Assessment of treatment efficacy on venous symptoms: the example of MPFF at a dose of 500 mg

Neuilly-sur-Seine, France

INTRODUCTION

Leg symptoms are the most frequent reason why patients with chronic venous disease seek medical help. The patient hopes to get rid of them. This may explain the high consumption of venoactive drugs (VADs) in 10 countries (mostly European) in a recent survey: 17 million people per year are treated with VADs,* while 140 million among the adult population in these countries complain of leg symptoms.** The relationship between venous symptoms and venous signs is tenuous, as it is between venous symptoms and venous reflux. Therefore the medical literature concludes that these venous symptoms are nonspecific. This raises the question of the value of the available diagnostic tools and their specificity for venous symptoms. The present review considers tools currently used to assess efficacy in symptom management, some of which were used in efficacy studies of MPFF at a dose of 500 mg.

** Deduced from the percentage of symptomatic patients among adults (>18 years) in recent epidemiological trials in the 10 countries above

DEFINITION OF SYMPTOMS

A transatlantic interdisciplinary faculty of experts under the auspices of the American Venous Forum (AVF), the European Venous Forum (EVF), the International Union of Phlebology (IUP), and the International Union of Angiology (IUA) provided recommendations for venous clinical terminology in the Vein-TERM consensus document with the purpose of enhancing the use of a common scientific language in chronic venous disease (CVD) management and research.1 Venous symptoms are defined as: “aching or pain, burning, muscle cramps, swelling/throbbing sensation, heaviness,itching, restless legs, leg tiredness/fatigue. Although not pathognomonic, these may be suggestive of CVD if exacerbated with dependency on the day’s course, and heat, and relieved with leg rest and/or elevation, particularly in light of supportive clinical and/or laboratory evidence”.

PREVALENCE OF VENOUS SYMPTOMS

Venous symptoms are seldom reported in epidemiological studies. However, data in the general population from four countries show a high prevalence of venous symptoms ranging from 29% to 61%,2,3 with a clear predominance in women (Table 1), while data in populations seeking medical help4-6 show up to 75% prevalence of pain related to venous problems (Table 2).

Assessment of therapeutic effect on venous symptoms

Characterizing venous symptoms is the first goal when ensuring that symptoms are of venous origin. With CVD, treatment efficacy can basically be assessed in two ways: the patient’s quality of life assessment and the physician’s evaluation of clinical symptoms and signs.

Ascribing symptoms to chronic venous disease

The Phleboscore® by Blanchemaison7 is an 11-item selfadministered questionnaire which helps predict the risk of developing CVD. It includes questions about risk factors (gender, age, sedentary life, weight excess, number of pregnancies, working conditions, family history, sporting activities), as well as questions about the frequency of symptoms (heavy legs, sensation of swelling) and the circumstances in which symptoms worsen (heat, birth pill, long-haul travel). The score ranges from 0 to 31. A score >12 identifies patients at risk of CVD, while a score >23 pinpoints a need for venous exploration.

The VEINES-Sym by Lamping8 is a 10-item self-report questionnaire which includes questions on the frequency of 9 CVD-related symptoms (heavy legs, aching legs, swelling, night cramps, heat or burning sensation, restless legs, throbbing, itching, and tingling sensation), and the intensity of leg pain. The scores range from 0 to 10, with high values indicating better outcomes.

The more recent scoring system by Carpentier9 is a diagnostic tool administered to patients which aims to ascribe leg symptoms to CVD. This system “might also help predict the usefulness of treatment in patients with CVD seeking medical help for their symptoms”. It consists of a combination of 4 criteria: sensation of heavy or swollen legs, associated with itching, restless legs, or phlebalgia, worsened by a hot environment or improved by a cold environment, and not worsened by walking. Scores range from 0 to 4. With a threshold level of >3, there was a high specificity (0.95) and fair sensitivity (0.75) for CVD.

None of these 3 scales has been extensively studied, or validated except within a select research group during its development.

Patient-reported outcomes, and the use of generic and disease-specific quality of life scales10

The 13-item Aberdeen Varicose Veins Questionnaire addresses all features of varicose vein disease. Physical symptoms and social issues, including pain, ankle edema, ulcers, compression therapy use, and the effect of varicose veins on daily activities are examined, in addition to the effect of varicose veins from a cosmetic standpoint.

The 20-item ChronIc Venous disease quality of lIfe Questionnaire (CIVIQ) gives a global score, plus a score for each of the 4 areas in which quality of life is likely to be affected: physical, psychological, social, and pain. CIVIQ has been used in studies including a range of patients: Launois initially developed CIVIQ in a clinical trial of 934 patients and an epidemiologic survey of 26 681 patients, Neglén used it along with the CEAP classification in an 8-year study on venous outflow stenting, Lurie used it to compare two surgical procedures (stripping vs Closure®), and Jantet tested it in 3948 C0s to C4 patients. CIVIQ has been extensively used and is validated in 13 languages including Canadian English, English for Singapore, British English, American English, French Canadian, French for France, German for Austria, Greek, Italian, Polish, Portuguese for Portugal, and Spanish for Spain and for the USA.

The Charing Cross Venous Ulceration Questionnaire was developed to provide a valid quality of life measure for patients with venous ulcers and to assess the effects of the many treatments available for venous ulcers.

The VEINES instrument consists of 35 items in 2 categories to generate 2 summary scores. The VEINES quality of life questionnaire (VEINES-QOL) comprises 25 items that estimate the effect of disease on quality of life, and the VEINES symptom questionnaire (VEINESSym) has 10 items that measure symptoms. The focus of this instrument is on physical symptoms as opposed to psychological and social aspects. Coupled with the division of summary scores into symptoms and disease effect, this makes the VEINES instrument applicable to a range of clinical arenas. VEINES-QOL is validated in 4 languages: English, French (for Belgium and France), Italian, and French Canadian.

These four specific assessment tools were used in conjunction with the 36-item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36), which is the most widely used and validated generic quality of life instrument, whatever the medical field. The SF-36 has been developed over time with questions in the following two categories: physical health (assessed as the patient’s level of functioning) and mental health (assessed as an indication of well-being). These two groups have been broken down into 8 areas that include evaluation of physical and social functioning, role limitations due to physical or emotional problems, mental health, pain, vitality, and health perception. When complete, the survey generates a score ranging from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating better general health perception. The SF-36 has proven to be a good fit for generic quality of life assessment in the population with CVD.

Disease-specific reporting tools for physicians

The Clinical, Etiological, Anatomical, Pathophysiological (CEAP) classification has become a universal method of classification of venous disease.11 It can be used by the clinician in keeping office records of diagnostic information. Adoption of this single classification worldwide based on correct diagnosis has facilitated meaningful communication about the disease and served as a basis for a more scientific analysis of management alternatives.

The CEAP classification is descriptive, but cannot be used for venous severity scoring because many of its components are static and do not change in response to treatment. Therefore, a venous severity scoring system (VSSS) was proposed.12 It consists of 2 scores:

1) Venous Clinical Severity Score (VCSS). The VCSS includes 10 hallmarks of venous disease that are likely to show the greatest change in response to therapy and are scored on a scale of severity ranging from 0 to 3;

2) Venous Segmental Disease Score (VSDS). The VSDS uses the anatomic and pathophysiologic classifications in the CEAP system to generate a grade based on venous reflux or obstruction.

Of the various recommendations by the San Diego Consensus meeting regarding these tools, we can focus on the following:

• The CEAP classification is a descriptive instrument to categorize patients into different groups of severity of CVD;

• The VSSS, as presented by the AVF ad hoc committee on outcomes, is a useful complement to the CEAP classification, and should be used for research;

• Use of all CEAP components should be encouraged. However, use of only the clinical component (C) at the time of the initial evaluation is appropriate, and the E, A, and P components can be added as the diagnostic evaluation progresses.

Although reportedly easy to use, in the view of angiologists the VSSS is more likely to be of value in more severe cases of CVD.13 The descriptive CEAP and the VSSS, particularly the VCSS, are valid but imperfect instruments for evaluation of the early stages of CVD and treatment outcome. It seems that the time has come to revise the VCSS to allow proper reporting of common patient symptoms.

Nonspecific reporting tools for physicians

Analgesic consumption has proved a reliable indicator, if not reported solely by patients but also by physicians. Pain intensity can be reproducibly rated using a visual analog scale or numerical scale. Far more complex scales have been devised to rate the overall impact of pain. One of the most widely referenced is the McGill Pain Questionnaire. This questionnaire is duly validated, but is impractical in routine use and poorly adapted to CVD pain. The Brief Pain Inventory and the Multidimensional Pain Inventory explore the various dimensions of pain and its impact on activities of daily living, social repercussions, and psychological distress, thus making them very similar to quality of life questionnaires such as those specifically developed and validated for CVD.14

ASSESSMENT OF THERAPEUTIC EFFECT ON VENOUS SYMPTOMS: THE EXAMPLE OF MPFF at a dose of 500 mg

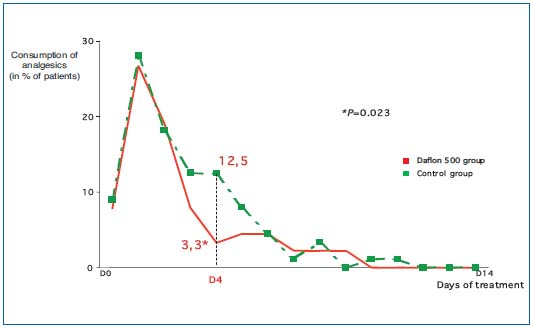

Using analgesic consumption In a multicenter study from the Czech Republic, Veverkova and co-workers compared the outcome of varicose vein surgery in two groups of patients. The treatment group (n= 92) received MPFF at a dose of 500 mg, 2 tablets/day, starting two weeks before surgery and continuing for up to 14 days after the procedure. The control group (n=89) did not receive MPFF at a dose of 500 mg in the pre- and postoperative periods. It was shown that the drug significantly reduced analgesic consumption within 2 weeks after surgery.15 (Figure 1)

Figure 1. Evaluation of analgesic consumption to assess the efficacy

of MPFF at a dose of 500 mg treatment of postsurgical pain.

Using the 10-cm visual analog scale

In the large, prospective, multicenter RELIEF trial, 3132 patients assigned CEAP classes C0s to C4 were assessed for pain. Patients with or without venous reflux showed significant reduction in pain as assessed by visual analog scale scores (GIS) after 2, 4, and 6 months of treatment (P=0.0001).16

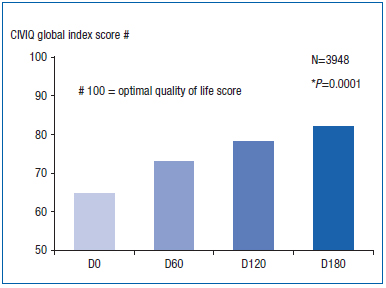

Using the CIVIQ

Improvements in the clinical signs and symptoms of CVD with 2 tablets of MPFF at a dose of 500 mg twice daily were associated with significant improvements in CIVIQ (health-related quality of life) scores in the RELIEF trial. The C0s to C4 patients showed significant improvement in CIVIQ global index scores (GIS) after 2, 4, and 6 months of treatment (P=0.0001). GIS increased throughout the study period with the largest improvement occurring during the first 2 months of treatment.16 (Figure 2)

Figure 2. Use of CIVIQ to assess improvement in the quality of life

of C0s to C4 patients with MPFF at a dose of 500 mg treatment.

Using both the 10-cm visual analog scale and the CIVIQ

In a double-blind study vs placebo, 592 C3 to C4A patients with superficial (mean 34%), deep, or perforator reflux (mean 66%) and severe pain over 4 cm on the visual analog scale were analyzed. Patients in the treatment group received MPFF at a dose of 500 mg, 2 tablets a day, while those in the placebo group received 2 tablets of placebo/day. A pain decrease of at least –3 cm on the visual analog scale and a significant quality of life improvement of at least 20 on the CIVIQ scale were the end points. The results were significantly in favor of the MPFF at a dose of 500 mg group (RR=1.67) (unpublished data).

Using the 5-point numerical scale

MPFF at a dose of 500 mg, two tablets daily, maintained its efficacy in the long-term treatment of patients with symptoms of CVD in a nonblinded, multicenter trial of 12 months’ duration. In 170 evaluable patients, a significant reduction from baseline values in physician-assessed clinical symptoms (using a numerical scale of 0 to 5) was demonstrated at each 2-month evaluation (P<0.001). The rapid reductions observed during the first 2 months of treatment represented approximately 50% of the total improvement ultimately observed after 1 year of treatment. Continuing improvements in all parameters, albeit less rapid, were reported at each timepoint from month 2 to month 12.17

Percentage of patients without symptoms after therapy

A simple way to assess the effect of therapy on symptoms uses statistical analysis of the percentage of patients who no longer present with the symptoms.

The efficacy of MPFF at a dose of 500 mg in decreasing symptoms associated with venous ulcers was evaluated in a metaanalysis of 5 randomized trials including 459 patients. Two tablets of MPFF at a dose of 500 mg daily plus standard venous ulcer management was compared with standard venous ulcer management (compression therapy plus local treatment). Patients were included in the trials if they had a venous leg ulcer for a duration of at least 3 months. Significant symptom reduction in favor of the MPFF at a dose of 500 mg group was seen after 4 and 6 months of treatment (P<0.001).18

INDICATIONS OF MPFF at a dose of 500 mg AND RECOMMENDATIONS IN GUIDELINES

MPFF at a dose of 500 mg is a well-established treatment option and is strongly recommended in the recent guidelines for patients with CVD.19,20 MPFF at a dose of 500 mg is indicated as a first-line treatment of edema and the symptoms of CVD in patients at any stage of the disease. At more advanced disease stages, MPFF at a dose of 500 mg may be used in conjunction with sclerotherapy, surgery, and/or compression therapy, or as an alternative treatment when surgery is not indicated or is unfeasible.21 The healing of venous ulcers is accelerated by the addition of MPFF at a dose of 500 mg to standard venous ulcer management (compression therapy and local treatment).22

CONCLUSION

There is no universal consensus as to which outcome tool should be used to assess CVD-related symptoms. Quality of life questionnaires are valuable indicators, but some are still cumbersome and need to be simplified. Venous scoring systems like the VCSS should be more adapted to the early stages of CVD. The few existing scoring systems that can ascribe symptoms to venous disease are still poorly used. The tools used to quantify and qualify venous symptoms, either through patients’ self-report questionnaires or by physician reporting, have been widely validated. These tools have also been used to assess the efficacy of treatments of venous symptoms, as in the case of MPFF at a dose of 500 mg.

References

2. Carpentier P. Prevalence, risk factors and clinical significance of venous symptoms. Medicographia. 2006;28:168- 170.

3. Langer RD, Ho E, Deneberg JO, et al. Relationships between symptoms and venous disease. Arch Int Med. 2005;165:1420-1424.

4. Scuderi A, Raskin B, Al Assal F, et al. The incidence of venous disease in Brazil based on the CEAP classification. An epidemiological study. Int Angiol. 2002;21:316-321.

5. Carpentier PH., Cornu-Thénard A, Uhl JF, Partsch HJF, Antignani PL. Appraisal of the information content of the C classes of CEAP clinical classification of chronic venous disorders. A multicenter series of 872 patients. J Vasc Surg. 2003;37:827-833.

6. Jawien A, Grzela T, Ochwat A. Prevalence of chronic venous insufficiency in men and women in Poland: multicentre cross-sectional study in 40095 patients. Phlebology. 2003;18:110-122.

7. Blanchemaison P. Evaluation pratique du risque veineux: le Phléboscore®. Act Vasc Int. 2000;81:12-16.

8. Lamping DL, Schroter S, Kurz X, Kahn SR, Abenhaim L. Evaluation of outcomes in chronic venous disorders of the leg: Development of a scientifically rigorous, patient-reported measure of symptoms and quality of life. J Vasc Surg. 2003;37:410-419.

9. Carpentier PH, Poulain C, Fabry R, et al. Ascribing leg symptoms to chronic venous disorders: the construction of a diagnostic score. J Vasc Surg. 2007;46:991-996.

10. Vasquez MA. Venous Clinical Severity Score and Quality-of-Life Assessment Tools: Application to Vein Practice. J Vasc Surg. In press.

11. Eklöf B, Rutherford RB, Bergan JJ, et al; American Venous Forum International Ad Hoc Committee for Revision of the CEAP Classification. Revision of the CEAP classification for chronic venous disorders: consensus statement. J Vasc Surg. 2004;40:1248- 1252.

12. Rutherford RB, Padberg FT Jr, Comerota AJ, Kistner RL, Meissner MH, Moneta GL; American Venous Forum’s Ad Hoc Committee on Venous Outcomes Assessment. Venous severity scoring: An adjunct to venous outcome assessment. J Vasc Surg. 2000;31:1307-1312.

13. Perrin M, Dedieu F, Jessent V, Blanc MP. Evaluation of the new severity scoring system in chronic venous disease of the lower limbs: an observational study conducted by French angiologists. Phlebolymphology. 2006;13:6-16.

14. Allaert FA. Pain scales in venous disease: methodological reflections. Medicographia. 2006;28:137-140.

15. Veverkova L, Jedlika V, Wechsler J, et al. Analysis of the various procedures used in great saphenous vein surgery in the Czech Republic and benefit of MPFF at a dose of 500 mg on postoperative symptoms. Phlebolymphology. 2006;13:195-201.

16. Jantet G; RELIEF Study Group. Chronic Venous Insufficiency: Worldwide Results of the RELIEF Study. Angiology. 2002;53:245-256. 17. Guillot B, Guilhou JJ, de Champvallins M, et al. A long term treatment with a venotropic drug: results on efficacy and safety of MPFF at a dose of 500 mg in chronic venous insufficiency. Int Angiol. 1989;8:s67-s71.

18. Coleridge-Smith P, Lok C, Ramelet AA. Bénéfice thérapeutique de la FFPM dans le traitement des symptômes associés aux ulcères veineux de jambe: une méta-analyse. J Mal Vasc. 2007;32:s38

19. Ramelet A-A and the experts of the international consensus symposium of Siena 2005. Veno-active drugs in the management of chronic venous disease. An international consensus statement: current medical position, prospective views and final resolution. Clinical Hemorheol Microcirc. 2005;33:309-319.

20. Nicolaides AN, Allegra C, Bergan J, et al. Management of chronic venous disorders of the lower limbs. Guidelines according to scientific evidence. Int Angiol. 2008;27:1-59.

21. Lyseng-Williamson A, Perry CM. Micronised purified flavonoid fraction. A review of its use in chronic venous insufficiency, venous ulcers and haemorrhoids. Drugs. 2003;63:71-100.

22. Coleridge-Smith P , Lok C, Ramelet AA. Venous leg ulcer: a meta-analysis of adjunctive therapy with micronized purified flavonoid fraction. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2005;30:198-208.