Lymphedema-angiodysplasia syndrome: a prodigal form of lymphatic malformation

MD, PhD, FACS

Medicine & Samsung Medical Center

Seoul, Korea

School of Medicine

ABSTRACT

Primary lymphedema is a clinical outcome of lymphatic malformation (LM) following developmental arrest in the latter stage of embryogenesis, and known as the truncular (T) form. LM caused by developmental arrest in the earlier stage of lymphangiogenesis, often termed cystic/cavernous lymphangioma, is referred to as the extratruncular (ET) form. Primary lymphedema has been managed as a chronic lymphedema together with secondary lymphedema, although its etiopathophysiology is entirely different from that of secondary lymphedema. However, lately primary lymphedema has been recognized as being related to the ET form of LM, and new the classification of congenital vascular malformation (CVM) has finally included the ET and T forms of LM as types of CVM. The ET form of LM, known as cavernous and/or cystic lymphangioma, and the T form, known as primary lymphedema, are now considered as members of the LM family, which develop at different stages of lymphangiogenesis. A retrospective review of the clinical data of a total 254 patients with LM (186 T form and 68 ET form) has therefore been done, aiming to provide a proper basis for advanced management of the T and ET forms as aspects of LM, based on newly developed concepts.

Patients and methods: The diagnosis of LM was made using various combinations of different noninvasive diagnostic tests: MRI and/or CT, Tc-99m RBC wholebody blood pool scintigraphy, Tc-99m antimony sulfide colloid lymphoscintigraphy, and duplex ultrasonography. For the 186 T form LMs, diagnosed following proper clinical/laboratory staging, treatment was instituted using various combinations of MLD (manual lymphatic drainage)-based CDP (complex decongestive therapy) and SIPC (sequential intermittent pneumatic compression)-based compression therapy depending upon the clinical stage of the chronic lymphedema. Various surgical therapies, either reconstructive or ablative, were also implemented as adjunct therapies for primary lymphedema to improve the efficiency of CDP-based therapy in the earlier clinical stage, and compression therapy in the later stage. For the 68 ET LMs, the best treatment option was selected per indication, from the various combinations of sclerotherapy and/or surgical therapy; OK-432 sclerotherapy as the option of choice as a primary therapy and absolute ethanol sclerotherapy and/or a surgical excision as the second option, preferably after the first option had failed. The T form was evaluated using clinical and laboratory assessments of chronic lymphedema status every 6 months including treatment response, either medical (physical) only or surgical combined. The evaluation of the ET form was made by duplex sonography and MRI where feasible, and by clinical assessment.

Results: Of 68 ET form patients, 51 pediatric patients, treated with OK-432 sclerotherapy for a total of 108 sessions, showed satisfactory lesion control in the majority of cases (84.3%): a complete to marked shrinkage in 88.9% of the limited cystic type. Seventeen ET forms of the total 68 underwent preoperative embolo/sclerotherapy and subsequent surgical excision, which gave clinically good to excellent results for 14 of the 17. One hundred and eighty-six T form patients, treated for chronic lymphedema, showed an excellent to good response in the majority in clinical stages I and II, and a good to fair response in stages III and IV. Long-term results of additional surgical therapy, either reconstructive or ablative, on 8 patients were totally dependent on patent compliance to maintain postoperative CDP/compression therapy-based maintenance care.

Conclusion: Conventional management of the T form of LM as for primary lymphedema is limited even with supplemental surgical therapy. The treatment of the ET form of LM, especially of the infiltrating cavernous type, is also limited by conventional sclerotherapy. Therefore, the overall management of LMs should be further improved by adopting an innovative genetic approach to the correction of (lymph) angiogenesis and/or vasculogenesis defects.

INTRODUCTION

Primary lymphedema is a form of lymphatic malformation (LM), and shares the background of other congenital vascular malformations (CVMs), as a birth defect that affects only the lymphatic circulation system of the three (peripheral) vascular systems, ie, arterial, venous, and lymphatic systems.1,2

Primary lymphedema3 is a clinical outcome of LM following developmental arrest in the latter stage of embryogenesis, the so-called truncular (T) LM form.1,2,4 LM caused by developmental arrest in the earlier stage of lymphangiogenesis, often termed cystic/cavernous lymphangioma, is referred to as the extratruncular (ET) LM form, to delineate its mesenchymal embryologic characteristics.1,2,5

Primary lymphedema has been unintentionally ignored by the majority of CVM specialists, and has been managed as a chronic lymphedema by lymphologists3,6,7 for decades together with secondary lymphedema, although its etiopathophysiology is entirely different from that of secondary lymphedema. However, lately, primary lymphedema has been recognized as being related to the ET form of LM, although the relation between it and secondary lymphedema should be retained, especially from the management point of view.5

The concept of CVMs based on new classification, new diagnostic technologies, and the novel multidisciplinary team approach have provided solid clues that explain many of the perplexities associated with CVMs, also known as angiodysplasia.8 The modified Hamburg classification, based on the original Hamburg consensus of 1988, finally included the ET and T forms of LM as types of CVM. The ET form of LM, known as cavernous and/or cystic lymphangioma, and the T form, known as primary lymphedema, are now be considered as members of the LM family, that develop at different stages of lymphangiogenesis.1,2 This new concept of LM as a vascular malformation enables patients to benefit from the conceptual advances made in CVM treatment, and facilitates the restructuring of old perceptions to accommodate the style of management required to address its causative (lymph)angiogenic and vasculogenic abnormalities at the biomolecular level.9,10

AIM

A retrospective review of the clinical data of a total 254 patients with predominant LMs (186 T form and 68 ET form), registered at the CVM Clinic and the Lymphedema Clinic of Samsung Medical Center & Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea, during the period September 1994 to December 2000, was conducted. Our aim was to provide proper basis for approaching the management of the T and ET forms as aspects of LM, and subsequently for their advanced management based on newly developed concepts concerning the genetic defects responsible for developmental arrest at different stages of embryonic life.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Diagnosis

One hundred and eighty-six T form LMs, registered at the Lymphedema Clinic as primary lymphedema, underwent clinical and laboratory evaluation for the proper clinical and laboratory staging of clinical lymphedema in order to later assign pertinent therapy. The T form was also reevaluated as a vascular malformation through separated registration at the CVM Clinic, together with the ET form of LM as well as various other CVMs. This T form of LM was further investigated for differential diagnosis, especially with the combined form of CVM, which exists mainly as the hemolymphatic malformation (HLM). HLM represents a mixed condition of venous malformation (VM) and LM in ET form as the major component.11,12

A total of 68 ET LM cases, registered at the CVM Clinic, also underwent a laboratory evaluation specifically designed for LM, in addition to the basic tests required for all the CVMs to differentiate CVMs from each other and obtain crucial information of the LM status either as a “pure” form or a “mixed” form with other CVM (eg, HLM).

The diagnosis of LM, either of the T or ET form, was made using various combinations of different noninvasive diagnostic tests8,11,13: MRI and/or CT, Tc-99m RBC wholebody blood pool scintigraphy, Tc-99m antimony sulfide colloid lymphoscintigraphy,14,15 and duplex ultrasonography, and occasionally with added optional MR and/or ultrasound lymphangiography (Figures 1 and 2). However, diagnosis seldom required an invasive study for the differential diagnosis of CVM type by direct puncture lymphangiography or conventional angiography. The simultaneous assessment of venous function status during the LM diagnostic procedure was included as a mandatory requirement.

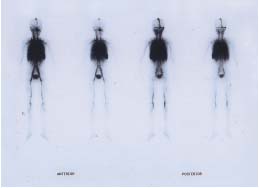

Figure 1. A to E. Truncular (T) form of lymphatic malformation (LM) with multiple involvement throughout the body.

A. Clinical appearance of primary lymphedema along the right

upper extremity (forearm and hand) due to a T form LM.

B. Clinical appearance of primary lymphedema along the left lower

extremity due to a T form LM, with simultaneous involvement of

the upper extremity.

C. WBBPS* finding of no abnormal blood pool over the LM-affected

limbs, ruling out combined VM*.

D. Lymphoscintigraphic findings of a lack of normal lymphatic system

development, due to T form VM, affecting the right upper extremity.

E. Lymphoscintigraphic finding of reduced lymphatic function

along the left lower extremity due to incomplete development of the

normal lymph node-collecting lymph vessel system.

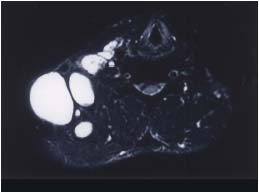

Figure 2. A, B. Extratruncular form (ET) form of a multiple cystic

lymphatic malformation (LM).

A. Clinical appearance of a superficially located ET LM with recurrent

leakage and infection.

B. MRI finding of an ET form of multiple cystic LM affecting the

right neck, shoulder, and anterior chest wall.

Treatment

For the 186 T form LMs, diagnosed following proper clinical/laboratory staging, treatment was instituted using various combinations of MLD (manual lymphatic drainage)-based CDP (complex decongestive therapy) and SIPC (sequential intermittent pneumatic compression)- based compression therapy depending upon the clinical stage of the chronic lymphedema.7,16

Various surgical therapies,5,17,18 either reconstructive or ablative, originally designed for secondary lymphedema, were also implemented as adjunctive therapies for primary lymphedema to improve the efficiency of CDP-based therapy at the earlier clinical stage, and compression therapy in the later stage, when physical therapy failed to provide an adequate response, despite maximum available treatment, or the disease progressed. However, the decision to select a candidate for further surgery was made upon consensus by the multidisciplinary team, based on strict result assessment; in particular, patient compliance was the most critical factor. Good compliance was a mandatory prerequisite for all surgical candidates, since postoperative maintenance relies heavily on a self-initiated home-based maintenance program under periodic supervision.

For the 68 ET LMs, the best treatment option was selected per indication, once a proper diagnosis had been made, from the various combinations of sclerotherapy and/or surgical therapy when indicated.5,11,18 However, OK-432 sclerotherapy was implemented as the option of choice as a primary therapy whenever and wherever possible. Absolute ethanol sclerotherapy and/or a surgical excision were selected as the second option, preferably after the first option had failed. Recurrent and/or deeply seated lesions, preferably of the cystic type, were generally treated with ethanol, while de novo and/or superficially seated lesions were treated by OK-432 sclerotherapy. Multisession sclerotherapy either with OK-432 or high concentration ethanol (>75%) were performed either as independent therapies, mainly for the cystic type, or as adjunctive therapy, mainly for the cavernous type of ET form perioperatively.

Treatment of the 68 ET LMs was usually indicated by a cosmetically severe deformity (eg, face) and/or functional disability (eg, hand, foot, wrist, ankle, etc).5,11 Urgent treatment was also indicated for 9 lesions located near vital structures or organs (eg, airway), threatening critical functions like breathing, vision, hearing, and eating, or to lesions accompanied by complications (eg, bleeding by the mixed venous component, lymph leaking, and recurrent erysipelas/cellulitis, etc).

RESULTS

ET form

Of 68 patients confirmed for the pure ET form of LM with no other vascular malformation combined, 51 pediatric patients were selected for treatment with OK-432 sclerotherapy and underwent a total of 108 sessions. Its long-term results with an average follow-up period of over 24 months showed satisfactory lesion control in the majority (84.3%): excellent response showing a complete to marked shrinkage in 88.9% of the limited cystic type (40/45), and in 50% (3/6) of the diffuse infiltrating cavernous type (Figure 3).

Seventeen ET form (9 infiltrating type; 8 limited type) of total 68 underwent preoperative OK-432, ethanol and/or N-butylcyanoacrylate embolo/sclerotherapy and subsequent surgical excision, which gave clinically good to excellent results for 14 of the 17 (Figure 4). No evidence of recurrence for all 17 LM lesions has emerged over a minimum follow-up of 24 months.

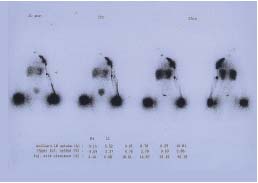

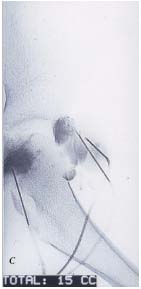

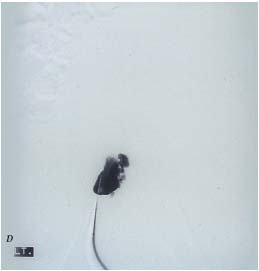

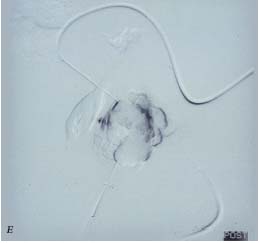

Figure 3. Ethanol and OK-432 sclerotherapy of extratruncular (ET)

lesions.

A. Clinical appearance of an ET lymphatic malformation (LM)

affecting the left groin with recurrent infection.

B. MRI finding (sagittal view) of the infiltrating ET form of a

mixed cystic and cavernous type LM.

C. Angiographic finding by ethanol sclerotherapy of a deeply seated

cystic lesion.

D and E. Angiographic findings of OK-432 sclerotherapy of a

superficially locating cystic lesion (D) and its subsequent

satisfactory control (E).

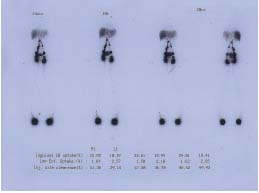

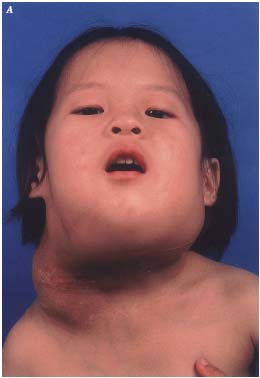

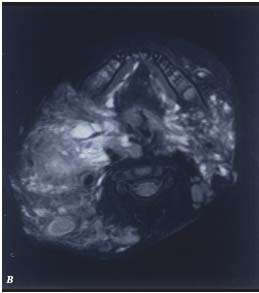

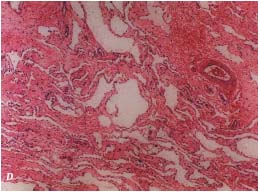

Figure 4. Surgical therapy combined with preoperative

sclerotherapy using OK-432 for a recurrent extratruncular (ET)

lymphatic malformation (LM) lesion following a poor

surgical strategy.

A. Clinical appearance of a recurrent lesion over the right neck as a

diffuse swelling along the incision scar.

B. MRI finding of the extensive nature of an ET LM, involving

the entire soft tissue of the right neck and extending to the

retropharyngeal and left submandibular regions.

C. Operative finding of the lesion together with the surgical specimen,

which was excised safely following preoperative multisession

OK-432 sclerotherapy.

D. Histopathological finding of the ET form of an LM.

T form

One hundred and eighty-six T form (mostly clinical stage II of primary lymphedema) were treated for chronic lymphedema using various combinations of CDP and/or compression therapy depending upon the clinical/laboratory stage. They cases have shown an excellent to good response in the majority in clinical stages I and II (115/130) and a lower level of improvement with a good to fair response in stages III and IV (21/56), following initial inhospital care. Long-term maintenance of the initial treatment results through a self-initiated home-maintenance care program up to an average of 48 months of follow-up period has been excellent for 46, good to fair for 85, and poor for 38, with slow progress from the initial clinical stage when CDP was started; rapid progression with recurrent sepsis was observed in 17 of the 186 patients with a loss to follow-up for 17 patients.

Long-term results of additional surgical therapy, either reconstructive or ablative (4 venolymphatic anastomotic reconstruction, and 8 excisional surgery on 4 patients) on 8 patients to the end point of the follow-up (48 months) were found to be totally dependent on patent compliance to maintain postoperative CDP/compression therapybased maintenance care: only good to fair results for 4 patients, and good compliance in 8 patients.

DISCUSSION

Diagnosis

The ET form of LM is due to an embryonicl remnant,2,4 which is believed to be involuted when organogenesis moves into the T stage of embryonal life, but which remains at birth. This ET form of LM is therefore the final outcome of developmental arrest during earlier embryonic life at the plexular and/or reticular stages, and retains its evolutive potential (omnipotential evolutibility), a characteristic of mesenchymal cells of mesodermal origin (eg, angioblasts). Moreover, whenever triggered by conditions like trauma, pregnancy, surgery, or hormonal therapy, they regrow uncontrollably. Therefore, like the ET form of all other CVMs, the ET form of LM also presents this clinically serious issue of the risk of continuous growth or recurrence after treatment.

The T form of LM, often known as primary lymphedema, however, does not have the evolutive potential of the ET form, because it is the result of developmental arrest at a later stage of embryonic life, during the T stage following the reticular stage. It is the consequence of a failure to develop a normal lymphnodolymphatic vessel system at the T stage, and therefore, it often manifests as aplasia, hypoplasia, hyperplasia, obstruction, and/or dilatation of the lymphatic vessels, with/without combined lymphnododysplasia.

Lymphatic malformations may exist alone as independent vascular defects or may exist with various other vascular defects, which produce addition hemodynamic effects due to their interactions, ie, in addition to their individual functions.1 For example, the ET and T forms of LM are often colocalized and affect each other markedly in terms of lymphatic function, especially in combined forms of vascular malformations, like HLM, which is often known as Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome. Both ET and T form LMs and have a close hemodynamic relationship with the venous system, especially combined with VM when they can profoundly affect each other functionally. Increasing evidence indicates a negative impact of VM on LM, especially following the aggressive treatment of the VM component of HLM (eg, marginal vein resection), but of a positive impact on LM when it is combined with micro-AVshunting AVM lesions that are properly managed.

Therefore, the ET form of LM, often called cystic or cavernous lymphangioma, has to be carefully evaluated for possible combinations with the T form of LM and with other types of CVM, ie, venous, AV shunting, capillary, and hemolymphatic malformations, for optimal clinical management, since there is a reasonable chance of it being accompanied by other kinds of VMs.

Treatment

The ET form of LM is not a life- or limb-threatening condition in general. Therefore, treatment modalities with a high risk of complications and/or morbidity (eg, absolute ethanol sclerotherapy) should not be considered for initial treatment, even if long-term results (eg, recurrence) might be improved.26 Safer, less risky methods (eg, OK-432) are preferred for initial treatment, even given the higher risk of recurrence versus the stronger agent.

However, sclerotherapy, either with ethanol or OK-432, has not been uniformly successful in the treatment of the cavernous ET form in contrast to the cystic type, and attempts to improve therapeutic results in this group by using combined surgical/sclerotherapy have produced promising results, although further study is warranted to prove the accuracy of this clinical impression.11 The ET form of LM also carries the inherent problem of recurrence with significant morbidity regardless of the treatment modality, especially in cases of infiltrating cavernous ET form.

Our experiences with the T form of LM with CDP and/or compression therapy as a basic form of lymphedema clinical management have not been uniformly successful, especially in advanced clinical stage cases, mainly due to reduced patient compliance to a lifetime commitment to this incurable disease, and due to the ignorance of medical personnel who fail to encourage patients to maintain compliance. Additional surgical therapy to supplement this physiotherapy-based treatment of the T form has also not been uniformly successful, due to a failure to maintain proper postoperative physiotherapy, although it should be added that our experiences with primary lymphedema are limited.

Therefore, the need for a modality capable of dealing with both the T and ET forms of LM at the genetic level is urgently required. Rapid advances in genetic engineering will hopefully open up a new chapter in the treatment of these conditions through proper gene manipulation in the near future.

CONCLUSION

Conventional management of the T form of LM by CDP/compression therapy, as for primary lymphedema, is limited, even with supplemental surgical therapy. The treatment of the ET form of LM, especially of the localized infiltrating cavernous type, is also limited by conventional sclerotherapy with or without combined preoperative sclerotherapy.

Therefore, the overall management of LMs should be further improved by adopted an innovative genetic approach to the correction of (lymph) angiogenesis and/or vasculogenesis defects. The proper identification and characterization of those genes responsible for vascular malformations (CVM) is warranted as a first step toward a gene therapy for the T and ET forms of LM.

Acknowledgments

The author expresses the gratitude to each member of the multidisciplinary team of the Congenital Vascular Malformation Clinic and the Lymphedema Clinic, Vascular Center of Samsung Medical Center, and to EunKyung Cho, administrative manager for her devotion to the manuscript preparation, EunSook Kim, nurse coordinator, JiYoung Moon, research coordinator, and to MiAe Han, clinical nurse, for their assistance.

REFERENCES

2. Bastide G, Lefebvre D. Anatomy and organogenesis and vascular malformations. In: Belov ST, Loose DA, Weber J, eds. Vascular Malformations. Reinbek: Einhorn- Presse Verlag GmbH; 1989;20-22.

3. Foldi E, Foldi M, Weissletter H. Conservative treatment of lymphedema of the limbs. Angiology. 1985;36:171-180.

4. Woolard HH. The development of the principal arterial stems in the forelimb of the pig. Contrib Embryol. 1922;14:139-154.

5. Lee BB, Kim DI, Hwang JH, Lee KW. Contemporary management of chronic lymphedema – personal experiences. Lymphology. 2002;35(suppl):450-455.

6. Hwang JH, Lee KW, Chang DY, et al. Complex physical therapy for lymphedema. J Kor Acad Rehab Med. 1998;22:224-229.

7. Casley-Smith JR, Mason MR, Morgan RG, et al. Complex physical therapy for the lymphedematous leg. Int J Angiol. 1995;4:134-142.

8. Lee BB, Bergan JJ. Advanced management of congenital vascular malformations: a multidisciplinary approach. Cardiovasc Surg. 2002;10:523-533.

9. Witte MH. Genetic alterations in lymphedema. Lymphology. 1998;31:19-25.

10.Witte MH, Way DL, Witte CL, Bernas M. Lymphangiogenesis: mechanisms, significance and clinical implications. In: Goldberg ID, Rosen EM, eds. Regulation of Angiogenesis. Basel, Switzerland: Birkhäuser Verlag; 1996;65-112.

11. Lee BB, Seo JM, Hwang JH, et al. Current concepts in lymphatic malformation (LM). J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2004. In press.

12. Lee BB. Advanced management of congenital vascular malformation (CVM). Int Angiol. 2002;21:209-213.

13. Lee BB, Kim DI, Huh S, et al. New experiences with absolute ethanol sclerotherapy in the management of a complex form of congenital venous malformation. J Vasc Surg. 2001;33:764-772.

14. Choi JY, Hwang JH, Park JM, et al. Risk assessment of dermatolymphangioadenitis by lymphoscintigraphy in patients with lower extremity lymphedema. Kor J Nucl Med. 1999;33:143-151.

15. Choi JY, Lee KH, Kim SE, Kim BT, Hwang JH, Lee BB. Quantitative lymphoscintigraphy in post-mastectomy lymphedema: correlation with circumferential measurements (abstract). Kor J Nucl Med. 1997;3:262.

16. Hwang JH, Kwon JY, Lee KW, et al. Changes in lymphatic function after complex physical therapy for lymphedema. Lymphology. 1999;32:15-21.

17. Campisi C, Boccardo F. Frontiers in lymphatic surgery. Microsurgery. 1998;18:462-471.

18. Kim DI, Huh S, Lee SJ, Hwang JH, Kim YI, Lee BB. Excision of subcutaneous tissue and deep muscle fascia for advanced lymphedema. Lymphology. 1998;31:190-194.