Endovascular approach to IVC obstruction in oncological patients

Olivier Hartung, MD, MSc, FEBVS

Department of Vascular Surgery, North University Hospital of Marseille, France

ABSTRACT

Cancer can cause inferior vena cava (IVC) obstruction. Usually, an oncologic resection is not possible and palliative treatment is needed. An endovascular procedure can be performed in most cases under local anesthesia plus sedation through a percutaneous approach. Stenting is a safe and the most effective technique and provides excellent technical and clinical success rates with immediate improvement of symptoms. Despite the short life expectancy of these patients, the technique allows

them a far better quality of life. On the other hand, treatment of venous sequalae of carcinological treatment can give good long-term results.

Introduction

Inferior vena cava (IVC) obstruction is mainly due to postthrombotic disease. It can also have other causes such as retroperitoneal fibrosis, IVC atresia or hypoplasia, and benign tumors. It can also represent a complication of cancers. In such cases, all kinds of histology can be found from renal cell carcinoma to sarcoma (IVC leiomyosarcoma but also other kinds of sarcoma), lymphoma, adenocarcinoma, and others.

All intra-abdominal primary or secondary locations of cancers can compress or even invade the IVC, even more so when these lesions are located in the retroperitoneum. But IVC obstruction can also be linked with the treatment of cancers, whether it was surgery (fibrosis, lymphocele, restenosis after grafting), radiotherapy (fibrosis) and chemotherapy (mainly after central lines insertion) or even with insertion of IVC filters. These iatrogenic complications can occur during the treatment but can also occur later.

Signs and symptoms

Signs and symptoms can present as an acute deep venous thrombosis; however, the present article focuses on chronic cases.

IVC obstruction can be asymptomatic, poorly symptomatic, or very symptomatic, depending on the severity, location, and extent of the obstruction, the speed of evolution of the tumor, and the development of collateral pathways.

The most common sign is lower-extremity edema that can be limited to the limbs but can also include thighs and even the pelvis. It can be associated with venous claudication, but all signs of the C class of CEAP (clinical-etiological-anatomical-pathophysiological classification) can be found.1 All cases of lower-limb edema in oncologic patients should have venous imaging, as emphasized by O’Sullivan.2 Wang found that 80% of women treated for uterine cervical cancer with lower-limb swelling had deep vein lesions and only 20% had lymphoedema.3

Signs are typically bilateral with or without the presence of abdominal collateral pathways (Figure 1).

In case of bilateral renal veins or suprarenal IVC involvement, renal insufficiency can develop, mainly if there is a rapid progression of the disease. Indeed, low-expansion-rate tumors leave time for the development of collateral pathways through the azygos system. Hepatic insufficiency and even Budd-Chiari syndrome can also be present, mainly when suprahepatic veins are involved.

Of course, these lesions can be associated with acute deep venous thrombosis (and in this case, a dedicated treatment associating a clot removal strategy then stenting should be proposed). Cardiac function can also be affected. In all, most patients’ quality of life is severely impaired.

Imaging

The ideal imaging technique should provide identification of the primary tumor and depict the lesion, its extension in the IVC and in the surrounding structures, and differentiate blood thrombus from tumoral thrombus. It should also look for thromboembolic complications (pulmonary embolism [PE]) and secondary localizations.

Duplex scan

A duplex scan can find signs of central obstruction (decreased flow and absence of phasicity) on the common femoral and iliac veins. IVC exploration should look for obstruction or occlusion, an abdominal mass compressing or invading the IVC and collateral pathways.

CT scan and magnetic resonance imaging

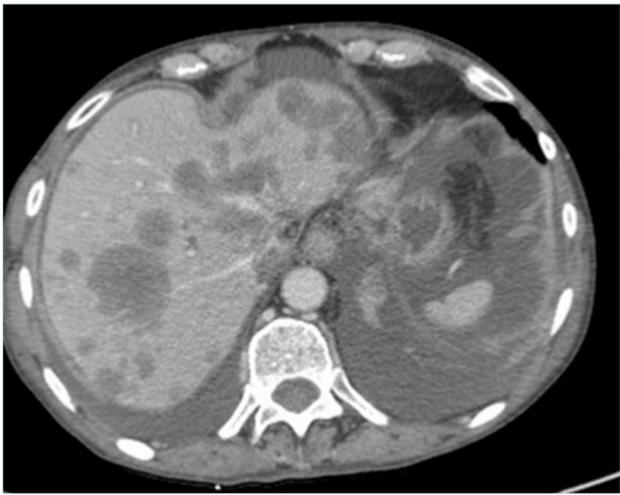

Computed tomography (CT) venography is an easily available and the most commonly used imaging technique as it can be performed through peripheral venous access with injection of 150 mL of iodinated contrast agent with acquisition at 90 and 120 seconds4 (Figures 2 and 3). According to a recent Delphi consensus, it should be the first-line imaging technique.5

Figure 2. Computed tomography (CT) scan in a patient with metastatic liver and ascites with inferior vena cava occlusion.

Figure 3. Complete occlusion of the infrarenal inferior vena cava due to lymph nodes from bladder cancer; presence of bilateral nephrostomy due to bilateral ureteral compression.

Magnetic resonance venography (MRV) is far less available but helps to differentiate neoplasic thrombus obstruction from clot5. It is performed with gadolinium enhancement, but time of flight (TOF) and phase techniques can evaluate the IVC without contrast.

Both techniques can depict the tumoral and vascular lesion(s). CT angiography and CT venography (or MRV) are mandatory in order to look for tumor vascularization, IVC status (obstruction or occlusion [Figures 2 and 3]) and collateral pathways. According to O’Sullivan, CT venography should be proposed in all cancer patients with lower-limb edema.2

Positron emission tomography scan

Positron emission tomography (PET) can identify the tumor and look for extension (lymph node, metastasis). It should be performed before any procedure in order to evaluate the prognosis.

Transesophageal echocardiography

This technique can identify the superior extension of the thrombus, mainly in case of suspected supradiaphragmatic involvement.5

Iliocavography and intravascular ultrasound

These techniques have poor usefulness preoperatively but should be used during endovascular treatment. Intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) can be used after catheterization of the lesions (after recanalization in case of complete occlusion). They help to evaluate lesion extension, neck localization, diameter, and length, and they help localize more precisely important branches such as the renal and suprahepatic veins. Moreover, after stenting, these techniques can be used to confirm the result and that stents are well expanded with a circular shape.6

Indications

According to the cause of the obstruction, different treatments can be considered in order to abolish or reduce obstruction. Whereas obstruction can sometimes be improved via radio/chemotherapy by tumor volume reduction, surgery as well as endovascular techniques can be needed.

Surgery of IVC obstruction needs in-bloc tumor resection that can include IVC. In this case, IVC reconstruction can be performed, mainly in symptomatic patients with IVC syndrome. It is indicated as a carcinological procedure but not as a palliative treatment. This surgery is invasive but can provide good results as recently reported by Mac Arthur in 167 cases.7

Treatment of venous obstruction by endovascular techniques, ie, stenting, began in the early 90’s but has expanded over the last 15 years with good long-term results. A recent review of the literature provides specific results of IVC stenting.8 In oncologic patients, endovascular techniques do not make a pretense of treating the cancer as the lesions remain in place. It can have 2 main indications: palliative treatment of obstruction or curative treatment of complications of the oncologic treatment.

Preoperative workup

Besides imaging technique, endovascular procedures do not need a specific workup as in most cases they can be performed under local anesthesia plus sedation. Indeed, these approaches and catheterization are not painful unless perforation occurs. Thus, local anesthesia plus sedation provides prevention of complications when recanalization is needed.

Preoperatively, mostly if the patient suffers lower-limb edema, an intermittent compression device should be used in order to reduce the edema and facilitate the approach on the lower limbs.

Procedure

The procedure is performed in prone position to allow multiple access possibilities in an operating or radiologic room equipped with digital subtraction angiography, echography, and IVUS.

Sedation is performed by intravenous injection of 1 mg midazolam before percutaneous approach. Then another 1 mg midazolam and 5-10 µg sufentanil are given before beginning the painful part of the procedure, ie, angioplasty and stenting. If needed, 10 mg ketamine is added. Postoperative prevention of pain is achieved via intravenous injection of 100 mg ketoprofen associated with 1 g paracetamol before the end of the procedure.

In case of IVC lesion, different points of access can be used. Most of the time, it is advisable to have bilateral lower-limb access (through the common femoral vein when lesions are limited to the IVC with or without common iliac veins, but sometimes femoral vein or even popliteal vein access can be needed) and an internal jugular vein access, mainly on the right side. Access via any of these points should be performed percutaneously under echographic guidance.

Then 6F sheaths are inserted. Catheterization can be performed using different catheters and guidewire, usually starting with a 5F vertebral catheter and a 0.035-inch hydrophilic guidewire. In some cases, mainly when recanalization is needed, smaller devices or even chronic total occlusion (CTO) crossing devices can be used.

Once the lesion is crossed (Figure 4A and 4B), super stiff or extra stiff guidewire and then a larger sheath are inserted (10-12 Fr depending on balloon and stent needs) and intravenous heparin should be given at the dose of 50 UI/kg. At this time, IVUS can be used to ensure a better evaluation of the lesion.6 Pressure gradient measurements can be performed but have value only if positive (the absence of pressure gradient can be due to collateral pathways, even more in a patient that is lying down). Then predilatation is performed using high-pressure balloons of progressive diameter mainly in case of postradiotherapy lesions (in these cases, downsizing by 2 mm in diameter compared with a standard procedure is recommended to avoid venous rupture).

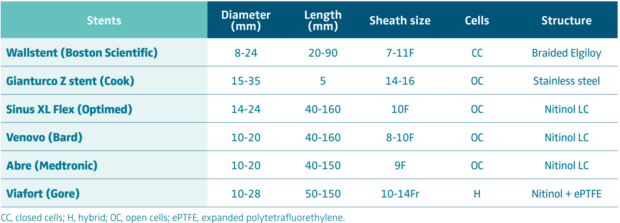

Stenting is then performed using self-expanding stents (Figure 4C and 4D). Different stents were used in the literature. Until 2010, Wallstent (Boston Scientific, Marlborough, Massachussetts, USA) and Gianturco Z stent (Cook Medical, Bloomington, Indiana, USA) were the 2 most used stents. Since the development of nitinol self-expanding stents, many others have become available, though some of them are designed for femoro-iliac veins (Venovo, Abre). Stent sizing depends not only on the diameter of the adjacent nonpathologic IVC size—that can be evaluated by CT scan or IVUS—but also to the tumor. In most cases 18 to 22 mm in diameter should be used for the IVC as larger stents can have difficulties with expanding; too-small stents can migrate and also limit flow. Few nitinol stents are available in 20-mm diameter or higher (see Table I). These stents have a more precise deployment than the Wallstent without foreshortening. Regarding stent length, they should cover at least 15 to 20 mm beyond the obstructive lesion at both ends, covering an area that goes not only from healthy-to-healthy segment but also includes a safety margin to avoid restenosis by tumor progression.9,10 When multiple stents are needed, an overlap of at least 20 mm should be used. In case of biiliocaval lesions, different stent configurations can be used: the Eiffel tower configuration while deploying the IVC stent first, then both iliac stents simultaneously (Figure 4D), or a double-barrel technique (mostly if lesions are limited to the iliocaval confluence).

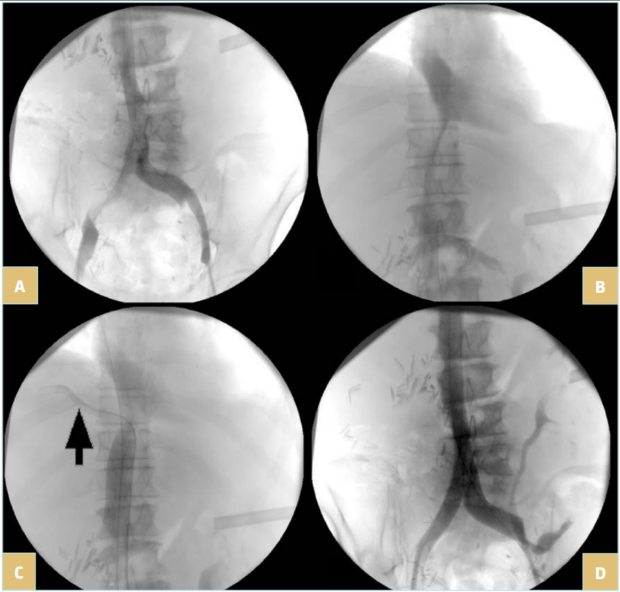

Figure 4. 76-year-old man suffering from right iliac and inferior vena cava (IVC) compression by iliac and infrarenal IVC nodes and liver metastasis from urothelial cancer with ascites (history of cystectomy and right uretero-nephrectomy): A) compression of the right iliac vein and infrarenal IVC; B) compression of the suprarenal IVC; C) after angioplasty and stenting of the suprarenal IVC; a guidewire (arrow) was positioned in the suprahepatic vein before stent deployment; D) after

biiliocaval stenting according to the Eiffel tower technique.

After postdilatation, to ensure proper expansion of the stent(s), completion IVUS is needed to check the quality of the treatment and the optimal deployment of the stent(s).6

At the end of the procedure, sheaths are removed with direct slight compression at the access site, then compressive bandages are applied. There are no indications for closing devices in veins.

Postoperative care

Intermittent compression devices are used to improve the flow and reduce the risk of thrombosis. Anticoagulation can be performed using unfractionated or low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) or even oral anticoagulation. Patients should be walking as soon as possible, most of the time when back in the ward. There is no need for a postoperative stay in the intensive care unit (ICU) after uncomplicated procedures.

Patient improvement is usually impressive. Edema persistence would call for an investigation into rethrombosis or persistent obstruction. In some cases, edema persistence can be caused by an associated lymphoedema.

Results

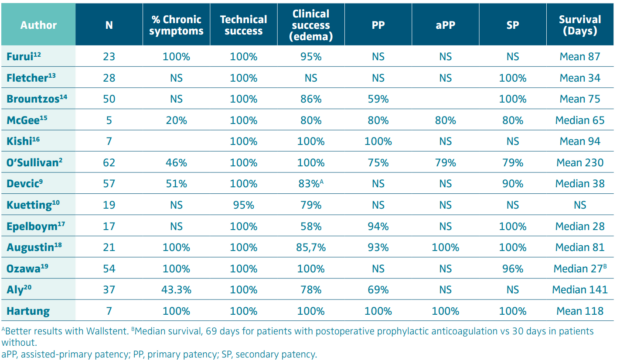

Palliative treatment

Sawada was the first in 1992 to publish on the use of stents to treat malignant IVC lesions.11 Since then, many reports have described the results. Most series report excellent technical (100%) and good clinical success on lower-limb edema and good short-term patency rates (Table II),2,9,10,12-20 but results on ascites and anasarca are far less impressive, reporting few improvements.9,14,16 A recent meta-analysis on 194 patients reported technical success, primary patency, and cumulative patency rates of respectively 100% (78%-100%), 78.5% (68%-94%), and 99% (87%-100%) with a median follow-up of 1 month (1-2.9) for malignant patients and did not differ from the whole population.8 Stenting was shown to be more efficient than chemotherapy or radiotherapy14; moreover, symptom relief is immediate after stenting, whereas it takes weeks to improve with classic oncologic treatments. As this treatment is palliative, in most cases, survival is not long with a median length inferior to 6 months in all series but one (Table II). Thus, the goal of this treatment is to improve, usually immediately, the quality of life of the patients until their death. According to Augustin18, factors of death seem to be the absence of subsequent radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy, the length of stented vein, and the involvement of the intrahepatic segment.

A phase 2 trial (28 patients, 42% IVC) and then a phase 3 randomized controlled trial (RCT; 32 patients, stenting versus medical therapy, 43% IVC) were reported by Takeuchi to treat vena cava syndromes.21 The phase 2 trial on 19 patients (enrolment stopped based on interim analysis) found technical success in 100%, clinical success in 67.9%, with 14.3% of adverse events. The RCT found a significant superiority of stenting regarding symptoms and the physical summary of an 8-item short-form health survey (SF-8) (for IVC only) without differences regarding adverse events and survival.

Regarding the type of stent, self-expanding stents are most often used. Different stents were used in the literature, from the Wallstent and the Z-stent to dedicated venous nitinol stent, for which deployment is very precise without significant shortening. Closed-cell stents have better radial force and chronic outward force resistance, properties that are of interest in that indication. Covered stents were proposed for the treatment of superior vena cava syndrome (SVCS), and according to Gwon22 patency rates seem to be superior to those of bare stents. Moreover, in case of intraluminal development of the tumor, covered stents should reduce the risk of emboly of malignant material during the procedure and later tumor progression between the struts.9,22 Bare stents, on the other hand, preserve flow from the side branches and should be less prone to rethrombosis in the IVC, mainly in patients with contraindication to anticoagulants.

IVC stenting of course is associated with a decrease in IVC pressure caudal to the obstruction9,16,17; however,according to Kishi, IVC stenting is also associated with an increase in diuresis, with edema and ascites improvement an established correlation between these criteria.16 This can induce hyponatremia. He also noted an improvement in serum creatinine, blood urea nitrogen, serum creatinine, lactate dehydrogenase, fibrinogen and platelets count. Cardiac monitoring should be carried out as the increase in caval return can provoke cardiac overload. According to Brountzos,14 preoperative elevated total bilirubin is associated with poor improvement but should not contraindicate the procedure.

Prandoni showed that patients with cancer and venous thrombosis have higher risk of rethrombosis but also of bleeding complications during anticoagulant treatment.23 Despite this, postprocedural anticoagulation is mandatory after stenting in these patients24: in a series of 30 nonthrombotic cases, primary patency rates at 12 months were 69.8% in patients with anticoagulants versus 33.3% in those without, and 3.3% of major bleeding occurred in the anticoagulated patients (self-limited retroperitoneal hematoma).

Placement of stents in front of the ostia of the renal veins did not lead to acute renal failure because these patients already have collateral pathways through the azygos system, as already described for nonmalignant lesions by O’Sullivan.25 In case of lesion of the suprahepatic IVC, it was proposed to use a bridging technique with stenting from the IVC to the SVC.26-28

Reported complications included stent shortening (mainly with the Wallstent), migration or dislocation, vein rupture, loss of patency, and restenosis; however, these are rare, certainly due to the short survival, thus few reinterventions are needed. Evaluation included a hybrid score mixing the imaging description of the lesions and clinical evaluation.

A special mention must be made of the Wu publication29 that retrospectively compared stenting (38 patients) with stenting that was associated with a linear radioactive I125 seeds strand (19 patients) placed between the stent and the venous wall, even if they mixed different anatomic lesions (brachiocephalic vein–SVC in 24 patients and IVC–iliac and femoral veins in 33 patients). Patients receiving stents plus I125 had significantly better patency rates and a better Karnofsky Performance Status score at 1 and 6 months but no significant difference in survival even if it was higher in patients receiving I125 strands (155 vs 98 days). This technique provides continuous brachytherapy to surrounding tumor tissues thus decreasing the risk of complications due to stent compression by tumor growth or intraluminal development between the struts of the stent.

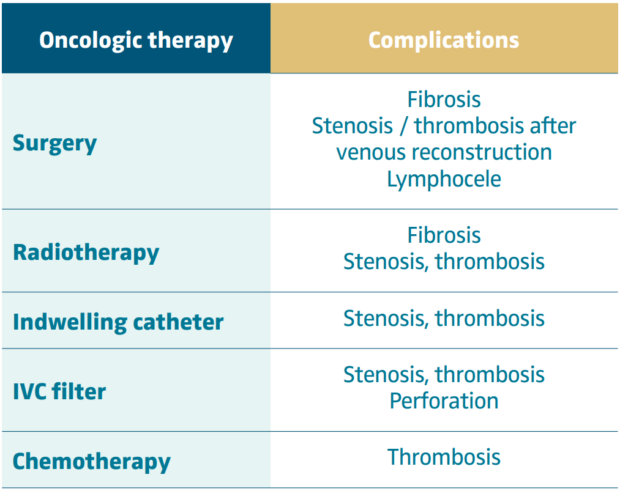

Treatment of late complications after oncologic treatment

In these cases, venous obstruction is not due to tumoral compression but to sequelae of the treatment and can have different etiologies (Table III). The main issue is to diagnose the presence of venous obstruction as emphasized by O’Sullivan.2

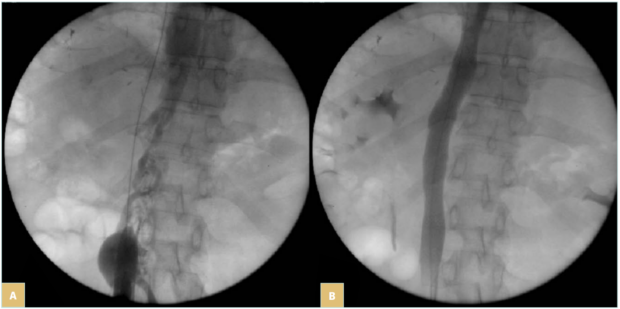

In these patients, prognosis mainly relies on the oncologic status and can be excellent when the cancer is cured (Figure 5). Therefore, results of stenting in terms of clinical outcome and patency rates should be comparable to nonmalignant lesions.

Figure 5. 44-year-old man suffering from symptomatic inferior vena cava (IVC) (lower-limb edema) occlusion due to retroperitoneal fibrosis occurring after liver tumor resection: A) IVC occlusion; B) result after recanalization and stenting with 2 Wallstents of 16 mm in diameter. Patient remained asymptomatic at 108 months of follow-up.

Literature is very scarce on this specific topic, and reports focus mainly on complications of the iliac veins but some cases are certainly included in series on venous stenting for active cancer. Brechtel reported 1 case of anastomotic stenosis after surgical bypass on the IVC during reconstruction for hepatic tumor that was successfully treated by stenting.30 Murakami reported 1 case of retroperitoneal fibrosis after radiotherapy for uterine cervical cancer with good result after IVC stenting.31 In our experience, we treated 7 patients with late complications of cancer treatment (2 postoperative retroperitoneal fibrosis, 3 had previous lymph node resection and subsequent radiotherapy, 1 radiotherapy, 1 anastomotic stenosis after surgical IVC reconstruction for leiomyosarcoma). All had successful stenting and secondary patency was 100% after a mean 81-month follow-up (26-212 months).

Conclusion

IVC obstruction due to cancer is very often out of the range of efficient carcinological treatment such as surgery. Most of the time, the treatment is palliative: endovascular procedures help these patients to have a better quality of life through a safe minimally invasive endovascular procedure with good technical and patency results and immediate clinical improvement, at least for edema; however, their life expectancy is short. Late complications of the carcinological treatment can occur in these patients and can also be treated by stenting.

CORRESPONDING AUTHOR

Olivier Hartung

Service de Chirurgie Vasculaire, CHU Nord, Chemin des Bourrelly, 13915 Marseille Cedex 20, France.

email: olivier.hartung@ap-hm.fr

Dr Olivier Hartung received an honorarium from Servier for the writing of this article.

References

1. Lurie F, Passman M, Meisner M, et al. The 2020 update of the CEAP classification system and reporting standards. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2020;8:342-352.

2. O’Sullivan GJ, Waldron D, Mannion E, Keane M, Donnellan PP. Thrombolysis and iliofemoral vein stent placement in cancer patients with lower extremity swelling attributed to lymphedema. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2015;26:39-45.

3. Wang PL, Cheng YB, Kuerban G. The clinical characteristic differences between thrombosis-related edema and lymphedema following radio-therapy or chemoradiotherapy for patients with cervical cancer. J Radiat Res. 2012;53:125-129.

4. Chaudhary RK, Nepal P, Kumar S, et al. Imaging of inferior vena cava normal variants, anomalies and pathologies, Part 2: Acquired. SA J Radiol. 2023;27:2694.

5. Balaz P, Whitley A, Heinola I, Garguilo M, Vikatmaa P; OVS Collaborative Author Group. Surgical management of tumours invading the inferior vena cava: a Delphi consensus document. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2025;70:389-399.

6. Gagne PJ, Tahara RW, Fastabend CP, et al. Venography versus intravascular ultrasound for diagnosing and treating iliofemoral vein obstruction. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2017;5:678-687.

7. MacArthur TA, Mendes BC, Colglazier JJ, et al. Early and late outcomes of patients treated with graft replacement of the inferior vena cava for malignant disease: a single center experience over three decades. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2025:102326.

8. Morris RL, Jackson N, Smith A, Black SA. A systematic review of the safety and efficacy of inferior vena cava stenting. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2023;65:298-308.

9. Devcic Z, Techasith T, Banerjee A, Rosenberg JK, Sze DY. Technical and anatomic factors influencing the success of inferior vena caval stent placement for malignant obstruction. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2016;27:1350-1360.

10. Kuetting D, Thomas D, Wilhelm K, Pieper CC, Schild HH, Meyer C. Endovascular management of malignant inferior vena cava syndromes. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2017;40:1873-1881.

11. Sawada S, Fujiwara Y, Koyama T, et al. Application of expandable metallic stents to the venous system. Acta Radiol. 1992;33:156-159.

12. Furui S, Sawada S, Kuramoto K, et al. Gianturco stent placement in malignant caval obstruction: analysis of factors for predicting the outcome. Radiology. 1995;195:147-152.

13. Fletcher WS, Lakin PC, Pommier RF, Wilmarth T. Results of treatment of inferior vena cava syndrome with expandable metallic stents. Arch Surg. 1998;133:935-938.

14. Brountzos EN, Binkert CA, Panagiotou IE, Petersen BD, Timmermans H, Lakin PC. Clinical outcome after intrahepatic venous stent placement for malignant inferior vena cava syndrome. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2004;27:129-136.

15. McGee H, Maudgil D, Tookman A, Kurowska A, Watkinson AF. A case series of inferior vena cava stenting for lower limb oedema in palliative care. Palliat Med. 2004;18:573-576.

16. Kishi K, Sonomura T, Fujimoto H, et al. Physiologic effect of stent therapy for inferior vena cava obstruction due to malignant liver tumor. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2006;29:75-83.17. Epelboym Y, Stecker MS, Fan CM, Killoran TP, Rabkin DJ, Schenker MP. Treatment of malignant inferior vena cava obstruction with Gianturco-Rosch-Z stents: a single center 13-year experience. Clin Imaging. 2020;59:95-99.

18. Augustin AM, Lucius LJ, Thurner A, Kickuth R. Malignant obstruction of the inferior vena cava: clinical experience with the self‑expanding Sinus‑XL stent system. Abdom Radiol. 2022;47:3604-3614.

19. Ozawa M, Sone M, Sugawara S, et al. Necessity of prophylactic anticoagulation therapy following inferior vena cava stent placement in patients with cancer. Interv Radiol. 2023; 8:70-74.

20. Aly AK, Moussa AM, Chevallier O, et al. Iliocaval and iliofemoral venous stenting for obstruction secondary to tumor compression. CVIR Endovasc. 2024;7:33.

21. Takeuchi Y, Arai Y, Sone M, et al. Evaluation of stent placement for vena cava syndrome: phase II trial and phase III randomized controlled trial. Support Care Cancer. 2019;27:1081-1088.

22. Gwon DI, Ko GY, Kim JH, et al. Malignant superior vena cava syndrome: a comparative cohort study of treatment with covered stents versus uncovered stents. Radiology. 2013;266:979-987.

23. Prandoni P, Lensing AWA, Piccioli A, et al. Recurrent venous thromboembolism and bleeding complications during anticoagulant treatment in patients with cancer and venous thrombosis. Blood. 2002;100:3484-3488.

24. Drabkin MJ, Bajwa R, Perez-Johnston R, et al. Anticoagulation reduces iliocaval and iliofemoral stent thrombosis in patients with cancer stented for nonthrombotic venous obstruction. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Dis. 2021;9:88-94.

25. O’Sullivan GJ, Lohan DA, Cronin CG, Delappe E, Gough NA. Stent implantation across the ostia of the renal veins does not necessarily cause renal impairment when treating inferior vena cava occlusion. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2007;18:905-908.

26. Taylor JD, Lehmann ED, Belli AM, et al. Strategies for the management of SVC stent migration into the right atrium. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2007;30:1003-1009.

27. Okamoto D, Takeuchi Y, Arai Y, et al. Bridging stent placement through the superior vena cava to the inferior vena cava in a patient with malignant superior vena cava syndrome and an iodinated contrast material allergy. Jpn J Radiol. 2014;32:496-499.

28. Zander T, Caro VD, Maynar M, Rabellino M. Bridging stent placement in vena cava syndrome with tumor thrombotic extension in the right atrium. Vasc Endovascular Surg. 2021;55:69-72.

29. Wu B, Yin G, He X, et al. Endovascular treatment of cancer-associated venous obstruction: comparison of efficacy between stent alone and stent combined with linear radioactive seeds strand. Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2020;54:565-572.

30. Brechtel K, TepeG, Heller S, et al. Endovascular treatment of venous graft stenosis in the inferior vena cava and the left hepatic vein after complex liver tumor resection. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2009;20:264-269.

31. Murakamia N, Araib Y, Takagawaa Y, et al. Inferior vena cava syndrome caused by retroperitoneal fibrosis after pelvic irradiation: a case report. Gynecol Oncol Rep. 2019;27:19-21