Is compression necessary after endovenous thermal ablation of varicose veins? Clarifying a (com)pressing matter

MRCS, AFHEA;

Alun H. DAVIES, MA, DM, DSc,

FRCS, FHEA, FEBVS, FLSW,

FACPh

Surgery and Cancer, Charing Cross

Hospital, Imperial College London,

London, United Kingdom

Abstract

Chronic venous disease (CVD) represents a significant impact on patients’ lives with negative financial, social, and health-related quality of life consequences. The gold standard for treatment of varicose veins and CVD is now considered to be endovenous thermal ablation (EVTA). Although compression is widely prescribed for patients post EVTA, there is widespread disagreement on the optimal compression regimen and if compression is even required postoperatively. This review reexamines the literature surrounding this important clinical question, presenting current clinical opinion and practices and guideline recommendations, and discusses the evidence for and against the use of compression postoperatively. It further considers the differences between the benefits of compression observed in endovenous laser ablation and radiofrequency ablation. Overall, the data still indicate the lack of knowledge regarding the efficacy of post-EVTA compression. Although using compression for a longer duration post EVTA appears to have some impact on early postoperative pain, these conclusions are potentially confounded by a multitude of variables including analgesia regimen, adherence to compression therapies, and energy modality. The literature suggests that extending compression beyond 7 days is unlikely to confer any additional benefits, but due to these confounding variables, further clarification is required to determine if compression type and duration should be personalized to target specific groups of patients, or if any compression post EVTA is required at all.

Introduction

The term chronic venous disease (CVD) covers a spectrum of clinical presentations, which increase in severity from telangiectasia to varicose veins, edema, skin changes, and eventually, venous ulceration.1 These presentations significantly impact patients’ lives, with negative health-related quality of life (HRQOL) changes related to chronic pain, decreased mobility, social isolation, and other psychosocial issues.2,3 CVD is a common condition, with varicose veins affecting up to 40% of the population and venous ulcers prevalence being up to 4% in patients above the age of 65.4

Historically, the management of varicose veins involved surgical ligation and stripping of saphenous veins. However, since the beginning of the 21st century, there has been a rapid evolution of endovenous thermal ablation (EVTA) technologies, with endovenous laser ablation (EVLA) and radiofrequency ablation (RFA) shown to be as clinically effective as these surgical techniques. Endovenous interventions for this disease have been found to be cost-effective in multiple trials5,6 and even more so when performed in an outpatient setting.7 These techniques are now considered “gold-standard” and are endorsed by national and international guidance.8,9

What is perhaps less clear is the prescription of compression after EVTA (Figure 1). Although compression after EVTA is widely thought to be beneficial and is regularly provided in clinical practice and randomized controlled trials (RCTs), there exists significant debate over its impact on clinical and patient-reported outcomes. Even if compression is assumed to be beneficial after EVTA treatment, there is still widespread disagreement regarding the type (bandages versus stockings), level, and duration of the compression regimen.

Figure 1. Compression stockings used after endovenous thermal ablation. Photo provided courtesy of Alun H. Davies.

Clarifying this matter is of utmost importance for a few reasons. Firstly, compression is often poorly tolerated by patients–a survey reported that only 29.1% of patients consider compression therapy to be “comfortable.”10 Extended durations of compression may also contribute to skin irritation, leading to negative impacts on patients’ HRQOL, contrary to treatment intentions. Secondly, in view of this discomfort and potential adverse effects, adherence to compression therapy is a known challenge, with adherence rates estimated to be as low as 30% in trials.11,12 Finally, from a financial point of view, regular use of compression post EVTA may represent an unnecessary cost should this not provide any benefits to patients. This is an area of potential cost savings for patients and the health care service, estimated at up to £182 per patient per annum.13

Current practices

In 2016, a survey was sent out to consultant members of the Vascular Society of Great Britain and Ireland, with questions on their prescribing patterns of compression following treatment of varicose veins.14 Although all respondents prescribed compression after EVTA, the duration ranged from 2 days to 6 weeks and 4 different combinations of stockings, bandages, and paddings were used in these prescriptions. Only 28% of vascular units used the same method, and 10% used the same duration of compression.

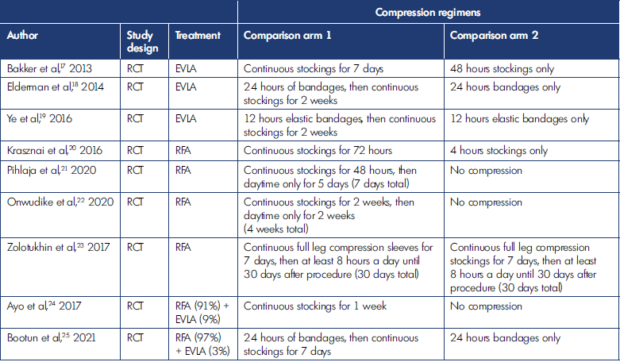

This discordance in practice was noted in the literature as well. Systematic reviews from the same year observed compression strategies used in randomized clinical trials that included endovenous ablation as a trial arm, showing compression to be prescribed for anywhere between 2 days to 6 weeks.15,16 Most trials used stockings and bandages in combination or bandages alone for an initial duration of compression, after which most patients were switched to isolated stockings for the remainder of the prescription. This inconsistency in compression regimens can also be seen in the studies identified in this review (summarized in Table I17-25).

What do the current guidelines say?

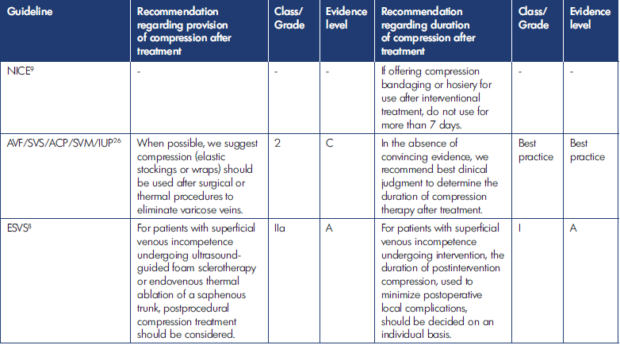

As mentioned above, international guidelines are quite unanimous regarding their recommendations for supporting the use of EVTA options in the treatment of varicose veins and CVD, with such technologies now the gold-standard treatment for varicose veins. These guidelines, however, are less unified when it comes to recommending compression after EVTA (examples from the United States [US], the United Kingdom, and Europe are summarized in Table II).

In the context of the authors’ national guidelines, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends the use of compression (bandages or hosiery) for no more than 7 days after intervention.9 However, recognizing the uncertainty of evidence surrounding compression compared with no compression after treatment, the NICE Guideline Development Group advocated further research into this postintervention treatment, with specific questions regarding its clinical- and cost-effectiveness. This guideline, however, was formulated in 2013 and the new evidence published since then might change recommendations in its future iterations.

Table I. Different compression regimens used in the studies included in this review. EVLA, endovenous laser ablation; RCT, randomized controlled trial; RFA, radiofrequency ablation.

Table II. Current guidelines and recommendations for post-endovenous-thermal-ablation (EVTA) compression. ACP, American College of Phlebology; AVF, American Venous Forum; ESVS, European Society for Vascular Surgery; IUP, International Union of Phlebology; NICE, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; SVM, Society for Vascular Medicine; SVS, Society for Vascular Surgery.

More recent guidelines from societies from the US26 and the European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS)8 do provide recommendations regarding providing compression after EVTA. These recommendations, however, are of weak to moderate strength. The recommendation from the US societies, for example, suggests provision of compression after EVTA, but this recommendation is graded as 2C (“weak recommendation, low-quality or very-low-quality evidence”). That from the ESVS recommends that clinicians “consider” providing postprocedural compression. This recommendation, however, has been downgraded to class IIa in the latest edition of the guidelines, suggesting conflicting evidence but in favor of usefulness or efficacy. These two guidelines also were not able to provide firm durations for compression use, suggesting that it be left to “clinical judgment”26 or “decided on an individual basis.”8

This marked variation in practice highlights a lack of evidence for an optimal compression strategy post EVTA. With no clear agreement between vascular units from both a clinical and academic perspective, and indeed from national and international guidelines, and the disparity not improving over time, it would be prudent to reexamine the evidence specific to compression regimens post EVTA to determine if this practice confers any benefits to patients, and if perhaps the benefit differs depending on the energy source of the interventional modality.

Evidence post EVLA

In the current literature, 3 RCTs have considered the impact of different compression regimens on clinical and patient reported outcomes after EVLA.17-19 Whereas 2 other RCTs24,25 included EVLA as a treatment option, most patients in these RCTs underwent RFA, and the outcomes from these trials will be considered in the next section.

The evidence surrounding compression post EVLA largely showed isolated improvements in postoperative pain, with little impact on other clinical and patient-reported outcomes. In one RCT, 111 patients (clinical, etiologic, anatomic, pathophysiologic classification [CEAP] C2-4) underwent EVLA treatment followed by a compression regimen of either 24-hours bandaging only, or 24-hours bandaging followed by 2 weeks of compression stockings. When measuring time taken to return to daily activity or work, there were no significant differences between the groups.18 This was also reflected in another RCT that randomized 400 varicose veins (CEAP C2) patients, with the two groups either using stockings for 12 hours or using stockings for 2 weeks. This RCT showed no difference in the average time taken to return to work as well.19

In these 2 RCTs, patients also did not report any significant differences in HRQOL improvements associated with the different compression regimens, as measured using the Aberdeen Varicose Vein Questionnaire (AVVQ)18,19 or the RAND 36-Item Health Survey.18 In the remaining RCT, 93 patients were randomized into wearing stockings for 48 hours or continuously for 7 days. In contrast to the findings from the other 2 trials, patients who wore the stockings for 7 days showed better Short Form-36 physical functioning and vitality scores than those who only wore them for 48 hours. This HRQOL benefit, however, was short-lived, with no significant difference found at 6-week follow-up.17

When considering pain, all 3 studies showed statistically significant improvement in pain scores in patients who were randomized to a longer duration of compression-stocking use. However, this positive impact on pain only lasted up to 7 days postoperatively, with no longer-term differences when patients were followed-up at 2 weeks19 and 6 weeks.17,18 As a surrogate measure for postoperative pain, 1 study also measured analgesia use. This study showed that while the extended compression group reported lower pain at 1-week follow-up, this group also used significantly greater quantities of paracetamol over the course of the 6-week study, although nonsteroidal anti-inflammatorydrug use was similar.18

Evidence post RFA

Considering compression regimens post RFA, 6 RCTs have been identified in the literature.20-25 These RCTs again consider a range of clinical and patient-reported outcomes, observing how different compression regimens affect these results. Five of the RCTs considered the impact of different durations of compression,20-22,24,25 whereas the remaining trial compared different types of compression, comparing leg sleeves with stockings.23

Once again, the RCTs examining compression post RFA showed no significant impact on most clinical or patientreported outcomes. Three studies observed the impact that compression regimens had on HRQOL. The largest of the 3 randomized 204 patients (CEAP C2-5), comparingEuroQol-5 dimension (EQ-5D), AVVQ, and ChronIc Venous Insufficiency Quality of Life Questionnaire 14-item (CIVIQ-14) scores between groups wearing compression for 1 week versus no compression after an initial 24 hours of wearing bandages. Whereas both groups showed improvement in both generic and disease-specific HRQOL, these improvements were not statistically different between the groups.25 This was also seen in an RCT that compared wearing stockings for 7 days versus no compression therapy, with 177 patients (CEAP C2-4) showing no differences in AVVQ scores at 6-month follow-up.21 In the last study that compared compression type (sleeves versus stockings) in 187 patients (CEAP C2-4), CIVIQ-20 score improvements were similar between comparison arms.23 Furthermore, no significant differences in time taken to return to work or usual activities were shown in 3 RCTs.20,21,25 Finally, whereas clinical severity scores were shown to be improved post RFA intervention in 3 RCTs, these improvements were not statistically different or related to changes in compression regimens.22,24,25

Interestingly, unlike the patients who were treated with EVLA, of the 5 RCTs that considered pain as an end point, 4 failed to show any significant difference in pain relief at all time points measured,20-22,24 unlike the benefit of pain improvement at 1 week shown in the EVLA studies. In an RCT that compared 101 patients (CEAP C2-4) randomized to 72 hours versus 4 hours of compression-stocking use, postoperative pain was not improved by a longer duration of compression at 3- and 14-day follow-up.20 Extending compression duration failed to show benefit as well. A study randomizing 100 patients (C2-6) into 2 arms comparing no compression with wearing compression stockings for 4 weeks showed no significant difference in pain scores at 12- to 14-week follow-up.22 Whereas this study’s finding would be consistent with the diminishing impact of pain relief seen after 1 week in the EVLA cohort, 2 other RCTs observed pain outcomes at 1 week24 and 10- days follow-up,21 both showing no improvements in pain relief with longer durations of compression. Only 1 RCT showed an association between longer compression and better pain improvement at 2 to 5 days postoperatively, but once again showed no lasting benefit with no significant difference in median pain scores over 1 to 10 days after EVTA intervention. This study, however, showed that there was no difference in analgesia use between groups, suggesting that there was a potential benefit to pain relief with a longer duration of compression post EVTA.25

Discussion

In recent years, 2 systematic reviews have considered these questions surrounding post EVTA compression, examining the results from the trials discussed above.27,28 Both reviews recognized that the evidence supports extending compression past the initial 48 hours to improve short-term pain relief for up to 10 days postoperatively. Considering this result, the first review supported the use of compression postoperatively, suggesting that the effect it had on pain relief justified the practice.27 However, in view of the lack of improvements in HRQOL and complication rates, the authors of the more recent review felt that the discomfort and difficulty of applying compression therapies outweighed the slight benefits to pain relief that they identified in their meta-analysis.28 Unfortunately, most studies included in that review failed to report on compliance; it would be hasty to draw such conclusions based on anecdotal experience, and it would behoove future studies to include this as an outcome measure.

One major source of heterogeneity in such trials revolves around the postoperative analgesia regimen used. Of the 9 RCTs discussed in this review, only 4 reported specifically on the use of analgesia post EVTA.18,19,21,25 One noted that no analgesia was prescribed but failed to determine if there was any over-the-counter simple analgesia used by patients in either comparison arm.19 Another noted that whereas the group that underwent a longer duration of compression showed improved pain relief, this was potentially confounded by the higher use of paracetamol seen in that patient population (although NSAID use was similar).18 Two other studies documented similar analgesia use between treatment arms, but despite this, one study showed improved pain relief with longer compression duration,25 while the other showed no difference between groups.21 This raises a potential cost-benefit question regarding compression therapies–if an appropriate analgesia regimen is recommended for patients post EVTA, this might represent a more cost-effective method of improving short-term postoperative pain.

Additionally, in clinical practice, EVTA is often not performed in isolation and may be combined with other techniques, such as foam sclerotherapy, phlebectomies, or multiple stab avulsions. A previous systematic review looking at postsclerotherapy compression qualitatively identified potential benefits of longer duration and higher grades of compression on postoperative complications (including pain) and wound healing (including those from concomitantphlebectomies). This benefit, however, was once again limited to short-term follow-up.29 In the 2 RCTs that included patients that underwent concomitant phlebectomies with RFA treatment of the truncal veins, one showed no difference in pain relief with varying compression type,23 whereas the other showed improvement in pain scores with a longer duration of compression stockings.25 Combining multiple treatment modalities is essential in clinical practice due to the various clinical presentations and patterns of refluxing veins that clinicians encounter. Personalizing compression regimens may be essential to maximize the benefits it confers while minimizing the discomfort it might impose.

Finally, this review has provided an opportunity for a closer look at the evidence, with the benefit of subdividing the published trials according to the 2 different modalities of energy used. Studies have shown that pain levels are significantly lower in patients whose varicose veins are treated with RFA than in those ablated using lasers.30 This may explain why the analgesic benefits of compression post EVLA were more pronounced than that of the RFA trials. It must be noted that improvements in EVLA devices have shown reduced postprocedural pain, and this observation may not hold true in trials with these newer devices.

Conclusions

Despite a significant number of trials over the last decade, compression regimens post EVTA remain heterogeneous. The extent of their benefits remains muddled by this heterogeneity, with current studies suggesting a benefit to short-term pain relief. This benefit, however, may potentially be negated should an appropriate postoperative analgesic regimen be employed. Current trials also suggest a greater benefit for compression post EVLA than post RFA; this may also be less significant with development of newer devices. It is unlikely that offering compression post EVTA for more than 7 days would be effective at providing any benefits to patients, but further clarification is required to determine if compression type and duration should be personalized to target specific groups of patients, or if any compression is required at all.

1. Lurie F, Passman M, Meisner M, et al. The 2020 update of the CEAP classification system and reporting standards. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2020;8(3):342-352.

2. Carradice D, Mazari FQK, Samuel N, Allgar V, Hatfield J, Chetter IC. Modelling the effect of venous disease on quality of life. Br J Surg. 2011;98(8):1089-1098.

3. Andreozzi GM, Cordova RM, Scomparin A, et al. Quality of life in chronic venous insufficiency. An Italian pilot study of the Triveneto Region. Int Angiol J Int Union Angiol. 2005;24(3):272-277.

4. Evans CJ, Fowkes FG, Ruckley CV, Lee AJ. Prevalence of varicose veins and chronic venous insufficiency in men and women in the general population: Edinburgh Vein Study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1999;53(3):149-153.

5. Gohel MS, Mora MSc J, Szigeti M, et al. Long-term Clinical and Cost-effectiveness of Early Endovenous Ablation in Venous Ulceration: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Surg. 2020;155(12):1113-1121.

6. Tassie E, Scotland G, Brittenden J, et al. Cost-effectiveness of ultrasoundguided foam sclerotherapy, endovenous laser ablation or surgery as treatment for primary varicose veins from the randomized CLASS trial. Br J Surg. 2014;101(12):1532-1540.

7. Gohel M. Which treatments are costeffective in the management of varicose veins? Phlebology. 2013;28(suppl 1): 153-157.

8. Maeseneer MGD, Kakkos SK, Aherne T, et al. European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS) 2022 Clinical Practice Guidelines on the Management of Chronic Venous Disease of the Lower Limbs. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg [Internet]. Published January 11, 2022. Accessed February 5, 2022. https://www.ejves.com/article/S1078- 5884(21)00979-5/fulltext

9. Marsden G, Perry M, Kelley K, Davies AH. Diagnosis and management of varicose veins in the legs: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ. 2013 Jul 24;347:f4279. doi:10.1136/bmj.f4279.

10. Reich-Schupke S, Murmann F, Altmeyer P, Stücker M. Quality of life and patients’ view of compression therapy. Int Angiol J Int Union Angiol. 2009;28(5):385-393.

11. Michaels JA, Campbell WB, Brazier JE, et al. Randomised clinical trial, observational study and assessment of cost-effectiveness of the treatment of varicose veins (REACTIV trial). Health Technol Assess Winch Engl. 2006;10(13):1-196, iii-iv.

12. Shingler S, Robertson L, Boghossian S, Stewart M. Compression stockings for the initial treatment of varicose veins in patients without venous ulceration. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;12:CD008819.

13. Lim CS, Davies AH. Graduated compression stockings. CMAJ Can Med Assoc J. 2014;186(10):E391-E398.

14. El-Sheikha J, Nandhra S, Carradice D, et al. Compression regimes after endovenous ablation for superficial venous insufficiency – a survey of members of the Vascular Society of Great Britain and Ireland. Phlebology. 2016;31(1):16-22.

15. El-Sheikha J, Carradice D, Nandhra S, et al. Systematic review of compression following treatment for varicose veins. Br J Surg. 2015;102(7):719-725.

16. El-Sheikha J, Carradice D, Nandhra S, et al. A systematic review of the compression regimes used in randomised clinical trials following endovenous ablation. Phlebology. 2017;32(4):256-271.

17. Bakker NA, Schieven LW, Bruins RMG, van den Berg M, Hissink RJ. Compression Stockings after Endovenous Laser Ablation of the Great Saphenous Vein: a prospective randomized controlled trial. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2013;46(5):588-592.

18. Elderman JH, Krasznai AG, Voogd AC, Hulsewé KWE, Sikkink CJJM. Role of compression stockings after endovenous laser therapy for primary varicosis. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2014;2(3):289-296.

19. Ye K, Wang R, Qin J, et al. Post-operative Benefit of Compression Therapy after Endovenous Laser Ablation for Uncomplicated Varicose Veins: a randomised clinical trial. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2016;52(6):847-853.

20. Krasznai A, Sigterman T, Troquay S, et al. A randomised controlled trial comparing compression therapy after radiofrequency ablation for primary great saphenous vein incompetence. Phlebology. 2016;31(2):118-124.

21. Pihlaja T, Romsi P, Ohtonen P, Jounila J, Pokela M. Post-procedural Compression vs. No Compression After Radiofrequency Ablation and Concomitant Foam Sclerotherapy of Varicose Veins: a randomised controlled non-inferiority trial. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2020;59(1):73-80.

22. Onwudike M, Abbas K, Thompson P, McElvenny DM. Editor’s Choice – Role of Compression After Radiofrequency Ablation of Varicose Veins: a randomised controlled trial. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2020;60(1):108-117.

23. Zolotukhin I, Demekhova M, Ilyukhin E, et al. A randomized trial of class II compression sleeves for full legs versus stockings after thermal ablation with phlebectomy. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2021;9(5):1235-1240.

24. Ayo D, Blumberg SN, Rockman CR, et al. Compression versus No Compression after Endovenous Ablation of the Great Saphenous Vein: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Vasc Surg. 2017;38:72-77.

25. Bootun R, Belramman A, Bolton- Saghdaoui L, Lane TRA, Riga C, Davies AH. Randomized Controlled Trial of Compression After Endovenous Thermal Ablation of Varicose Veins (COMETA Trial). Ann Surg. 2021;273(2):232-239.

26. Lurie F, Lal BK, Antignani PL, et al. Compression therapy after invasive treatment of superficial veins of the lower extremities: clinical practice guidelines of the American Venous Forum, Society for Vascular Surgery, American College of Phlebology, Society for Vascular Medicine, and International Union of Phlebology. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2019;7(1):17-28.

27. Ma F, Xu H, Zhang J, et al. Compression therapy following endovenous thermal ablation of varicose veins: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Vasc Surg. 2022;80:302-312.

28. Hu H, Wang J, Wu Z, Liu Y, Ma Y, Zhao J. No Benefit of Wearing Compression Stockings after Endovenous Thermal Ablation of Varicose Veins: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2022;63(1):103-111.

29. Tan MKH, Salim S, Onida S, Davies AH. Postsclerotherapy compression: a systematic review. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2021;9(1):264-274.

30. Shepherd AC, Gohel MS, Lim CS, Hamish M, Davies AH. Pain Following 980-nm Endovenous Laser Ablation and Segmental Radiofrequency Ablation for Varicose Veins: a prospective observational study. Vasc Endovascular Surg. 2010;44(3):212-216.