Premenstrual symptoms in lower limbs and Duplex scan investigations

SUNY – Stony Brook School of Medicine

ABSTRACT

Objectives: Approximately 40% of menstruating women experience luteal phase symptoms that are bothersome. Although the distinguishing characteristic is irritability, symptoms typically are a mix of cognitive and physical disturbances. Leg swelling and discomfort are one such physical symptom. The goal of the study is to define the clinical entity of a late luteal phase vasodilation syndrome in symptomatic patients.

Methods: Duplex venous scans were performed in the standing position on 12 premenopausal women (age range 19-46 years) who described premenstrual symptoms of bilateral leg swelling, pressure, or pain. One scan was performed during the follicular phase (days 3-6) and one during the luteal phase (days 20-24). Great saphenous vein (GSV) diameter and reflux (with calf augmentation) were measured mid-thigh.

Results: Seventeen limbs in 12 patients were studied. An increase in GSV diameter and reflux was appreciated in 100% (12/12) of symptomatic patients and (17/17) limbs when scanned in the follicular and luteal phases of the menstrual cycle. Follicular phase GSV diameters ranged from 2.0 to 7.2 mm. Luteal phase GSV diameters ranged from 2.5 to 8.0 mm. Follicular phase reflux ranged from 0 to 2.5 seconds. Luteal phase reflux ranged from 1.5 to 5.0 seconds.

Conclusions: Lower extremity swelling, pain, and discomfort are common complaints of menstruating women in the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle. Symptoms seem to be related to vasodilation and reflux—perhaps mediated by the effects of progesterone, which serves as a smooth muscle relaxant and the dominant hormone of the luteal phase. Further studies can employ the use of a control group, measurement of serum progesterone levels ,and evaluation of the use of graduated compression therapy as a treatment option.

INTRODUCTION

The clinical management of unpleasant premenstrual symptoms is difficult. Although recognized in the medical literature for over a century, it is only over the past 20 years that there has been a consensus regarding the diagnosis of premenstrual syndrome (PMS). Early literature described this condition as “premenstrual tension,”1 referring to a constellation of symptoms occurring during the week prior to menstruation and ending with the onset of menstrual flow. Strict diagnostic criteria have been used to study pathophysiology and therapy.2 In general, approximately 40% of menstruating women experience bothersome luteal phase symptoms. For 25%, these symptoms are annoying but do not impair daily functioning. In about 15% symptoms are severe, with 3% of these women experiencing significant impairment in daily functioning.3,4

Characteristic symptoms include a mixture of cognitive and physical disturbances. The hallmark feature is irritability separate and distinct from depression or anxiety disorders.5 Physical disturbances include migraine headaches, mastalgia, gastrointestinal disturbances, and leg pain among others. Leg pain may be described as “dull” and “aching.” These are typical of the symptoms associated with patients with chronic venous insufficiency and varicose veins. This study is designed to define the clinical entity of a late luteal phase vasodilation syndrome in symptomatic patients. Comparison is made of GSV diameter and reflux in both the follicular as well as the luteal phases of the menstrual cycle.

METHODS

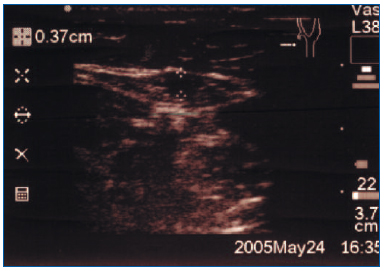

Duplex venous scans (Sonosite 180 plus; Bothell, WA) were performed in the standing position on 12 premenopausal women (age range 19-46 years) who described premenstrual symptoms of bilateral or unilateral leg swelling, pressure, or pain. These symptoms were present premenstrually and resolved with the onset of menstrual flow. One scan was performed during the follicular phase (days 3-6) and one during the luteal phase (days 20-24) of the menstrual cycle. GSV diameter and reflux were measured mid-thigh. B-mode was used to measure GSV diameter (Figure 1).

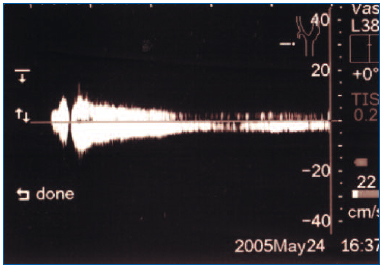

Reflux was appreciated with calf augmentation (Figure 2). Doppler mode was used to assess reflux. Temperature of the examination room was controlled at 22 degrees centigrade.

Figure 1. Transverse measurement of great saphenous vein in saphenous sheath.

Figure 2. Assessment of reflux in great saphenous vein.

RESULTS

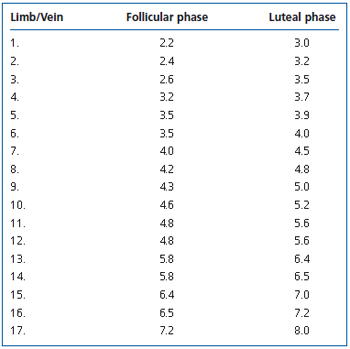

Seventeen limbs in 12 patients were examined. An increase in GSV diameter and reflux was appreciated in 100% (12/12) of symptomatic patients and (17/17) limbs when scanned in the standing position during the follicular and luteal phases of the menstrual cycle. Follicular phase GSV diameters ranged from 2.0 to 7.2 mm (mean 4.46 mm). Luteal phase GSV diameters ranged from 2.5 to 8.0 mm (mean 5.11 mm). This is equivalent to a 15% increase in GSV diameter (Table I).

Table I. Great saphenous vein diameter in millimeters.

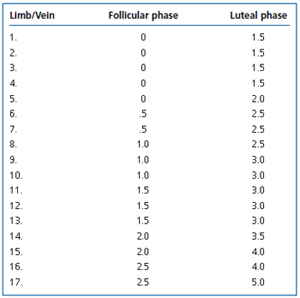

Follicular phase reflux ranged from 0 to 2.5 seconds (mean 1.03 seconds). Luteal phase reflux ranged from 1.5 to 5.0 seconds (mean 2.76 seconds). This is equivalent to a 168% increase in GSV reflux (Table II).

Table II. Great saphenous vein reflux in seconds.

CONCLUSIONS

Lower extremity swelling, pain, and discomfort are common complaints of menstruating women in the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle. Symptoms seem to be related to vasodilation and reflux—perhaps mediated by the effects of progesterone, which serves as a smooth muscle relaxant and is the dominant hormone of the luteal phase. Menses, along with a resolution of symptoms, coincides with a decrease in progesterone levels, a phenomenon known as “progesterone withdrawal.”

This preliminary study can serve as a template for further investigation into the venous changes associated with hormonal changes unique to the premenopausal female patient. This condition may aptly be termed “premenstrual vasodilation syndrome,” consisting of symptoms of lower extremity swelling, pressure, and pain characteristic of the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle. A control group consisting of asymptomatic patients would be helpful. Measurement of serum progesterone levels may also be of interest. Additionally, assessing the qualitative and quantitative therapeutic effects of graduated compression and hormonal therapy may be of value. Well-designed, placebo-controlled clinical trials have been conducted for some pharmacologic agents. However, use of these agents may help some aspects of PMS while aggravating others.6 For patients in whom these more conservative therapies fail, exploration of endoluminal therapy such as ultrasound-guided sclerotherapy, radiofrequency, and laser would be indicated.

REFERENCES

2. Endicott J. History, evolution and diagnosis of premenstrual dysphoric disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000;61(suppl 12):5-8.

3. Johnson SR. The epidemiology and social impact of premenstrual symptoms. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1987;30:367-376.

4. Sternfeld B, Swindle R, Chawla A, et al. Severity of premenstrual symptoms in a health maintenance organization population. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;99:1014-1024.

5. Endicott J, Amsterdam J, Eriksson E, et al. Is premenstrual disorder a distinct clinical entity? J Womens Health Geno Based Med. 1999;8:663-679.

6. Barnhart KT, Freeman EW, Sondheimer SJ. A clinician’s guide to the premenstrual syndrome. Med Clin North Am. 1995;79:1457- 1472.