III. Shortcuts from the training session: “Introduction to effective medical writing”

Françoise Pitsch

Servier International, Suresnes, France

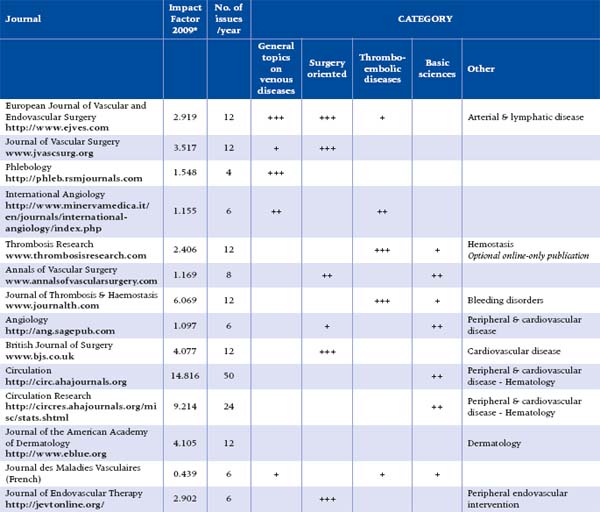

There are many journals in the field of phlebology. Some are aimed primarily at vascular surgeons treating patients with arterial, venous, and lymphatic diseases; others deal more with basic research or focus on specific areas (thromboembolic diseases, investigations in venous diseases, etc.). Depending on the type of manuscript you intend to submit, select the journal carefully. Before submission, read the instructions for authors. Complete information for authors and editorial policies are available on journal web sites. Below is a non-exhaustive list of journals indicating their subject matter, impact factors, and Web site addresses.

Good luck with your submission.

Sarah Novack

Servier International, Suresnes, France

The journal impact factor is widely used as a means to assess the impact of scientific journals, and is often interpreted as an index of quality. But how should it really be interpreted?

Journal impact factors are produced by the Journal Citation Reports from data published by the Science Citation Index (part of the ISI Web of Science®). The Science Citation Index includes more than 6500 journals, with 19 000 new articles added every week. It covers disciplines throughout the physical and life sciences. There are over 150 categories within medicine alone, including general medicine, peripheral vascular disease, and surgery. For each article in the database, the Science Citation Index produces citation data, ie, counts of the number of times the article subsequently appeared in the reference lists of other articles.

How is the impact factor calculated?

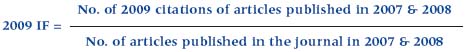

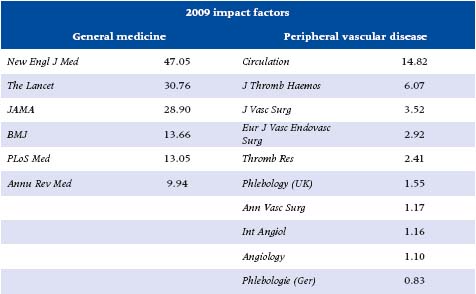

A journal’s impact factor is the ratio of the total number of citations of articles published by the journal in the two previous years to the number of articles published in the same two years (Figure 1). The 2009 impact factors appeared in the summer of 2010. The highest impact factors in medicine are found for the general journals, such as the New England Journal of Medicine, The Lancet, and JAMA (Table 1).

Figure 1. Formula for the calculation of the 2009 impact factor (IF) of a journal.

To simplify, the impact factor for 2009 could be regarded as the average number of citations an article published in the journal in 2007 or 2008 could expect to have in 2009. This means that an article with 15 citations or more per year in Circulation could be considered to have had a positive effect on the impact factor of the journal. This should be weighed against the observation that about 80% of the impact factor is determined by around a fifth of the articles in the journal.

Table 1. Selected impact factors from the Science Citation Index 2009.

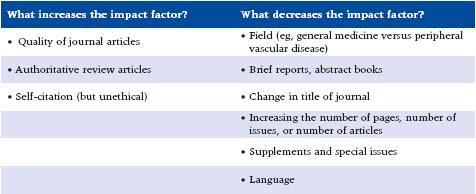

What affects the impact factor?

There are a number of features of journals that can affect impact factors, above and beyond the quality of the articles it contains (Table 2). Journals in the field of peripheral vascular disease are lower than in general medicine (Table 1), simply because the domain is smaller, and therefore there are fewer articles with fewer citations. Field is therefore fundamental to the magnitude of the impact factor: the larger the field, the higher the impact factor. A striking example of this is that a typical impact factor in fundamental life science is between 3 or 4, while in mathematics it is 0.4.1 Clearly, this does not imply that the quality of research in fundamental life science is eight times better than that in mathematics. The difference is simply a question of the size of the field.

Similarly, journals publishing a large number of review articles have higher impact factors, since such articles are more frequently cited. On the other hand, journals that publish abstracts of presentations at conferences or proceedings, which are less well cited, can expect to have lower impact factors. Other factors that may affect journal impact factors include self-citation, which is unethical if it is done with the sole of aim of increasing the impact factor. Any major change in the journal, for example, a change in the journal title, an increase in the number of pages, articles, or issues, or publication of a special issue, may have a detrimental effect on the impact factor.

Perusal of the impact factors also highlights just how important it is to publish international studies in English. English-language journals systematically have higher impact factors. This is not to discourage publication in local or national society journals. Indexation in the Science Citation Index should be regarded as a positive feature of a local journal and it is vital to support such institutions. Publishing in the author’s mother tongue can also improve information and continuing medical education in his or her country. On the other hand, results from international trials or other international projects should always be published in English in international journals for wider dissemination of research.

Table 2. What affects the impact factors?

Who uses the impact factors?

Impact factors are used by authors to help select a journal for publications. They help publishers assess and market their journals, and also libraries manage acquisitions. Another potential application is the assessment of individual researchers, for instance, by counting the number of articles in high impact factor journals. This has been the source of considerable debate, and has led specialists in bibliometrics to design new indices to measure performance.

Is there an impact factor for people?

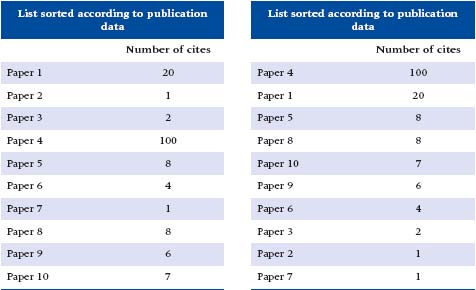

The Hirsch (h) index is a new index that can be calculated within the Science Citation Index. The h index is becoming a reference in the assessment of quality of individual scientists and researchers, much like the impact factor for journals. The h index considers the distribution of the number of citations of articles by a researcher. The general definition is as follows: the Hirsch index will be h if h of the researcher’s papers had at least h citations each.2 This can be understood through a couple of examples. First, consider a researcher with 10 articles published over 15 years and count the number of citations for each article (see example in Figure 2). If we then sort the list of articles according to the number of citations, then we see that 6 of the articles in our example have been cited 6 times or more. The h index of this fictitious researcher is therefore 6. On the other hand, if we consider a much more active researcher with 200 articles published over the last 15 years. If 50 of these 200 articles were cited 50 times or more, then this particular author would have an h index of 50.

Figure 2. The h index explained: if a researcher has 10 articles published over 15

years (left), and 6 of them have been cited 6 times or more (right), then his or

her h index would be 6.

The advantage of the h index is that it is not affected by one paper with many citations, and thus constitutes a better measure of influence than simply counting citations or number of papers. Like the impact factors, h is field-specific, and will be affected by self-citation, authoritative review articles, and multiple author papers. It may deemphasize authors who have had one or two very influential articles, for instance, the researcher in Figure 2 had one very highly cited article (100 citations) but a relatively low h index. Finally, a single number cannot give more than a rough estimate of an individual’s profile, and the h index should always be interpreted alongside other knowledge of the individual.

Conclusion

The journal impact factors and the h index are widely regarded as good measures of quality in scientific research—they are certainly the only ones we have. However, they are undoubtedly influenced by a variety of factors beyond the quality of the research published in the scientific literature. This had led to much debate in recent years,3 and to increasing efforts to find new complementary methods of evaluating journals and researchers. One option is the use of other databases, such as Google Scholar® or Scopus®, both of which provide the opportunity to count citations or the impact of an article. Bibliometric studies comparing the three databases indicated qualitatively and quantitatively different number of citations from the three databases.4 For the time being, the impact factors should be used alongside knowledge of the journal, in terms of the studies it publishes and the quality of the editorial board, for the best selection of target journals for submission of manuscripts in science.

References

1. Brown H. How impact factors changed medical publishing—and science. BMJ. 2007;334:561-564.

2. Hirsch JE. Does the H index have predictive power? Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:19193-19198.

3. The impact factor game. It is time to find a better way to assess the scientific literature. PLoS Med. 2006;3:707-708.

4. Kulkarni AV, Aziz B, Shams I, Busse JW. Comparisons of citations in Web of Science, Scopus, and Google Scholar for articles published in general medical journals. JAMA. 2009;302:1092-1096.

Victoria Lloyd

Servier International, Suresnes, France

Why use figures?

In a page of text the eye is drawn to those things that stand out—first to the titles in bold text, and then to the illustrations, which make the page more interesting, and therefore easier to read. They serve a useful purpose in presenting data in a way that is easily understandable, and in giving information an importance that would be lost in the body of the text.

Before you start to create your illustration you need to decide why? What information do you want to present? Do you need a table or a figure? What shape will it fill in the article—a portrait shape in one column or a landscape format over two or more columns? You need to think about this before submission, as afterwards it will be too late—the editor will have full control.

What tools should you use? Of course this depends on what you have available and what you feel at ease with—PowerPoint is good for drawing shapes, Excel is a good choice for data, Word is a clumsy tool for illustration. There are also professional software packages such as CorelDraw and Illustrator. All these programs can be used to cut, resize, and post illustrations into Word (embedded such that they cannot be edited by someone else).

When creating your illustration, try to avoid common mistakes concerning the following subjects:

Typeface choice

Among four basic different typefaces, there exist sans serif types such as Arial or Helvetica (a clear no-nonsense font good for titles and captions); serif typefaces such as Times or Century (classic typefaces that are easy to read and good for body copy, and also numerals, as there is less likelihood of a number one being mistaken for a lower-case “l”).

Typewriter faces and scripts are not good choices as they are inappropriate and look unprofessional.

Use only one typeface and use different weights and styles (bold and italic) for emphasis.

Letter sizing

Often too small or too big—test the size of your text by simply resizing it to the final format and printing it out to see how it reads. Keep your letter sizing consistent from figure to figure. For example, use 10-point text for the titles, 8-point for the body text. Use the variations in weight and style logically, important information in bold type, but don’t go wild.

Scale

Try and create all your figures the same size, so that when they are resized for print there will be no unpleasant surprises. Ensure that the text is readable and that there are no glaring variations in type size.

Color

Think twice before you use color—you need first of all to know if the journal for which your article is intended accepts color (it might simply print in black and white) and if it does will it charge you for the extra costs incurred? When using color photos, will they reproduce in monochrome?

Where possible, use shades of gray and the contrast of black and white to make your illustrations both interesting and easy to reproduce. Another point to consider is that if you create your illustrations in color (or use color photos) the journal might simply print them in black and white, and you will have no control over the final result.

Does the journal for which your article is intended simply print in black and white? Or does it accept color? And if it does will it charge you for the extra costs incurred?

Spelling

Use the spell-checker. It helps you to correct mistakes as they happen, and to check the final result—nothing is so unprofessional as a spelling mistake.

Finally, whatever your choices, keep everything uniform. Create your figures in the same style, using the same typefaces in the same styles and weights, at the same size, so that they can all be resized by the same amount. Ensure that the axes on your graphs are always in the same position; ensure continuity with your figures by, for example, using “X” for drug and “P” for placebo in each figure.

If in doubt, refer to the American Medical Association Manual of Style for the best way to create graphs, flowcharts, and tables.

Illustrations work better when in each case the information has been clearly structured with the eye being drawn through from the start to the end in a logical flow; black and white and gray provide both contrast and emphasis where needed and are easy to reproduce; type sizes, styles, and weights are kept to the minimum consistent with ease of understanding.

Illustration matters because the figures you use in your articles are the key to the presentation of your results. They should be one of the first choices you make when you start your article as the results you choose to illustrate have an effect on the structure of your article.

Which figure works best? The left one or the right one?

In short, good figures mean clearer presentation of key results which means a better chance of article acceptance.

David Marsh

Servier International, Suresnes, France

We’ve all felt this from time to time. Some of you may even be thinking it right now. But why, you may wonder, in an article on editing, have I used this quote (from the play “No Exit” by Jean-Paul Sartre)? Because it allows us to segue smoothly into the arcane world of the editor. Yes, that nameless individual empowered to fashion a readable article from your decent/passable/ imperfect/abysmal (delete as applicable) prose. Why, you may be wondering, should you care about this faceless person behind a desk along some dimly lit corridor? Two reasons. First, because the editor is to be respected and looked up to. Stephen King said it best: “To write is human, to edit is divine.” Second, and here we revert to the commonplace concerns of everyday life, because the editor has the power to send you scurrying back to your computer to rewrite your manuscript. Again. And again.

So you would be well advised to put yourself in the editor’s shoes, to try to understand the work of editing a manuscript. What is the editor thinking over that first coffee of the day, as your manuscript arrives on the desk? I would suggest it may be something along the lines of “Hell is other people’s prose.”

The moral then of this story is: Don’t make the editor’s life hell. That way you increase your chances of publication. So, how can you make the editor happy? The answer, surprisingly, has been around for 2500 years, albeit in a different guise: the Buddha’s Noble Eightfold Path to Enlightenment. Or at least to a better manuscript.

What is the first step on this eightfold path? Avoid wordiness. An editor’s life is too short to wade through pages of turgid prose. Be concise. After all, as Shakespeare wrote (Hamlet, Act 2, Scene 2), “Brevity is the soul of wit.” Here’s an example. An inspiration in fact—Victor Hugo. It may seem perverse to turn to this 19th century French writer as a model of brevity. After all, didn’t he rack up 500 pages in Notre-Dame de Paris (The Hunchback of Notre-Dame) and a staggering 1200 in Les Misérables? So how can we speak of conciseness and Victor Hugo in the same breath? Bear with me. It all comes down to sales (doesn’t everything?). Book sales, that is. When Les Misérables came out in 1862, Hugo was fretting about his readership and telegraphed the publishers. What did he write? Perhaps it was, “I was wondering how the book sales are going” (albeit in French, of course). Or, “Are my readers doing me proud and buying up all available copies of Les Misérables?” Neither actually—too wordy. Instead he graced his telegram with “?”. Yes, that’s right, “?”. His publishers promptly telegraphed back “!”. Their meaning was clear.

The second step on the noble eightfold path is: Avoid laziness. But, I hear you protest, Cessare humanum est (To idle is human). That may well be, but don’t try the editor’s patience. Here’s a common example: “Uncontrolled hypertensive patients.” What, in fact, does this mean? Does “uncontrolled” apply to hypertension or to the patients? Normally the editor will change this to “Patients with uncontrolled hypertension.” On a bad day, though, the editor may well be tempted to write “Psychotics.”

Step three on the noble eightfold path is: Avoid redundancy. Less is more. The minimalist’s maxim. Or to paraphrase the engineer and inventor Buckminster Fuller (he of the geodesic dome): “Do more with less.” Here’s an example. “An early effect was soon observed after 2-3 weeks.” I think we can agree that “early” and “soon” add nothing.

Avoid bias. Step four on the noble eightfold path. Naturally you wish to convince skeptics that your work is not only publishable, but worthy, important even. Egged on by a little voice in your head urging you to put everything into it, you may be tempted to use tendentious words and phrases to put an unjustified slant on what is written. Such as “The vast majority of” (All? Almost all? More than half?); “It is generally believed” (By whom?); “Interestingly” (Who says so?)… You get the idea.

The fifth step on the noble eightfold path is: Avoid imprecision. A common example will illustrate the problem: “The physical examination was abnormal.” An examination is not in itself abnormal or normal (or positive or negative). What is actually meant is: “The examination findings were abnormal.”

We are nearing enlightenment now, as we come to step six: Avoid abbreviations. Minimize them. They reduce readability. And if they (or acronyms) are necessary, expand them on first use, and don’t make up your own. Remember too that it’s pointless to define an abbreviation and then use it only two or three times in a 15-page article.

Step seven on the noble eightfold path is: Avoid inconsistency. This is selfexplanatory. Decide which spelling—British or American—is appropriate, and, if the journal doesn’t specify, choose one and stick with it. Use standard medical terms and don’t vary them in vain pursuit of some sort of literary “style.” Keep it simple, Stupid!

And here we are, finally, at enlightenment. At the eighth and last step on the noble eightfold path to a better manuscript. Avoid anarchy. Organize your manuscript. Format in the journal’s style. Do they want a structured abstract or not? What’s their policy on abbreviations? Do they use the Vancouver style for references? And if you feel yourself above such trivia, prepare for disappointment. And the return of your manuscript.

Have your manuscript checked by a native English speaker (preferably one with medical or scientific training). And if despite your best efforts the manuscript is rejected, don’t despair. You are in good company. Here’s a nonexhaustive list of scientists whose papers were initially turned down: Enrico Fermi (beta decay) 1938 Nobel Prize in Physics; Hans Krebs (Krebs cycle) 1953 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine; Pavel Cherenkov (Cherenkov radiation) 1958 Nobel Prize in Physics; Arthur Kornberg (DNA synthesis) 1959 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine; Rosalind Yalow (radioimmunoassay) 1977 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine; Sidney Altman (catalytic properties of RNA) 1989 Nobel Prize in Chemistry. They didn’t give up—they sent their work to other journals. In one survey, 85% of manuscripts rejected by Journal of Clinical Investigation were subsequently published elsewhere.

What then is the take-home message? It’s this: Write, rewrite, revise, all the while using what Ernest Hemingway considered the most valuable of writing aids—“a built-in, shock-proof shit detector.” Do you have one?

& transfer of copyright

Brigitte Oget-Chevret

Servier International, Suresnes, France

When you submit a manuscript , you will be asked to do two things that interest us here. One, give the publisher a list of your relationships with industry, thereby disclosing potential sources of conflict of interest relevant to the article submitted, and, two, once your article is accepted for publication, sign an agreement transferring copyright to the publisher.

Disclosure of potential conflict of interest

This is all about transparency and ethics. It has become common practice and, for years now, has been part of good publishing practices applied by all biomedical journals.

The ICMJE (International Committee of Medical Journal Editors) gives the following definition: “a conflict of interest exists when an author (or author’s institution), reviewer, or editor has financial or personal relationships that inappropriately influence (bias) his or her actions…”.1

All manuscripts are subject to disclosure of potential conflict of interest: editorials, letters, clinical cases, research or study manuscripts, review articles, articles in supplements, etc, and every signatory to the article has to provide to the publisher his/her own conflict of interest disclosure. Most journals will require it as part of the submission package.

What kind of information should be disclosed?

Financial ties are the most easily identifiable form of potential conflict of interest, and most journals will focus on this aspect of any relationships the authors may have with commercial entities. Clearly then all direct financial support from a commercial entity for the writing of the manuscript or for the study or for both will have to be disclosed in the manuscript. The reference period of time is the lifespan of the work/study reported. All indirect financial support, over the 3 years preceding submission, such as stock ownership, consultancies, paid travel expenses, board membership, honoraria, etc, as well as all financial support to the author’s institution should also be listed. In brief, authors are expected to disclose all relationships with commercial entities that may have a direct or indirect interest in the submitted work.

You may also want to disclose any personal relationships, particular ideology, or other information relevant to the article submitted that you think might be of interest to the Editor-in-Chief, peer reviewers, or, the readers, to help them understand the environment in which you wrote your article.

And if you are unsure whether or not you should declare something, err on the safe side and do so. You may think that something is not worth disclosing, but the Editor-in-Chief or peer reviewers or readers may think differently. Ultimately, the Editor-in-Chief will decide which of your disclosures to publish.

How should the disclosure be made?

Refer to the “authors” section of the journal’s Web site and follow the instructions. Each journal has its own policy when it comes to disclosing potential conflict of interest. Nevertheless, there are basically two options: either include a conflict of interest notification page in the manuscript itself, or use the standardized disclosure form which you can download from the ICMJE Web site,2 save on your computer and easily update for each new submission.

What happens if you forget to declare something?

It depends on when it happens, who realizes, and the degree of importance of the oversight. Before publication, there is always time to add the missing information. After publication, it may be a bit more complicated. A simple addendum in the next issue may suffice, but the publisher may decide to remove your article from its databases and even to go public. There are many well-publicized examples of undisclosed potential or real conflicts of interest revealed after publication of an article. Such situations can discredit you as an author, your work, the journal, and science itself.

Not only authors are concerned by conflict of interest disclosure. Editors-in-Chief and peer reviewers too are expected to make their own conflict of interest disclosures if, when receiving a manuscript or being asked to be a reviewer, they find themselves in a potential conflict of interest situation and therefore should not be involved in the assessment or review of the manuscript.

We all know that industry funding is very important in helping you advance medical knowledge and research. To maximize the impact of your work and publications, clear disclosure of potential conflicts of interest is vital. Transparency will prevent ambiguity and give increased validity and weight to your ideas and discoveries.

Copyright

With copyright, we are on legal ground. There are rules and regulations.

When it comes to copyright for literary and artistic works (writing an article for a biomedical journal falls into this category), the reference is the Berne Convention,3 dated 1886 and signed so far by 164 countries. This convention was designed to ensure international protection for creations for at least 50 years after the author’s death, and is automatic as soon as the creation exists in a physical medium.

The moral right and exploitation rights

The moral and exploitation rights are the two aspects of copyright. They offer recognition and economic reward to the author. When it comes to publishing, it is common practice for the author to transfer the exploitation rights (the right to represent, reproduce, distribute, translate, and create derivative works from the work) to the publisher, by signing a transfer of copyright agreement. Once you sign this document, the article no longer belongs to you but rather to the publisher, who becomes the “original publisher”.

Standard copyright agreements

Most print journals use copyright agreements that generally limit the author’s re-use of his/her work (in full or in part), without the publisher’s permission, to mainly personal or educational use, classroom use, posting of a Word-processed version of the article on the author’s personal or institutional Web site. But things are changing and more and more print journals use licenses (the author no longer transfers copyright to the publisher, but retains ownership of copyright and grants an exclusive license to the publisher to exploit the work and to represent him/her in consultation with third parties). Creative Commons Attribution Licenses, already used for years by many online and open-access journals, are more flexible and offer more possibilities to the author to re-use his/her work.

In this matter too, each publisher/journal has its own copyright policy,4 and you have to comply with it. Carefully read the document you sign to know what you can and cannot do.

Should you wish to use someone else’s published work, some on-line open-access journals like those published by BioMed Central5 and PLoS (Public Library of Science)6 provide, under license and certain conditions, free use of the articles. But in most cases you will have to seek written permission from the original publisher to re-use published material.

In all cases, keep in mind that you should always respect the integrity of the work, give proper credit to the author(s) and to the original publisher, otherwise you risk committing plagiarism or even self-plagiarism. The best way to avoid that is to cite the work fully (author(s), title, journal, full publication references, publisher).

img src=”https://www.phlebolymphology.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/02/14.jpg” alt=”” title=”” width=”682″ height=”175″ class=”aligncenter size-full wp-image-4135″ />

Last but not least, let’s get back to two elementary rules before submission: make sure that you have the authorization to submit from your co-authors and full authority to submit, and that your article is original and was not the object of a previous transfer of copyright.

References

1. www.icmje.org.Uniform Requirements for Manuscripts Submitted to Biomedical Journals: Ethical Considerations in the Conduct and Reporting of Research: Conflicts of Interest, www.icmje.org/ethical_4conflicts.html

2. Download this form from www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf

3. The Berne Convention is administered by the World Intellectual Property Organization. www.wipo.int, www.wipo.int/treaties/en/ip/berne/trtdocs_wo001.html

4. Check www.sherpa.ac.uk/romeo/ This Web site provides a summary of permissions that are normally given as part of each publisher’s copyright transfer agreement. Go to the “Browse” section and select “all publishers”.

5. www.biomedcentral.com/info/authors/license

6. www.plos.org/journals/, www.plos.org/oa/index.php, www.plos.org/oa/definition.php

Sébastien Cros

Servier International, Suresnes France

Finding relevant data is a key step before starting to write any scientific article. The Internet can be an incredibly rich source of information if you know how to refine your queries in search engines such as Google for general information and PubMed for scientific publications.

Google: tips and tricks

In France, nine out of ten people seeking information on the Internet use Google as a search engine. More than a minimalist search field and two main buttons, Google offers a large range of useful services that most users are unaware of.

For instance, Google can be used as a powerful calculator (enter the calculation in the search box and click on the search button). Google can also be used to convert different units of measurement, such as height, weight, and volume: see http://www.google.com/help/features.html.The language tools available on the Google homepage can help you to translate any text into more than 130 different languages. The “Translate a web page” function helps you to translate a full Web site into your own language, so that you can browse it without losing its initial layout. Go to http://www.google.com/language_tools?hl=en to read more about these features.

You can also use Google to search within a specific Web site you are interested in. Type “site:www.yourwebsite.com” in the search window to look for information within this Web site only. Or you can also use Google to search for terms used in a specific file type. For instance, if you are looking for a PowerPoint® presentation on venous disease, simply type in “filetype:ppt venous disease”. This trick works with the main file types, such as .doc, .txt, .xls, .jpg, and .ods.

Google News is a computer-generated news site that aggregates headlines from the main news sources worldwide. You can sort the news by date, relevance, or topic: visit Google News and search for “venous insufficiency” to find the most recent news about this subject. To receive regular automatic updates from Google News on this topic, you can create an e-mail alert by using the Google Alerts service, available at the following address: http://www.google.com/alerts

Use PubMed to find relevant publications

PubMed is a service of the US National Library of Medicine which includes more than 20 million scientific publications. You can use PubMed as a traditional search engine to find references of interest: complex queries can be made by using the Boolean operators AND, OR, NOT, brackets, and parentheses in order to refine your search and select relevant publications in the Medline database.

On top of that, you can register for a PubMed account and create e-mail alerts related to your favorite topics. Read more at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed