Medical treatment of pelvic congestion syndrome

Levent SAHIN2;

Sergey G. GAVRILOV3;

Zaza LAZARASHVILI4

of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Antalya,

Turkey

2 Kafkas School of Medicine, Departme

of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Kars,

Turkey

3 Leninskii Prospekt, Moscow, Russia

4 Chapidze Emergency Cardiovascular

Center, Tbilisi, Georgia

Abstract

Pelvic congestion syndrome (PCS) has no clear etiology and the diagnosis relies on precise investigation techniques. PCS patients present with chronic symptoms in the area of the pelvis, which may have various etiologies; therefore, before any treatment is administered, it is important to exclude other medical conditions that may cause similar symptoms. Treatment options include cognitive behavioral pain management using psychotherapy; medical management that combines pain relief and, if the pain has a cyclical component, hormone suppression; endovenous procedures, such as coil or foam sclerotherapy; and surgery. The choice of treatment depends on symptom severity and the presence of vulvar and lower limb varicose veins. Initially, a medical approach should be offered, reserving surgery for resistant cases and patients who present with side effects to the medical treatment. In the majority of women, medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA) or goserelin acetate effectively reduced pain and the size of the varicose veins. MPA and micronized purified flavonoid fraction provide short-term improvement, but no data are available on their long-term efficacy. Surgery has progressively been replaced by endovenous procedures with distal embolization of the refluxed veins using a coil and/or a foam sclerosant, and/ or by ballooning and stenting the iliac vein compression. Currently, no standard approach is available for the management of PCS; therefore, therapies should be individualized based on symptoms and the patient’s needs.

Introduction

Pelvic congestion syndrome (PCS) is described as “chronic symptoms, which may include pelvic pain, perineal heaviness, urgency of micturition, and post-coital pain, caused by ovarian and/or pelvic vein reflux and/or obstruction, and which may be associated with vulvar, perineal, and/or lower extremity varices.”1 PCS is a potential cause of chronic pelvic pain in women of childbearing age.2,3 Chronic pelvic pain accounts for 10% to 40% of all presentations to obstetrics and gynecology outpatient clinics.4,5

Pelvic pain among women is a common condition that may have various causes. The most common causes of pelvic pain not only include PCS, but also endometriosis, pelvic adhesions, atypical menstrual pain, urological problems, spastic colon syndrome, and psychosomatic disorders.4 Therefore, the diagnosis of PCS relies on precise investigation techniques. Once the diagnosis is made, the decision to treat PCS is based on the severity of the symptoms and the presence of vulvar and/or lower limb varices.6

PCS pathogenesis

PCS is a specific entity that is caused by both dilation of broad ligaments and ovarian plexus veins and an incompetent ovarian vein.7 It has been reported that PCS occurs in 10% of the general female population and ≈50% of women who have chronic pelvic pain.4,8 Pain secondary to pelvic congestion increases with fatigue, coitus, and conditions that increase intraabdominal pressure, such as walking, bending, heavy lifting, and prolonged sitting during the premenstrual period.9 Chronic pelvic pain is generally unilateral.8,10,11

Pelvic congestion is diagnosed mostly in multiparous women, while no cases have been reported in postmenopausal women. In multiparous women, PCS is associated with dilated pelvic varices with reduced venous clearance due to retrograde flow in an incompetent ovarian vein. Zehra Gültaply et al found an association between mean number of births and the presence of pelvic varices.9 During pregnancy, the ovarian vein dilates, permitting a 60-fold increase in blood flow, which is considered to be one of the most important causes of venous insufficiency.10,12

The venous congestion stretches over the inner surface of the ovarian vein, distorting both the endothelial and smooth muscle cells. It is postulated that kinking of the ovarian vein leads to venous stasis, flow reversal, and subsequent varicosities.13 Since the venoconstriction and occlusion of pelvic varicose veins by medical, surgical, or interventional radiological treatment results in an amelioration of the symptoms, PCS is suspected to occur as a result of gonadal dysfunction associated with mechanical factors.3,14,15 Therefore, this suggests that there is a relationship between PCS and endogenous estrogen levels because estrogen is known to weaken vein walls.13

PCS diagnosis

For most interventional radiologists who treat PCS patients, techniques, such as phlebography, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or magnetic resonance venography (MRV), and embolotherapy, are at the center of PCS diagnosis and treatment, but laparoscopy in women with chronic pelvic pain remains an alternative method of diagnosis. Chronic pelvic pain is a common clinical entity encountered in gynecology, but it is difficult to establish the true incidence of PCS, given the lack of standard diagnostic criteria and even of clinical suspicion in women with gynecological and urological symptoms. Therefore, the pathology is frequently underdiagnosed. According to the available literature, up to 10% of the general population have ovarian varices and 60% of people with ovarian varices may develop PCS.5,16

Since the symptoms are variable, the diagnosis of PCS is difficult. Even after making the diagnosis of pelvic varicosities, the treatment is not always successful and ends with patient dissatisfaction. The severity of symptoms is so variable that a standard therapy protocol is difficult to set up. It is essential that other medical conditions, which may cause similar symptoms, be excluded before any treatment is administered.

PCS treatment options

Treatment options for PCS remained elusive until recently due to controversial diagnostic methods and a poor understanding of its etiology, which ranges from a psychosomatic origin to vascular causes. There is no standard approach to manage PCS; therefore, therapies should be individualized based on symptoms and the patient’s needs. Although apparently effective treatments have been devised, it is not clear which could be considered the best option.17 Various medical and surgical options are available, but a biopsychosocial approach is paramount. A medical approach should be offered initially, reserving surgery for resistant cases and patients who present with side effects to the medical treatment.

Since Topolanski-Sierra first noted an association in the 1950s between chronic pelvic pain and ovarian and pelvic varices,18 many treatment modalities have been proposed. Medical management with hormone analogs and analgesics, surgical ligation of ovarian veins, hysterectomy with or without bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and transcatheter embolization have been described in the literature as treatment options for patients with PCS. However, another challenge in the above-mentioned treatments is differentiating patients with endometriosis, which is a common estrogen-dependent disorder in women with chronic pelvic pain, from patients with PCS. This challenge emphasizes the role of enlarged veins in the pathophysiology of pelvic congestion syndrome, which is also estrogen-dependent.

Medical treatment of PCS includes psychotherapy, analgesics, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, dihydroergotamine, progestins (contraceptives, hormone replacement therapy, danazol), gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists, and venoactive drugs.

Psychological approach

Women with PCS are often depressed and anxious, which is partly because they have symptoms for which the cause is often difficult to find. There are also pharmacological and physiological reasons for why they might suffer psychological stress. The venous congestion in PCS causes stretching and shear stress on the inner surface of the ovarian vein, which distorts both the endothelial and the smooth muscle cells. These cells respond by releasing vasodilator substances that include neuropeptide transmitters, such as substance P, neurokinin A, and neurokinin B. These neuropeptide transmitters play a key role in the regulation of emotions and they are an integral part of central nervous system pathways involved in psychological stress.17

Psychotropic drugs have been shown to be effective in treating chronic pelvic pain. Gabapentin and amitriptyline were used for this purpose. After 6, 12, and 24 months, pain relief was significantly better in patients receiving gabapentin either alone or in combination with amitriptyline than in patients receiving amitriptyline monotherapy.19 Side effects were lower in the gabapentin group than in the other two groups, the difference reached statistical significance after 3 months (P<0.05). This study showed that gabapentin alone or in combination with amitriptyline is better than amitriptyline alone in the treatment of female chronic pelvic pain.

Analgesics

Analgesics are a good first-line treatment, but symptoms should not be ignored if it is not completely effective or if pain recurs when treatment is stopped.

Dihydroergotamine

Reginald et al have shown that a 30% reduction in pain can be achieved following the intravenous administration of the selective vasoconstrictor, dihydroergotamine, and that this medication decreased congestion; however, as this effect is only transient, no therapeutic modality has been able to take advantage of this phenomenon.20 In addition, since dihydroergotamine has systemic vasoconstrictor properties, its clinical application would demand special caution due to the narrow therapeutic margin of safety.21

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are an acceptable first-line treatment because they provide a short-term solution and they may offer some relief while patients await further investigations or a more permanent treatment. However, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are not a long-term solution to the patient’s problem.17

Medical suppression of ovarian function

Medical suppression of ovarian function and hysterectomy with or without bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy have been described as potential alternatives, but are not widely used.22 Estrogen may have some vasodilatory effects, suggesting that hypoestrogenic states would result in symptom resolution.17 However, the studies have been small, meaning that firm conclusions cannot be drawn from these studies.

MPA

Medoxyprogesterone acetate (MPA), also known as 17α-hydroxy-6α-methylprogesterone acetate, is a steroidal progestin, a synthetic variant of the steroid hormone progesterone.23 It is used for contraception, hormone replacement therapy, treating endometriosis, and chemical castration.

MPA has been shown to relieve symptoms in approximately 40% of patients, and a combination of MPA and psychotherapy may be effective in around 60% of patients. However, in one study in which patients were assigned to receive either psychotherapy alone, MPA alone, MPA plus psychotherapy, or placebo, no overall significant effect of MPA or psychotherapy was found, but the combination of MPA and psychotherapy had an effect 9 months after the treatment ended.24 Weight gain and depression have been reported by patients who do not tolerate MPA.

MPA was also beneficial in 22 PCS patients both subjectively in terms of pain perception and objectively by assessing pelvic congestion using venography. In this study, 30 mg MPA taken for 6 months suppressed ovarian function.25 In 17 out of the 22 women, pelvic congestion was reduced as shown by venography, and in 16 women, this reduction was associated with an induction of amenorrhea, which suggests that effective ovarian suppression is an important component of successful treatment. In the 17 women who showed a reduction in the venogram score, there was a median change of 75% in the pain score vs 29% in the 5 women with no change in the venogram score (P<0.01).20,25 Oral MPA, given at a 50-mg daily dosage, was effective in reducing pain associated with endometriosis at the end of therapy, but the benefit was not sustained.26

Subcutaneous form of MPA: DMPA

Depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA) is a low-dose subcutaneous form of MPA that is injected at 150 mg/mL, and it provides efficacy, safety, and immediate onset of action. In a 12-month trial, DMPA depot (150 mg every 3 months) had effects equivalent to GnRH agonists.21 DMPA has significant long-term side effects (hypoestrogenic effects, such as hot flashes, bleeding changes, osteoporosis), even if these effects are less than those observed when using leuprolide acetate.27

Gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists

Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists have also been used for the treatment of PCS. An injectable GnRH agonist, also known as goserelin acetate (trade name Zoladex by AstraZeneca), is used to suppress production of the sex hormones testosterone and estrogen, particularly in the treatment of breast and prostate cancer.28

In a prospective randomized controlled trial, 47 patients diagnosed with PCS were treated with either goserelin acetate without add-back hormone replacement therapy or MPA for 6 months.29 Both treatments showed subjective and objective improvements in PCS, a reduction in anxiety levels, and an improvement in sexual satisfaction. However, at a 12-month follow-up after cessation of treatment, a statistical comparison of these agents confirmed a better outcome for goserelin acetate. The main side effects of MPA included weight gain and bloating, whereas the main side effect of GnRH analogs included symptoms of menopause.

Danazol

Danazol, a 17-ethinyl-testosterone derivative, is an antigonadotropic agent for the treatment of pelvic endometriosis30 that has been used as a medication for chronic pelvic pain associated with endometriosis. At a dose of 600 mg/day, danazol was effective for endometriosis-associated chronic pelvic pain.31 In 2005, the Chronic Pelvic Pain Working Group considered that hormone treatment for chronic pelvic pain of gynecologic origin, with oral contraceptives, progestins, danazol, and GnRH agonists, should be considered as the first-line treatment for many women, especially those with endometriosis.32

Contraceptive implant

Another hormone alternative in women with PCS is Implanon. The synthetic steroid Implanon is a single-rod, nonbiodegradable implant that contains and releases etonogestrel (3-keto-desogestrel), a progestin that is used as a long-term contraceptive method. Implanon blocks follicle stimulating hormone activity, which results in inhibition of ovulation. The implant provides long-term contraceptive efficacy for 3 years. Earlier studies have shown that Implanon suppresses follicular development and steroid production, thereby producing a state of hypoestrogenism.33,34 Thus, patients with pure PCS due to venous stasis may benefit from this kind of treatment. Several studies have demonstrated that Implanon, as a contraceptive method, was well tolerated, with excellent and reversible contraceptive efficacy.35 In addition, the use of Implanon in women with PCS obviates the need for repeated treatment where symptoms recur and for additional contraception.36

In a prospective open-label study in which 23 consecutive women who were complaining of chronic pelvic pain were randomly assigned to either a subcutaneous insertion of Implanon (12) or no treatment (11), Shokeir et al reported that an improvement in symptoms was observed throughout the 12 months among the Implanon group vs no treatment. The greatest changes in pain, assessed using either the visual analog scale or the verbal rating scale, were between the pretreatment scores and those after 6 months.37 This 1-year trial showed that Implanon is an effective hormone alternative for long-term treatment of properly selected patients with pure PCS-related pelvic pain.

One of the advantages of Implanon compared with MPA is that the patients regain their fertility more rapidly after discontinuation, often within 1 week.33,35

Venoactive drugs

Venoactive drugs, and, more specifically, the micronized purified flavonoid fraction (MPFF*), have been investigated for the treatment of PCS.38,39 These medications have a protective and tonic effect on the venous and capillary wall, which increases venous tone, improves lymphatic drainage, and reduces capillary hyperpermeability resulting in a reduction in venous stasis. MPFF has been widely studied in the treatment of patients with symptomatic chronic venous disease.40,41

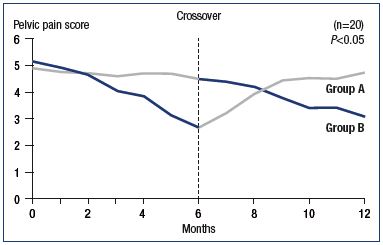

Simsek et al conducted a crossover, randomized controlled trial of 20 patients, where randomization was performed in 2 groups of 10 patients.38 They either received MPFF 500 mg twice a day (treatment group) for 6 months or vitamin pills as placebo (control group) twice a day over the same period. Treatments were then crossed over for an additional 6 months. Patients were asked to assess their chronic pelvic pain monthly using a 6-point scale (0 for no pain to 6 for intense pain). There was an improvement in pelvic pain scores starting at 2 months in the treatment group compared with the control group, which was significant (P<0.05) at the time of the crossover (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Improvement in pelvic pain scores after a 6-month

treatment with MPFF.

Group A. Started with MPFF 500 mg and were then switched to

vitamins for placebo effect for 6 to 12 months. Group B. Second

arm of the study group received vitamins for 6 months and were

then switched to MPFF 500 mg for 6 to 12 months.

Abbreviations: MPFF, micronized purified flavonoid fraction.

Modified from reference 38: Simsek et al. Clin Exp Obstet

Gynecol. 2007;34:96-98.

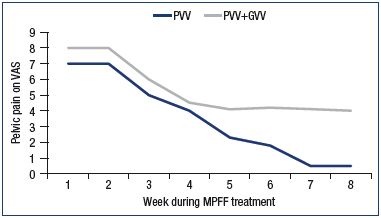

Figure 2. Assessment of pelvic venous pain on a 10-cm visual

analog scale.

Patients with pelvic vein dilation in isolated PVV or in PVV + GVV

were treated with MPFF for 8 weeks.

Abbreviations: GVV, gonadal varicose veins; MPFF, micronized

purified flavonoid fraction; PVV, pelvic varicose veins; VAS, visual

analog scale.

Modified from reference 39: Gavrilov et al. Angiol Sosud Khir.

2012;18(1):71-75.

This study showed a statistically significant improvement in pelvic pain scores in both groups, without any side effects.

In a trial by Gavrilov et al, 85 women suffering from chronic pelvic pain associated with pelvic varicose veins in isolation (PVV group) or with both pelvic and gonadal varices (PVV+GVV group), MPFF at 1000 mg a day for 8 weeks was more efficient in PVV patients with isolated dilatation of uterine and parametrial veins than in the PVV+GVV group.39 A continuous decrease in pain was reported by the PVV patients up to week 8 of treatment, and symptoms completely disappeared at 14 weeks. The clinical effect persisted for a long time (6 to 9 months) with a stabilization of the disease course (Figure 2). In addition, pelvic venous congestion declined, as shown by emission computed tomography, reflecting a restoration of the pelvic circulation in this group (Figure 3). There was no additional pain reduction in the PVV+GVV group.

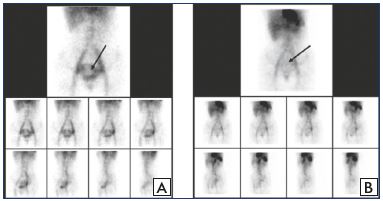

Figure 3. ECT assessment of pelvic veins before and after MPFF

treatment.

ECT of the pelvic veins at baseline (Panel A) and after an 8-week

MPFF treatment (Panel B) in a patient with pelvic vein dilation

in isolated PVV. Deposit of labeled erythrocytes in the uterine

venous plexus is indicated by the arrows.

Abbreviations: ECT, emission computed tomography; MPFF,

micronized purified flavonoid fraction; PVV, pelvic varicose veins.

From reference 39: Gavrilov et al. Angiol Sosud Khir.

2012;18(1):71-75.

Based on these two studies on women with PCS, initial pharmacologic enhancement of venous tone with venoactive drugs, such as MPFF, may restore pelvic circulation and relieve pelvic symptoms, such as pain and heaviness, in the long-term.

Long-term effectiveness of medical treatments

The above-mentioned studies have shown that medical management of PCS can prove to be beneficial for women; however, there is insufficient evidence regarding their longterm effectiveness in controlling their debilitating symptoms. Specifically, GnRH agonists may be used for 6 months without add-back hormone replacement therapy or up to 2 years with add-back hormone replacement therapy to reduce the risk of osteoporosis. Therefore, the use of progestins should be further evaluated as a long-term treatment option for PCS, taking into account that bone density is slightly reduced during usage. The reduction in bone density appears to be reversible and it is probably of minor clinical significance in women in their second and third decade; however, there are some concerns about the reversibility of bone mineral density reduction in women in their early and later reproductive years.

Long-term benefits of MPA and/or GnRH agonists have been demonstrated previously.20,24,33,35 In fact, long-term therapy with progestins appears to be more favorable than with GnRH analogs. The limitations of GnRH agonists were side effects, costs, and the inability to use them for a long-term course due to the risk of menopausal symptoms and osteoporosis. Of the progestins cited above, Implanon seems to offer good results in pelvic pain alleviation with tolerable side effects in selected patients with symptomatic and pure PCS. Overall, nearly 80% of the women were satisfied after 3 months of treatment. Implanon probably is an option for long-term medical treatment and it should be more extensively evaluated for this indication in comparison with other medical treatments.

Patients who are refractory to medical therapy may then be considered for ligation, embolization, or sclerotherapy of the ovarian veins. However, randomized clinical trials have not yet distinguished or identified a top choice between existing invasive techniques.

A look into the future

The conclusion drawn by the Chronic Pelvic Pain Working Group in 2005 could be applied to the medical treatment of PCS in the future, particularly to women with PCS who are complaining of chronic pelvic pain:

…in the future, a woman with chronic pelvic pain will be recognized as having a condition that requires rehabilitation and not solely acute care management. She will be managed by a team of individuals who are aware of the principles of multidisciplinary care, including a physiotherapist, a psychologist, a primary care physician, and a gynecologist.

Such an approach will be funded by the local hospital or regional health authority on the basis of its effectiveness and cost efficiency. Emphasis will be placed on achieving higher function in life with some pain rather than cure. The management of directed therapy will be based on treatments that have been subjected to clinical trial. There will be a permanent record of the findings at any previous laparoscopy that can be shared and compared over time. Health personnel involved in the patient’s management will have been trained in the specific areas of this disease management.32

Finally, a multidisciplinary approach to diagnosis and care is currently recommended.32

REFERENCES

1. Eklof B, Perrin M, Delis KT, Rutherford RB, Gloviczki P. Updated terminology of chronic venous disorders: the VEINTERM transatlantic interdisciplinary consensus document. J Vasc Surg. 2009;49:498-501.

2. Koo S, Fan CM. Pelvic congestion syndrome and pelvic varicosities. Tech Vasc Interv Radiol

3. Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. The initial management of chronic pelvic pain. Green-top Guideline No. 41, 2012. https://www. rcog.org.uk/globalassets / documents/ guidelines/gtg_41.pdf. Published May 2012. Accessed July 20, 2016.

4. Park SJ, Lim JV, Ko YT, Lee DH, Yoon Y, Oh JH, et al. Diagnosis of pelvic congestion syndrome using transabdominal and transvaginal sonography. Am J Roentgenol

5. Belenky A, Bartal G, Atar E, Bachar GN. Ovarian varices in healthy female kidney donors: incidence, morbidity, and clinical outcome. AJR Am J Roentgenol

6. Monedero JL, Ezpeleta SZ, Perrin M. Pelvic congestion syndrome can be treated operatively with good longterm results. Phlebology

7. Hodson TJ, Reed MW, Peck RJ, Hemingway AP. Case report: the ultrasound and Doppler appearances of pelvic varices. Clin Radiol

8. Giacchetto C, Cotroneo GB, Marincolo F, Cammisuli F, Caruso G, Catizone F. Ovarian varicocele: ultrasonic and phlebographic evaluation. J Clin Ultrasound

9. Kurt A, Gültaply NZ, Ýpek A, Gümüp M, Yazycyoplu KR, Dilmen G, Tap Y. The relation between pelvic varicose veins, chronic pelvic pain, and lower extremity venous insufficiency in women. Phlebolymphology

10. Rozenblit AM, Ricci ZJ, Tuvia J, Amis ES Jr. Incompetent and dilated ovarian veins: a common CT finding in asymptomatic parous women. Am J Roentgenol

11. Desimpelaere JH, Seynaeve PC, Hagers YM, Appel BJ, Mortelmans LL. Pelvic congestion syndrome: demonstration and diagnosis by helical CT. Abdom Imaging

12. Campbell D, Halligan S, Bartam CI, Rogers V, Hollings N, Kingston K et al. Transvaginal power Doppler ultrasound in pelvic congestion. Acta Radiol

13. Ignacio EA, Dua R, Sarin S, Harper AS, Yim D, Mathur V, et al. Pelvic congestion syndrome: diagnosis and treatment. Semin Intervent Radiol

14. Ahangari A. Prevalence of chronic pelvic pain among women: an updated review. Pain Physician

15. Reiter RC. A profile of women with chronic pelvic pain. Clin Obstet Gynecol

16. Meneses LQ, Uribe S, Tejos C, Andia ME, Fava M, Irarrazaval P. Using magnetic resonance phase-contrast velocity mapping for diagnosing pelvic congestion syndrome. Phlebology

17. Nicholson T, Basile A. Pelvic congestion syndrome, who should we treat and how? Tech Vasc Interv Radiol

18. Topolanski-Sierra R. Pelvic phlebography. Am J Obstet Gynecol

19. Sator-Katzenschlager SM, Scharbert G, Kress HG, Frickey N, Ellend A, Gleiss A, et al. Chronic pelvic pain treated with gabapentin and amitriptyline: a randomized controlled pilot study. Wien Klin Wochenschr

20. Reginald PW, Beard RW, Kooner JS, Mathias CJ, Samarage SU, Sutherland IA et al. Intravenous dihydroergotamine to relieve pelvic congestion with pain in young women. Lancet

21. Barthel W. Venous tonus-modifying effect, pharmacokinetics and undesired effects of dihydroergotamine. [Article in German]. Z Gesamte Inn Med

22. Beard RW, Highman JH, Pearce S, Reginald PW. Diagnosis of pelvic varicosities in women with chronic pelvic pain. Lancet

23. Schindler AE, Campagnoli C, Druckmann R, Mathias CJ, Samarage SU, Sutherland IA et al. Classification and pharmacology of progestins. Maturitas

24. Farquhar CM, Rogers V, Franks S, Pearce S, Wadsworth J, Beard RW. A randomized controlled trial of medroxyprogesterone acetate and psychotherapy for the treatment of pelvic congestion. Br J Obstet Gynaecol

25. Reginald PW, Adams J, Franks S, Wadsworth J, Beard RW. Medroxyprogesterone acetate in the treatment of pelvic pain due to venous congestion. Br J Obstet Gynaecol

26. Brown J, Kives S, Akhtar M. Progestagens and anti-progestagens for pain associated with endometriosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev

27. Crosignani PG, Luciano A, Ray A, Bergqvist A. Subcutaneous depot medroxyprogesterone acetate versus leuprolide acetate in the treatment of endometriosis-associated pain. Hum Reprod

28. Astra Zeneca official Zoladex site. https://www.zoladex.co.uk/home.html. Accessed July 20, 2016.

29. Soysal ME, Soysal S, Vicdan K, Ozer S. A randomized controlled trial of goserelin and medroxyprogesterone acetate in the treatment of pelvic congestion. Hum Reprod

30. Lauersen NH, Wilson KH, Birnbaum S. Danazol: an antigonadotropic agent in the treatment of pelvic endometriosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol

31. Telimaa S, Puolakka J, Rönnberg L, Kauppila A. Placebo-controlled comparison of danazol and high-dose medroxyprogesterone acetate in the treatment of endometriosis. Gynecol Endocrinol

32. Jarrell JF, Vilos GA, Allaire C; Chronic Pelvic Pain Working Group; SOGC. Consensus guidelines for the management of chronic pelvic pain. J Obstet Gynaecol Can

33. Wagner MS, Arias RD, Nucatola DL. The combined etonogestrel/ethinyl estradiol contraceptive vaginal ring. Expert Opin Pharmacother

34. Power J, French R, Cowan F. Subdermal implantable contraceptives versus other forms of reversible contraceptives or other implants as effective methods of preventing pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev

35. Gezginc K, Balci O, Karatayli R, Colak- Oglu MC. Contraceptive efficacy and side effects of Implanon. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care

36. Stones RW, Mountfield J. Interventions for treating chronic pelvic pain in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev

37. Shokeir T, Amr M, Abdelshaheed M. The efficacy of Implanon for the treatment of chronic pelvic pain associated with pelvic congestion: 1-year randomized controlled pilot study. Arch Gynecol Obstet

38. Simsek M, Burak F, Taskin O. Effects of micronized purified flavonoid fraction on pelvic pain in women with laparoscopically diagnosed pelvic congestion syndrome: a randomized crossover trial. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol

39. Gavrilov SG, Karalkin AV, Moskalenko EP, Beliaeva ES, Ianina AM, Kirienko AI. Micronized purified flavonoid fraction in treatment of pelvic varicose veins [in Russian]. Angiol Sosud Khir

40. Lyseng-Williamson KA, Perry CM. Micronised purified flavonoid fraction: a review of its use in chronic venous insufficiency, venous ulcers and haemorrhoids. Drugs

41. Hnátek L. Therapeutic potential of micronized purified flavonoid fraction (MPFF) of diosmin and hesperidin in treatment chronic venous disorder [in Czech]. Vnitr Lek