Endovascular approach to neoplastic superior vena cava syndrome: a comprehensive review of stenting outcomes and advancements in management strategies

Syed Mohammad Habib, MBBS

College of Medicine, Sulaiman Al-Rajhi University, Al-Bukayriyah, Qassim, Saudi Arabia

Reem Ali AL-Hussain, MBBS

College of Medicine, Sulaiman Al-Rajhi University, Al-Bukayriyah, Qassim, Saudi Arabia

Abdulmajeed Hassan Alsamsami, MBBS

College of Medicine, Taif University, Taif, Saudi Arabia

Almamoon I. Justaniah, MD, FSIR

Interventional Radiology Section, King Faisal Specialist Hospital & Research Center – Jeddah, Saudi Arabia

ABSTRACT

Superior vena cava syndrome (SVCS) resulting from malignant obstruction presents significant clinical challenges requiring prompt intervention. Endovascular stenting has emerged as the primary therapeutic approach for neoplastic SVCS, demonstrating superior efficacy compared with conventional treatments. This comprehensive review synthesizes current evidence on endovascular management, analyzing technical approaches and clinical outcomes from recent systematic reviews and meta-analyses encompassing over 2249 patients. Endovascular stenting demonstrates consistently high technical success rates of 96.8% and clinical success rates of 92.8% across all-cause SVCS. Primary patency rates reach 81.5% at 1 year, declining to 63.2% at 12 to 24 months, whereas secondary patency remains robust at 76.6% beyond 24 months following salvage procedures. Complication rates remain acceptably low at 5.8%, with reintervention required in 9.1% of cases. Malignant etiology demonstrates superior primary patency compared with benign causes, with symptom relief typically achieved within 24 to 72 hours compared with weeks required for conventional chemotherapy or radiotherapy. Endovascular stenting represents the optimal first-line intervention for neoplastic SVCS, providing rapid, safe, and durable palliation. Whereas primary patency declines over time, excellent secondary patency rates support structured surveillance and reintervention protocols. Future research priorities include standardizing outcome definitions, optimizing anticoagulation strategies, and developing evidence-based surveillance protocols for long-term management of this challenging clinical condition.

Introduction

Superior vena cava syndrome (SVCS) manifests as a result of partial or complete, intrinsic or extrinsic obstruction/compression of the superior vena cava (SVC) and/or its tributaries.1,2 The spectrum of clinical manifestations in SVCS varies depending on the underlying etiology and the speed of onset, as well as the development of venous collaterals over time.3 This progression can range from minor symptoms, such as distension of neck veins, cough, and headache, to more serious manifestations, including cerebral edema, laryngeal edema, acute respiratory compromise, and mortality. Other symptoms include orthopnea, dizziness, swelling and fullness in the head and neck, and blurring of vision, which is more severe in the morning, especially after prolonged periods of recumbency during the night.4 Additional symptoms may be observed depending on the underlying cause, such as hemoptysis, dysphagia, hoarseness, lethargy, fever, weight loss, night sweats, palpable lymph nodes, in cases of an underlying malignancy.4,5 Symptoms exacerbate in supine positions, and in worst-case scenarios, the patient may be completely unable to lie flat or bend forward.

Initially, SVCS was considered a medical emergency, but a review of recent data now indicates that SVCS follows a relatively benign course and improves without any active treatment.6,7 No definitive guidelines have been established yet for the approach to SVCS and its management. Hence, it has not yet been well-defined which patients require immediate intervention and which ones require little specific treatment, although it would greatly depend on the underlying etiology.

Specific recommendations are lacking. However, a general recommendation has been made by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network and American College of Chest Physicians supporting the consideration of stent placement (SP) and/or radiotherapy (RT) for cases of superior vena cava obstruction as a result of lung cancer. The definition of management has broadened with time, now encompassing a wide array of treatment options such as RT, chemotherapy, thrombolytics, and SVC SP, which will be discussed further as part of this review for different etiologies, specifically malignant ones in a comprehensive manner.

Etiology and incidence

Literature has reported the global incidence of SVCS to range from 1 in 650 to 1 in 3100 individuals.8 A wide spectrum of etiological factors has been found responsible for the development of SVCS. The first ever case of SVCS was discovered in 1757, in a patient with a syphilitic aortic aneurysm. Schecter reviewed 274 well-documented cases as part of a review published in 1954, where about 40% of the cases were identified as a result of tuberculous mediastinitis or syphilitic aneurysm.8,9 The importance of this study was that it revealed that there were other possible etiologies of SVCS apart from syphilitic aneurysms. It is estimated that the most common etiology is malignant tumors, accounting for 60% of the cases, whereas iatrogenic causes from thrombosis or stenosis caused by central lines or medical devices account for 30% to 40% of the total cases.10 The incidence of SVCS has been observed to rise continuously due to the increase in use of catheters, pacemakers, parenteral feeding lines, central venous lines, and defibrillators.3,11 Rice et al found that 28% of all SVCS are associated with placements of intravascular catheters or devices.3,4 Whereas complications arising from these devices contribute to a significant proportion of SVCS cases, Chee et al observed that it is a rare complication affecting only about 0.1% to 3.3% of all pacemaker patients.11 Major thrombophilia and Behcet disease are also other common benign causes of spontaneous SVCS. In older adults, malignancy remains the most common cause of SVCS, with lung cancers being the most common, followed by lymphoma.3,4,12-15 Around 75% of all cases of SVCS were observed to be a result of lung cancer, and right-sided lung cancer was seen to be more prone to causing superior vena cava obstruction in contrast to the left side.14,16,17 Small cell lung cancer (SCLC) is the most common histologic type of lung cancer related to SVCS.18 Sculier et al reported that among 643 patients with SCLC, SVCS was present in 8.6% before the treatment was commenced.19 In a Cochrane review by Rowell and Gleeson, SVCS was seen present in 10% of cases of SCLC and 1.7% of cases of non-SCLC (NSCLC) at the time of diagnosis.20 Fifteen percent of cases of SVCS are a result of lymphoma.21 Perez-Soler et al conducted a study, reporting that 36 of 915 patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma presented with SVCS, and the histologic types associated were a diffuse large cell in 23 patients, lymphoblastic in 12, and follicular large cell in 1 patient.21Diffuse large-cell lymphoma and lymphoblastic lymphoma account for the majority of lymphoma-associated SVCS cases. On the contrary, Hodgkin lymphoma rarely causes SVCS.22 Cancers due to secondary metastases account for around 5% of cases of SVCS and have been observed to have a poorer prognosis.22 Patients with malignant SVCS have a generally poor prognosis with a median survival period of 101 days from the time of occurrence.23 However, the survival is not linked to the presence or absence of SVCS but to the tumor stage and subtype.24 Other notable causes of SVCS include thymomas, thyroid carcinoma, esophageal cancer, germ cell tumors, and breast cancer.14 SVCS was found in 1 of every 10 cases of breast cancer. More rarely, SVCS can manifest in patients with pleural mesothelioma, thymic carcinoma, or other primary mediastinal germ cell tumors and intrathoracic sarcomas (Figure 1).

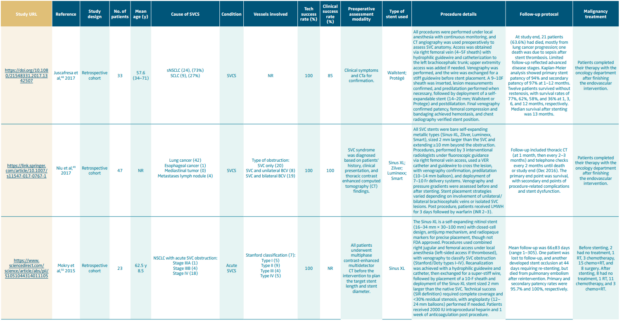

Figure 1. Malignant superior vena cava syndrome: a comprehensive overview.

The figure illustrates the comprehensive clinical spectrum of superior vena cava syndrome (SVCS). (A) Anatomy and pathophysiology: Normal SVC anatomy demonstrates venous drainage through brachiocephalic veins with collateral circulation via azygos, internal mammary, and vertebral venous systems, and obstructed SVC shows intrinsic/extrinsic compression mechanisms and compromised venous return. (B) Etiology and incidence: Global epidemiological patterns reveal malignant causes account for 60%-80% of cases, iatrogenic causes 20%-40%, and benign etiologies <5%, with global incidence ranging from 1 in 650 to 1 in 3100 individuals. (C) Malignant etiologies: Lung cancer represents 75%-80% of malignant SVCS cases, with SCLC accounting for 28%-35% of malignant SVCS (develops SVCS in ~10% of SCLC patients) and NSCLC representing 25%-30% of malignant SVCS (develops SVCS in ~2% of NSCLC patients). Lymphomas account for 10%-25% of malignant SVCS, including non-Hodgkin lymphoma (15%-25% of malignant SVCS cases) with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma being most common, while Hodgkin lymphoma rarely causes SVCS (2%-5% of malignant SVCS cases). Other malignancies represent 15%-20% of malignant SVCS, including secondary metastases from breast, testicular, and thyroid cancers, with metastatic disease

conferring poor prognosis. (D) Iatrogenic causes: Iatrogenic causes encompass various indwelling devices (central venous catheters, defibrillator leads, hemodialysis catheters, pacemaker leads, parenteral nutrition lines, port catheters), representing 20%-40% of all SVCS cases, with pacemaker-associated complications occurring in 0.1%-3.3% of patients with these devices. (E) Clinical manifestations: Clinical manifestations range from mild symptoms (neck vein distension, morning headache, cough) to moderate (facial/upper extremity swelling, dyspnea, orthopnea, dizziness, blurred vision) to severe complications (cerebral edema, laryngeal edema, acute respiratory compromise), characteristically worse in supine position with morning exacerbation. (F) Prognosis and outcomes: Prognosis shows median survival of 6-8 months for malignant SVCS with outcomes dependent on tumor stage/subtype rather than SVCS presence itself. Historical perspective shows transition from infectious etiology to malignancy-predominant pattern, with modern individualized, etiology-based treatment approaches replacing previous emergency management protocols. (G) Mainstream treatment approaches: Treatment strategies include endovascular approaches (SVC stent placement), oncological treatment (radiotherapy, chemotherapy), conservative management (position modification, diuretics, corticosteroids), and surgical interventions (SVC resection + reconstruction for primary malignant involvement, bypass reconstruction when feasible, tumor debulking for palliative cases). Modified with permission from original figure created in BioRender. Habib, SM. (2025) https://app.biorender.com/profile/template/details/t-68af2458e9155023e110f842-superior-vena-cava-syndrome-a-comprehensive-clinical-overvie. Figure link: https://app.biorender.com/profile/

template/details/t-68af2458e9155023e110f842-superior-vena-cava-syndrome-a-comprehensive-clinical-overvie NHL, non-Hodgkin lymphoma; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; SCLC, small cell lung cancer; SVC, superior vena cava; SVCS, superior vena cava syndrome.

Clinical assessment and diagnostic workup

Neoplastic SVCS commonly manifests as progressive shortness of breath, puffiness of the face and neck, venous distention, accompanied by cough and arm edema. In advanced cases, patients may exhibit stridor, laryngeal edema, or neurological manifestations secondary to cerebral venous hypertension.1,25-27 Variations in clinical presentation are determined by severity and chronicity of the obstruction, in addition to the presence and efficiency of collateral venous routes.26,28 Structures and tools, such as the Kishi symptoms score, facilitate assessment of severity and inform treatment decisions, with urgent stenting usually recommended when the scores reach or exceed 4.8,29 Early supportive measures focus on head elevation, oxygen supplementation, and airway protection when needed; the routine use of empiric corticosteroids or diuretics is no longer advised.1,25 Before intervention, patients should undergo laboratory testing including blood count, coagulation studies, renal function, particularly in patients needing contrast or anticoagulation.29 As the first-line modality, enhanced computed tomography (CT) venography is the preferred initial imaging approach, for delineating the obstruction, detecting tumor involvement, collateral circulation, and planning vascular access; for patients with contraindications to iodinated contrast, magnetic resonance (MR) venography is employed, but digital subtraction venography continues to be the gold standard, confirming anatomy and pressure gradients just before stenting.29 In stable patients, histopathologic confirmation should be obtained before oncology therapy, whereas urgent endovascular stenting may be performed to relieve symptoms prior to tissue sampling.1,25,29

Formulating a multidisciplinary management plan is crucial. One should be aware of any planned post stenting radiation, chemotherapy, or surgical debulking, as this may alter the tumor size and the degree of venous compression, which would affect the stent sizing and stability.

The endovascular approach to SVCS

Introductions

Stent implantation remains the primary acute therapeutic option for tumor-related SVCS because they bring fast relief in about 24 to 72 hours. In contrast, chemotherapy or radiation usually need a few weeks to provide benefit.30,31 More cases of benign conditions, for example catheter-related thrombosis and fibrosing mediastinitis, have been documented due to broader use of vascular devices.30

Preprocedural evaluation

Evaluation generally involves the use of contrast-enhanced CT, whereas MR imaging may be employed in selected cases; evaluation aims to assess the degree of obstructions, delineate collateral circulations, detect associated thrombosis, and measure the veins before placing the stent.31,32 Performing venography during the intervention enables real-time confirmation of the anatomical structures and lesion properties.31,32

Access strategy

The preferred method is dual access, usually femoral and internal jugular veins, which helps in crossing chronic total venous occlusions. Although upper extremity routes may also be used, the subclavian route is less often selected because of the higher risk of pneumothorax.32

Lesion’s crossing

To pass the lesion, a hydrophilic wire and an angled catheter can be used, using both antegrade and retrograde attempts when needed.32 Long sheaths and guide catheters can be used to provide stability, pushability, and stiffness to optimize the lesion’s crossing. Imaging in multiple projections with correlation to the preprocedural CT/MR may increase the success and minimize complications related to extravascular passage of the wire/catheter. If a blood clot is present, therapeutic approaches can include using a catheter or mechanical clot removal.32 Whereas anticoagulants are standard during stent insertion, long-term therapy is a matter of debate. Evidence suggests that every case must be managed individually, notably when benign and malignant present differently.

Stenting

Nowadays, dedicated venous stents are available in the market. They have different lengths, sizes, and sometimes, characteristics. The benefits of these stents are flexibility and conformity to the venous course, high radial force to maintain the vein open against external compression or recoil, large diameter and long shaft to improve flow and prevent migration. Predilation is advised to enable smooth stent positioning and improve stent expansion. In general, stenting over a stiff wire is advised. It is prudent to stent from flow-to-flow and position the tumor in the middle of the stent. Post stenting angioplasty is indicated to optimize stent expansion. In addition, intravascular ultrasound can be used to assess the stent position, patency, and proper expansion. In cases of bilateral occlusions, Y-shaped (kissing) stents can be employed. Covered stents offer potential protection from tumor ingrowth; but on the other hand, they may carry a risk of migration especially when they are undersized, and they may interfere with the collateral circulation.

Outcomes, patency, recurrence, and complication

Endovascular stenting for SVCS demonstrates high efficiency, with reported technical success and fast symptomatic relief for most patients.30-33 The primary patency rate is usually 85% to 90% in the first year, although it may fall over time, whereas the secondary patency after subsequent interventions remains high at 72% to 89%.30 Serious complications are rare, and overall complication rates remain low at 6% to 9%, including stent migration or cardiac complications.30,32,34 In cases of malignant SVCS, the survival mainly reflects tumor rather than the stent; however, stents offer rapid, lasting relief of symptoms and are more effective than medical or RT alone when immediate palliation is required.31,32,35

Comparative analysis of endovascular and other approaches

For the patient with malignant SVCS, percutaneous stent placement has emerged as the primary treatment, providing rapid relief and demonstrating excellent efficacy and safety. According to a meta-analysis of 2249 patients, the technical and clinical success was 96.8% and 92.8%, respectively. The patency rate was 90% at 1 year, and the reintervention was 9.1%, with a low complication rate of 5.8%.33 Both retrospective and prospective studies confirm these outcomes. Over a 17-year period (2006-2023), a single-center cohort study of 42 patients achieved 97.6% technical success and 91% to 93% 12-month patency, with low procedure-related mortality.36 In an additional series of 32 patients (2015-2019), the technical success was 100% and symptoms fully improved within 7 days, with only minimal complications.37 Between 1993 and 2008, a multicenter cohort (208 stents) showed prompt clinical improvement in more than 80% of patients, with excellent long-term outcomes, supporting stenting as first-line palliative intervention in malignant SVCS.38 Chemotherapy and radiation therapy provide delayed symptom relief (3 to 4 weeks), and have 46% to 80% effectiveness, with a 10% to 50% recurrence rate.7 Surgical bypass is reserved for last due to its invasiveness and morbidity.

Clinical outcomes following the endovascular intervention: pooled results of meta-analyses

Technical and clinical success rates

Endovascular stenting has demonstrated consistently high success rates across multiple large-scale systematic reviews and meta-analyses. The most comprehensive analysis encompassing 54 studies with 2249 patients over 27 years (1993-2020) reported pooled technical success rates of 96.8% (95% CI, 96.0%-97.5%) and clinical success rates of 92.8% (95% CI, 91.7%-93.8%) for all-cause SVCS.1 When analyzing malignant SVCS specifically, these rates remained similarly impressive, with 2015 patients demonstrating the reliability of endovascular intervention as a first-line therapeutic approach.1

Systematic reviews focusing on bronchogenic carcinoma-induced SVCS reported that stent insertion provided symptomatic relief in 95% of cases, significantly higher than conventional treatments such as chemotherapy and RT alone.20,26 This finding was particularly relevant for malignant etiologies, where rapid symptom resolution is often clinically imperative.20,26 Analysis specifically examining Wallstent deployment in 701 individuals with 930 stents demonstrated complete symptomatic resolution within 48 hours of intervention, with a 30-day morbidity rate of 8% and mortality rate of 3%.39 Notably, female sex was associated with higher 30-day morbidity (P<0.03), suggesting potential sex-specific considerations in patient selection and perioperative management.39

Patency outcomes and long-term durability

Patency rates represent a critical metric for evaluating the durability of endovascular interventions in SVCS management. A comprehensive meta-analysis of 39 studies involving 1539 patients revealed primary patency rates of 81.5% (95% CI, 74.5%-86.9%) up to 1-year post procedure.39 However, primary patency demonstrated temporal decline, falling to 63.2% (95% CI, 51.9%-73.1%) at 12 to 24 months post intervention.40

The distinction between primary, primary-assisted, and secondary patency becomes clinically relevant when considering long-term outcomes. At ≥24 months, primary-assisted patency reached 72.7% (95% CI, 49.1%-88.0%), whereas secondary patency achieved 76.6% (95% CI, 51.1%-91.1%).40 These findings suggest that whereas primary patency may decline over time, interventional salvage procedures can successfully maintain vessel patency in the majority of cases.40 Pooled patency remained above 90% during the first year, corroborating the findings regarding early durability.1 The Wallstent-specific analysis demonstrated long-term patency rates of 92% following successful recanalization procedures, emphasizing the salvageability of failed stents.39

Malignant versus benign etiology outcomes

The underlying etiology of SVCS significantly influences clinical outcomes and patency rates. Primary patency was significantly higher in patients with malignant stenosis compared with benign stenosis at both 1 to 3 months and 12 to 24 months post intervention.40 This finding likely reflects the different pathophysiological mechanisms underlying malignant versus benign obstruction, with malignant compression potentially responding more favorably to stent deployment.40

Differential patency outcomes based on etiology showed cumulative median patency for nonmalignant etiology reaching 550 days (interquartile range [IQR]: 14-1080) compared with 120 days (IQR: 0-925) for malignant cases (P<0.03).27 This apparent contradiction with other findings may reflect different patient populations, stent types, or measurement methodologies, highlighting the complexity of comparing outcomes across heterogeneous study populations.39 Specific analysis of benign SVCS outcomes reported identical technical and clinical success rates of 88.8% (95% CI, 83.0%-93.1%) for benign cases, which, although lower than malignant cases, still represent acceptable therapeutic outcomes.1

Complications and reintervention rates

Complication profiles vary across studies but generally demonstrate the safety of endovascular intervention. Average complication rates of 5.78% (standard deviation [SD]=9.32) across all studies were reported, with reintervention rates of 9.11% (SD=11.19).25 The relatively low standard deviations suggest consistent safety profiles across different patient populations and institutional experiences.1

Morbidity following stent insertion was greatest when thrombolytics were administered, suggesting careful consideration of adjunctive therapies.20,26 SVCS recurrence rates of 11% following stent insertion were reported, though recanalization was possible in the majority of cases, resulting in long-term patency rates of 92%.20,26 The pediatric population demonstrated higher morbidity (30%) and mortality (18%) rates, with acute complications occurring in 55% of cases.41 However, multimodal anticoagulation therapy improved outcomes by >50% (P=0.004), particularly in cases with concomitant thrombosis (present in 36% of pediatric cases).42

Prognostic factors and patient selection

Several studies identified specific factors associated with improved outcomes. Infant age (P=0.04), lack of collateral circulation (P=0.007), and presence of acute complications (P=0.005) possessed prognostic utility for outcome prediction in pediatric populations.42 The presence of collateral circulation appeared particularly important, suggesting that patients with well-developed collateral networks may have different risk-benefit profiles for endovascular intervention.42 The analysis of hepatocellular carcinoma risk in Budd-Chiari syndrome, though not directly related to SVCS stenting outcomes, provides insight into long-term complications in venous obstruction syndromes.43 Their systematic review demonstrated significant geographic variation in complication rates, emphasizing the importance of population-specific outcome data.43

Comparative effectiveness with alternative therapies

When compared with conventional therapies, endovascular stenting demonstrates superior efficacy profiles. In SCLC, chemotherapy and/or RT relieved SVCS in 77% of cases, with 17% experiencing recurrence.20,26 In NSCLC, conventional therapy achieved relief in 60% of cases, with 19% recurrence rates.20,26 These figures compare unfavorably with the 95% relief rate achieved with stent insertion and the superior long-term patency rates.20,26 The rapid symptom resolution achieved with endovascular intervention, often within 48 hours, represents a significant clinical advantage over conventional therapies, particularly in patients with severe symptoms requiring urgent decompression.39

Quality of evidence and study limitations

The grade analysis determined that the certainty of evidence for all outcomes was very low, reflecting the predominance of retrospective observational studies in this field.40 This limitation underscores the need for higher-quality prospective studies and randomized controlled trials to establish definitive evidence-based guidelines for SVCS management.40

The heterogeneity observed across studies, particularly in patency definitions and measurement time points, complicates direct comparison of outcomes. Future research should focus on standardizing outcome definitions and establishing consensus guidelines for surveillance and reintervention protocols.

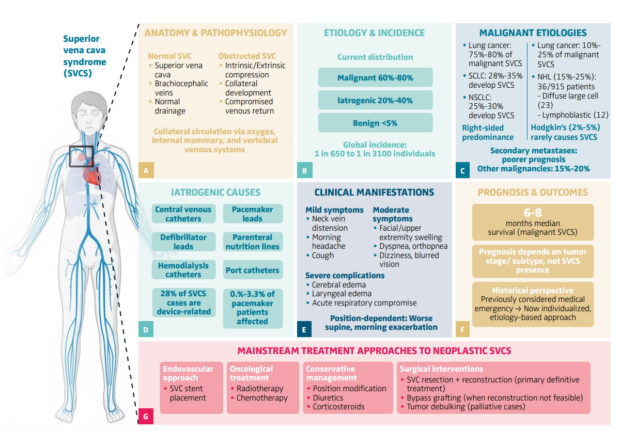

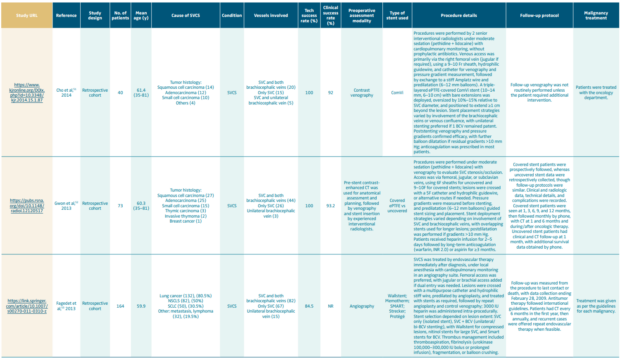

Table I provides an overview of major retrospective cohort studies evaluating endovascular treatment of superior vena cava syndrome.44-53 It provides a comprehensive overview of the causes of SVCS, technical and clinical success rates of stenting, preoperative assessment methods, stent types, procedural details, follow-up protocols, and management of the underlying malignancy. It highlights the diverse spectra of patient populations, procedural strategies, and follow-up approaches, reflecting the evolving role of endovascular stenting in SVCS management.

Table I. Summary of clinical studies on endovascular stenting for superior vena cava syndrome (SVCS).

Clinical implications and future directions

The pooled evidence strongly supports endovascular stenting as an effective first-line intervention for both malignant and benign SVCS, with high technical success rates, acceptable complication profiles, and durable medium-term patency. The ability to achieve rapid symptom resolution makes this approach particularly valuable in the management of acute or severe presentations. However, the decline in primary patency beyond the first year highlights the importance of structured surveillance programs and the need for patient counseling regarding potential reintervention requirements.40

The differential outcomes observed between malignant and benign etiologies suggest that etiology-specific treatment algorithms may optimize patient outcomes.40

Future research priorities should include prospective comparative effectiveness studies, standardization of outcome definitions, investigation of optimal anticoagulation strategies, and development of evidence-based surveillance protocols to guide long-term patient management.

Conclusions

Neoplastic SVCS, usually secondary to malignancy, demonstrates a wide spectrum of severity, ranging from mild symptoms to life-threatening complications. Endovascular stenting represents the first-line approach, delivering immediate, safe, and durable patency outcomes. When the patient is stable, histologic confirmation should be obtained before initiating oncologic therapy, where severe cases require urgent stenting. Future investigations should include harmonizing outcome measures, anticoagulation optimization, and long-term monitoring protocols.

CORRESPONDING AUTHOR

Almamoon I. Justaniah, MD, FSIR

P.O. Box 40047, Jeddah 21499, Saudi Arabia

email: ajustaniah@kfshrc.edu.sa

Dr Almamoon I. Justaniah received an honorarium from Servier for the writing of this article.

References

1. Azizi AH, Shafi I, Shah N, et al. Superior vena cava syndrome. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2020 28;13(24):2896-2910.

2. Friedman T, Quencer KB, Kishore SA, Winokur RS, Madoff DC. Malignant venous obstruction: superior vena cava syndrome and beyond. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2017;34(4):398-408.

3. Cheng S. Superior vena cava syndrome: a contemporary review of a historic disease. Cardiol Rev. 2009-;17(1):16-23.

4. Rice TW, Rodriguez RM, Light RW. The superior vena cava syndrome: clinical characteristics and evolving etiology. Medicine (Baltimore). 2006;85(1):37-42.

5. Deshwal H, Ghosh S, Magruder K, Bartholomew JR, Montgomery J, Mehta AC. A review of endovascular stenting for superior vena cava syndrome in fibrosing mediastinitis. Vasc Med. 2020;25(2):174-183.

6. Schraufnagel DE, Hill R, Leech JA, Pare JA. Superior vena caval obstruction. Is it a medical emergency? Am J Med. 1981;70(6):1169-1174.

7. Wilson LD, Detterbeck FC, Yahalom J. Clinical practice. Superior vena cava syndrome with malignant causes. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(18):1862-1869. Erratum in: N Engl J Med. 2008;358(10):1083.

8. Seligson MT, Surowiec SM. Superior vena cava syndrome. 2022 Sep 26. In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan–.

9. Schechter MM. The superior vena cava syndrome. Am J Med Sci. 1954;227(1):46-56.

10. Klein-Weigel PF, Elitok S, Ruttloff A, et al. Superior vena cava syndrome. Vasa. 2020;49(6):437-448.

11. Chee CE, Bjarnason H, Prasad A. Superior vena cava syndrome: an increasingly frequent complication of cardiac procedures. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med. 2007;4(4):226-230.

12. Breault S, Doenz F, Jouannic AM, Qanadli SD. Percutaneous endovascular management of chronic superior vena cava syndrome of benign causes: long-term follow-up. Eur Radiol. 2017;27(1):97-104.

13. Herscovici R, Szyper-Kravitz M, Altman A, et al. Superior vena cava syndrome – changing etiology in the third millennium. Lupus. 2012;21(1):93-96.

14. Ostler PJ, Clarke DP, Watkinson AF, Gaze MN. Superior vena cava obstruction: a modern management strategy. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 1997;9(2):83-89.

15. Yellin A, Rosen A, Reichert N, Lieberman Y. Superior vena cava syndrome. The myth–the facts. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1990;141(5 Pt 1):1114-1118.

16. Lochridge SK, Knibbe WP, Doty DB. Obstruction of the superior vena cava. Surgery. 1979;85(1):14-24.

17. Nogeire C, Mincer F, Botstein C. Long survival in patients with bronchogenic carcinoma complicated by superior vena caval obstruction. Chest. 1979;75(3):325-329.

18. Ahmann FR. A reassessment of the clinical implications of the superior vena caval syndrome. J Clin Oncol. 1984;2(8):961-969.

19. Sculier JP, Evans WK, Feld R, et al. Superior vena caval obstruction syndrome in small cell lung cancer. Cancer. 1986;57(4):847-851.

20. Rowell NP, Gleeson FV. Steroids, radiotherapy, chemotherapy and stents for superior vena caval obstruction in carcinoma of the bronchus: a systematic review. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2002;14(5):338-351.

21. Perez-Soler R, McLaughlin P, Velasquez WS, et al. Clinical features and results of management of superior vena cava syndrome secondary to lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 1984;2(4):260-266.

22. Gucalp R, Dutcher J, Fauci AS, et al. Oncologic emergencies. In: Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. 17th ed. New York McGraw-Hills. 2008:1730.

23. Picquet J, Blin V, Dussaussoy C, Jousset Y, Papon X, Enon B. Surgical reconstruction of the superior vena cava system: indications and results. Surgery. 2009;145(1):93-99.

24. Quencer KB. Superior vena cava syndrome: etiologies, manifestations, and treatments. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2022;39(3):292-303.

25. Grant JD, Lee JS, Lee EW, Kee ST. Superior vena cava syndrome. Endovascular Today. 2009. Accessed August 29, 2025. https://evtoday.com/articles/2009-july/EVT0709_09-php/pdf.

26. Sasikumar A, Kothiwale VA. Superior vena cava syndrome: a comprehensive review. Int J Res Med Sci. 2025;13(3):1331-1334.

27. Ponti A, Saltiel S, Rotzinger DC, Qanadli SD. Insights into endovascular management of superior vena cava obstructions. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2021;8:765798.

28. Anyagwa OE, Dairo OA, Tak RS, et al. Endovascular stenting for superior vena cava syndrome: a systematic review. Emerg Med J. 2024;9(2):154-167.

29. Wright K, Digby GC, Gyawali B, et al. Malignant superior vena cava syndrome: a scoping review. J Thorac Oncol. 2023;18(10):1268-1276.

30. Chawla S, Zhang Q, Gwozdz AM, et al. Editor’s Choice – A systematic review and meta-analysis of 24 month patency after endovenous stenting of superior vena cava, subclavian, and brachiocephalic vein stenosis. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2025;69(1):139-155.

31. Léon D, Rao S, Huang S, et al. Literature review of percutaneous stenting for palliative treatment of malignant superior vena cava syndrome (SVCS). Acad Radiol. 2022;29 Suppl 4:S110-S120.

32. Azizi AH, Shafi I, Zhao M, et al. Endovascular therapy for superior vena cava syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;37:100970.

33. Aung EY, Khan M, Williams N, Raja U, Hamady M. Endovascular stenting in superior vena cava syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2022;45(9):1236-1254.

34. Cao S, Zou Y, Lyu T, et al. Safety and efficacy of stent graft implantation for malignant superior vena cava syndrome. Heart Surg Forum. 2021;24(6):E952-E957.

35. Guerrero-Macías S, Beltrán J, Buitrago R, Beltrán R, Carreño J, Carvajal-Fierro C. Outcomes in patients managed with endovascular stent for malignant superior vena cava syndrome. Surg Open Sci. 2023;16:16-21.

36. Rioja Artal S, González Martínez V, Royo Serrando J, Delgado Daza R, Moga Donadeu L. Results of palliative stenting in malignant superior vena cava syndrome analyzing self-expanding stainless steel and nitinol venous bare metal stents. J Endovasc Ther. 2024:15266028241242926.

37. Liu H, Li Y, Wang Y, Yan L, Zhou P, Han X. Percutaneous transluminal stenting for superior vena cava syndrome caused by malignant tumors: a single-center retrospective study. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2021;16(1):39.

38. Lanciego C, Pangua C, Chacón JI, et al. Endovascular stenting as the first step in the overall management of malignant superior vena cava syndrome. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;193(2):549-558.

39. Rowell NP, Gleeson FV. Steroids, radiotherapy, chemotherapy and stents for superior vena caval obstruction in carcinoma of the bronchus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001;(4):CD001316. Update in: Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(3):CD001316.

40. Kordzadeh A, Askari A, Hanif MA, Gadhvi V. Superior vena cava syndrome and Wallstent: a systematic review. Ann Vasc Dis. 2022;15(2):87-93.

41. Sheth S, Ebert MD, Fishman EK. Superior vena cava obstruction evaluation with MDCT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010;194(4):W336-W346.

42. Nossair F, Schoettler P, Starr J, et al. Pediatric superior vena cava syndrome: an evidence-based systematic review of the literature. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2018;65(9):e27225.

43. Ren W, Qi X, Yang Z, Han G, Fan D. Prevalence and risk factors of hepatocellular carcinoma in Budd-Chiari syndrome: a systematic review. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;25(7):830-841.

44. Irace L, Martinelli O, Gattuso R, et al. The role of self-expanding vascular stent in superior vena cava syndrome for advanced tumours. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2021;103(4):296-301. 119

45. L McDevitt J, T Goldman D, J Bundy J, et al. Gianturco Z-stent placement for the treatment of chronic central venous occlusive disease: implantation of 208 stents in 137 symptomatic patients. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2021;27(1):72-78.

46. Karakhanian WK, Karakhanian WZ, Belczak SQ. Superior vena cava syndrome: endovascular management. J Vasc Bras. 2019;18:e20180062.

47. Anton S, Oechtering T, Stahlberg E, et al. Endovascular stent-based revascularization of malignant superior vena cava syndrome with concomitant implantation of a port device using a dual venous approach. Support Care Cancer. 2018;26(6):1881-1888.

48. Juscafresa LC, Bazo IG, Grochowicz L, et al. Endovascular treatment of malignant superior vena cava syndrome secondary to lung cancer. Hosp Pract. 2017;45(3):70-75. https://doi.org/10.1080/21548331.2017.1342507

49. Niu S, Xu YS, Cheng L, Cao C. Stent insertion for malignant superior vena cava syndrome: effectiveness and long-term outcome. Radiol Med. 2017;122(8):633-638.

50. Mokry T, Bellemann N, Sommer CM, et al. Retrospective study in 23 patients of the self-expanding sinus-XL stent for treatment of malignant superior vena cava obstruction caused by non-small cell lung cancer. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2015;26(3):357-365.

51. Cho Y, Gwon DI, Ko GY, et al. Covered stent placement for the treatment of malignant superior vena cava syndrome: is unilateral covered stenting safe and effective? Korean J Radiol. 2014;15(1):87-94.

52. Gwon DI, Ko GY, Kim JH, Shin JH, Yoon HK, Sung KB. Malignant superior vena cava syndrome: a comparative cohort study of treatment with covered stents versus uncovered stents. Radiology. 2013;266(3):979-987.

53. Fagedet D, Thony F, Timsit JF, et al. Endovascular treatment of malignant superior vena cava syndrome: results and predictive factors of clinical efficacy. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2013;36(1):140-149.