Chronic venous disease in general practice in the Slovak Republic: the TRIANGLE Survey

Viera STVRTINOVA

Second Department of Internal Medicine,

Medical Faculty of Comenius University,

Bratislava, Slovak Republic

RATIONALE OF THE TRIANGLE SURVEY

IN THE SLOVAK REPUBLIC

The TRIple Assessment in chronic venous disease linkiNg siGns, symptoms and quaLity of lifE (TRIANGLE) Survey is a screening program initiated by Servier. TRIANGLE is an international observational research program designed to provide information on the prevalence of chronic venous disease (CVD) and to help achieve better understanding of the triangular relationship between symptoms, signs, and the quality of life in patients suffering from CVD.

The Slovakian TRIANGLE program, which is reported in this paper, was professionally endorsed by the Slovakian Medical Association for Angiology. The program was focused mostly on the prevalence of symptoms and signs of CVD in Slovakia, with some data reported on the quality of life. No validated quality of life questionnaire was used, but a simple six-item questionnaire was to be filled in by patients. Part of these recent surveys used the basic Clinical, Etiologic, Anatomic, Pathophysiologic (CEAP) classification,1 in which the single highest descriptor is used for clinical class. The aim of the program was not only to diagnose patients with CVD in a primary care setting, but also to broaden knowledge of the incidence on well-being of particular clinical stages of CVD as well as of associated symptoms.

INTRODUCTION

CVD of the lower limbs is often characterized by symptoms and signs as a result of structural or functional abnormalities of the veins.2 Symptoms include aching, heaviness, leg tiredness, cramps, itching, burning sensations, swelling, and restless legs syndrome. Signs include telangiectasias, reticular and varicose veins, edema, and skin changes such as pigmentation, lipodermatosclerosis, dermatitis, and ultimately venous leg ulceration.2

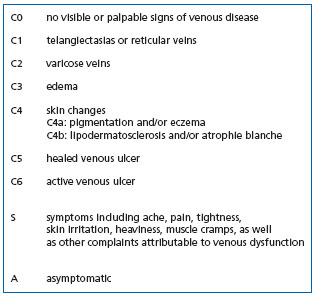

CVD signs are described in the CEAP classification1,3 which comprises four components, ie, the clinical (C), etiologic (E), anatomic (A), and pathophysiologic (P) aspects of such signs. Basic CEAP should include all four components, but the majority of general practitioners do not have a duplex scan that provides data on E, A, and P. The highest descriptor is used for clinical class in the basic CEAP (Table I).

Table I: Clinical classification of chronic venous disease according

to the revised CEAP1

Symptoms are not specific to CVD and to be attributed to CVD should meet at least two of the following criteria:4 exacerbated after prolonged standing, but diminished after rest, or improve or disappear on walking, exacerbated at the end of the day, but disappear in the morning, after night rest, exacerbated by warmth (summertime, hot baths, floor-based heating systems, hot waxing to remove body hair), but are less intense in winter and at low temperatures, and for women, exacerbated before menstruation or occur with hormonal therapy, but disappear with discontinuation of such treatment, or after the menstruation.

The aim of the Slovakian TRIANGLE survey was to provide updated figures on the prevalence of symptoms and signs of CVD, using clear and globally accepted clinical definitions for venous disease, based on the CEAP classification.1

MATERIAL AND METHODS

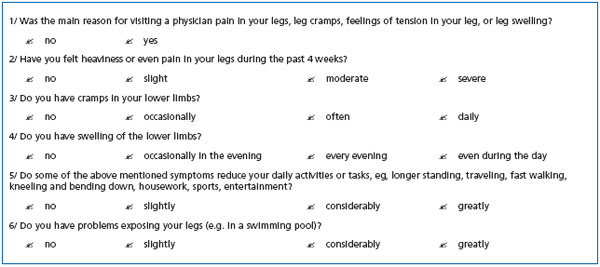

Investigators could include consecutive patients within a period of 20 continuous days. These were adults (> 18 years) consulting for general health care, whether for cardiology, diabetology, or infectious diseases. To be enrolled in the survey, patients had to present with subjective symptoms and/or objective signs of CVD. Investigators had to examine patients’ lower limbs and assign them a class according to the C of the CEAP classification (Table I). Patients willing to cooperate were requested to fill out a questionnaire consisting of six simple questions dealing with the incidence of subjective symptoms on their daily lives (Table II).

Table II: Questionnaire to be filled in by patients

RESULTS

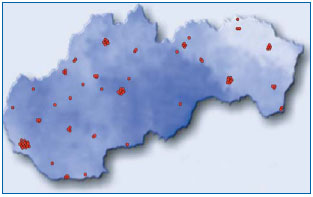

A total of 99 GPs from all parts of Slovakia were involved in the TRIANGLE study (Figure 1). They enrolled 3134 patients who met the inclusion criteria defined above.

Signs of CVD

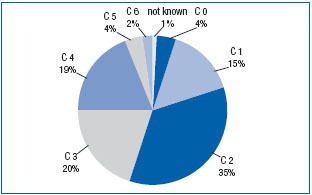

Figure 2 shows the results of medical examinations of the lower limbs of the 3134 examined individuals using the CEAP classification. The largest proportion of patients— 35%—was assigned class 2 (trunk varicose veins) of the CEAP, 20% had edema (C3), and 19% had skin changes (C4). Telangiectasias and reticular veins were present in 15% of examined patients. A quite high proportion of patients had active (2%) or healed (4%) venous leg ulcers.

Figure 2. Distribution of patients according to the CEAP classification

Symptoms of CVD

Four per cent (4%) of patients suffered from subjective symptoms of CVD (heaviness, aching, edema, cramps) without associated objective signs of the disease. Such patients can be classified as C0s according to the C of the CEAP. A duplex scan could have told us whether they had reflux or not.

Symptoms like leg heaviness and pain in the lower limbs were present in 77% of patients, 13% of whom

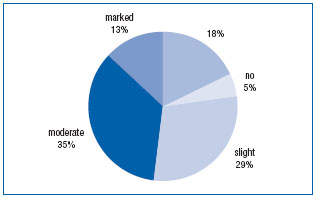

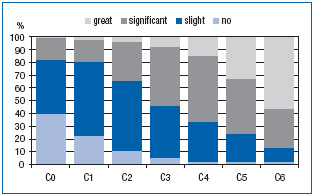

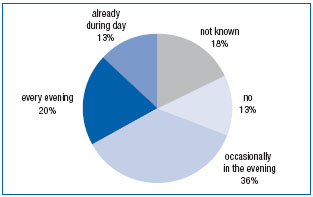

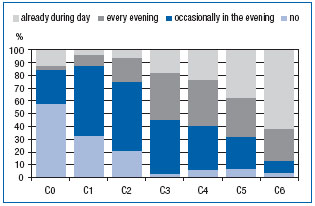

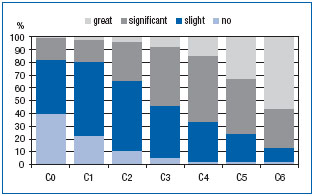

complained of severe pain (Figure 3). With progression of the clinical stages of the disease, the percentage of patients with moderate to severe pain increased (Figure 4), since 42% patients with healed varicose ulcer (C 5) and 70% of those suffering from active varicose ulcer (C 6) had severe pain. Intermittent edema of the lower limbs was reported by 36% of patients (Figure 5). In 20% of patients, the edema appeared every evening, and 13% of patients noticed the edema occurring already during the daytime. With disease progression, the percentage of those with edema every day increased (Figure 6). Similarly, the frequency of cramps increased with clinical stage (not shown).

Figure 3. Severity of pain and/or leg heaviness in patients with CVD

Figure 4. Severity of pain and/or leg heaviness according to CEAP class

Figure 5. Frequency of edema in patients with CVD

Figure 6. Frequency of edema according to CEAP class

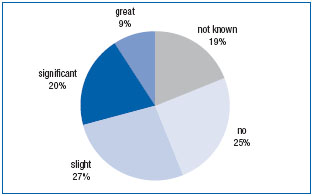

Quality of life

Data from the self-administered questionnaires (see Table II) indicated that the quality of life of patients suffering from venous disease was decreased compared with that of the healthy population (Figure 7). More than half (56%) of patients were embarrassed to show their legs because of visible signs of CVD. As a consequence, these patients avoided going to the swimming pool and, for women, wearing skirts. A third had very serious or substantial social problems. The number of individuals who were prevented from doing certain daily activities or tasks increased with disease severity (Figure 8).

Figure 7. Distribution of patients according to the cosmetic embarrassment they feel due to leg problems

Figure 8. Reduction of daily activities in patients with CVD

DISCUSSION

A recent survey in the USA5 reported visible signs like telangiectasias, varicose veins, and trophic changes in 67% of men and 89% of women with CVD. Telangiectasias and reticular veins are the most widespread signs of CVD in the countries of Europe,4 accounting for 50% in men and 65% in women.6 Little epidemiologic research has been conducted in Eastern Europe.6,7 In a cross-sectional survey among 40 095 individuals of the adult population in Poland, a prevalence of CVD signs similar to that observed in Western countries was reported. A high prevalence of varicose veins was found in the Slovak Republic in a previous survey among 696 female employees in a department store: telangiectasias in 30.7%, reticular varicose veins in 15.4%, and trunk varicose veins in 14.4%, which means 60.5% of women with visible varices.7 In the present TRIANGLE survey, the proportion of patients with varicose veins is slightly higher (35%) and with telangiectasias and reticular veins less (15%) than in our previous trial7 and in the medical literature.4-6 This may be the result of a discrepancy in the evaluation of “visible” signs by GPs (as in the present survey) compared with specialists, who investigate patients in most epidemiological publications. Active and healed ulcers were more prevalent in the TRIANGLE survey ( respectively, 2% and 4%) than in other reports, in which its prevalence does not exceed 0.5% to 1%.

We found a correlation between the severity of CVD according to the CEAP C classes and the prevalence of venous symptoms, in agreement with previous trials.4,5,8,9 In Edinburgh, Ruckley et al8 found a significant correlation between the severity grades of CVD (assessed according to the Widmer classification) and the prevalence of heaviness/tension, feeling of swelling, aching, and itching. Criqui et al in San Diego5 found an increased prevalence of symptoms with increasing severity of signs, in agreement with the findings of Kahn9 and Carpentier.4

In spite of the high incidence of the disease-related signs as mentioned above and of their considerable social and economic burden for society, there is still only a partial understanding of the pathogenesis of such chronic disorders. This probably explains the insufficient management of patients with CVD. Not uncommonly, unsatisfactory treatment outcomes in CVD are the result of negligence of health care providers themselves, not to mention insufficient clinical and instrumental examination of patients, as well as improper therapeutic methods.10 As Professor John Bergan points out,11 it is an unfortunate fact that research interest and funding attracted by CVD has been in inverse proportion to its prevalence and socioeconomic burden and this state of affairs is unwarranted, not simply for humanitarian reasons, but also in terms of fundamental research. Furthermore, varicose veins of the lower limbs are often considered a merely cosmetic defect. However, the “trivial” varicose veins of the lower limbs usually presage the development of a full spectrum of pathologic conditions ranging from mild signs of CVD to ulcer of the lower limbs, with possible fatal pulmonary embolism. Early treatments including lifestyle changes, mechanical devices, and oral drugs may prevent or slow the development and recurrence of troublesome outward manifestations

CONCLUSION

The TRIANGLE program has confirmed the high prevalence in Slovakia of CVD, which can cause considerable subjective symptoms and frequent social problems for sufferers. The survey findings show that CVD treatment must be both timely and complete.

REFERENCES

2. Nicolaides AN, Allegra C, Bergan J, et al. Management of Chronic Venous Disorders of the Lower Limbs. Guidelines According to Scientific Evidence. Int Angiol. 2008;27:1-59.

3. Porter JM, Moneta GL. International Consensus Committee on chronic venous disease. Reporting standards in venous disease: an update. J Vasc Surg. 1995;21:635-645.

4. Carpentier P. Prevalence, risk factors and clinical significance of venous symptoms. Medicographia. 2006;28:168-170.

5. Criqui MH, Denenberg JO, Langer RD, et al. Epidemiology of chronic peripheral venous disease. In: Bergan JJ, ed. The Vein Book.1st ed. San Diego, Calif: Elsevier; 2007:27-38.

6. Jawien A, Grzela T, Ochwat A. Prevalence of chronic venous insufficiency in men and women in Poland: multicenter crosssectional study in 40 095 patients. Phlebology. 2003;18:110-122.

7. Stvrtinová V, Kolesár J, Wimmer G. Prevalence of varicose veins of the lower limbs in the women working at a department store. Int Angiol. 1991;10:2-5.

8. Ruckley CV, Evans CJ, Allan PL, et al. Chronic venous insufficiency: Clinical and duplex correlations. The Edinburgh Vein Study of venous disorders in the general population. J Vasc Surg. 2002;36:520-525.

9. Kahn SR, M’lan CE, Lamping DL, et al. Relationship between clinical classification of chronic venous disease and patientreported quality of life: Results from an international cohort study. J Vasc Surg. 2004;39:823-828.

10. Ramelet AA. Drug therapy. In: Ramelet AA, Monti M, eds. Phlebology – The Guide.4th ed. Paris, France: Masson; 1999:303-318.

11. Bergan JJ, Schmid-Schönbein G, Coleridge-Smith P, et al. Chronic venous disease. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:488-498.