluation of the reliability and validity of ABPI measurement in leg ulcer assessment. J Wound Care. 2008;17:530-533.

8. Harding KG, Morris HL, Patel GK. Healing chronic wounds. BMJ. 2002;324:160-163.

9. Singer AJ, Clark RA. Cutaneous wound healing. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:738-746.

10. Simon DA, Dix FP, McCollum CN. Management of venous leg ulcers. BMJ. 2004;328:1358-1362.

11. Izadi K, Ganchi P. Chronic wounds. Clin Plast Surg. 2005;32:209-222.

12. King B. Is this leg ulcer venous? Unusual aetiologies of lower leg ulcers. J Wound Care. 2004;13:394-396.