Patients seeking treatment for chronic venous disorders: Russian results from the VEIN Act program

chronic venous disorders:

Russian results from the VEIN Act

program

Alexander I. KIRIENKO,2

Anatoly A. LARIONOV,1

Alexander I. CHERNOOKOV3

2 N.I. Pirogov ’s Russian National Research

Medical University

3 I.M. Sechenov First Moscow State

Medical University

Moscow, Russian Federation

Abstract

Objective: The Russian VEIN Act program (chronic VEnous dIsorders maNagement and EvaluAtion of Chronic venous disease treatment effecTiveness) was an observational, prospective survey, carried out under the auspices of the European Venous Forum that was designed to assess compliance with nonsurgical treatments (lifestyle advice, venoactive drugs, and compression therapy) for chronic venous disorders (CVD) in the framework of ordinary specialized consultations.

Methods: Adult patients complaining of venous pain associated with signs of CVD underwent a leg examination. Following confirmation of a CVD diagnosis, a case report form was completed listing the patient’s clinical presentation and history, reported symptoms, and prescribed nonsurgical treatments. Patients were advised to return for a follow-up visit at which compliance with prescribed treatments was assessed.

Results: A total of 1607 patients were enrolled by 82 phlebologists in Russia. The time gap between the first visit (V0) and the follow-up visit (V1) was 3 months. Patients were predominantly female (80%), aged 45.71±14 years, and with a mean body mass index (BMI) of 26.02±5.02 kg/m2. A total of 92% patients reported that they had experienced venous symptoms over the last 4 weeks. More women than men complained of venous symptoms and the symptom prevalence increased with age in women (not in men), but sex did not influence the intensity of the symptoms. Symptom intensity increased with higher BMI and Clinical, Etiological, Anatomical, and Pathological (CEAP) class in both sexes.

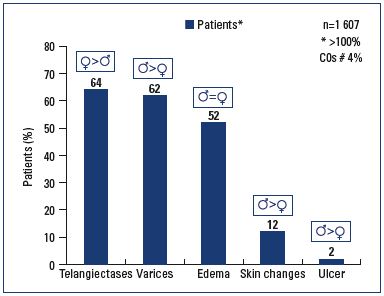

Patients reported suffering the following CVD signs: telangiectases (65%), varicose veins (63%), edema (52%), skin changes (11%), and/or venous ulcers (2%). Edema was equally reported in men and women, but more women than men complained of telangiectases (72% vs 33%; P<0.0001); while more men than women presented with varicose veins (82% vs 57%; P<0.0001), skin changes(13% vs 8%; P<0.0001), and venous ulcers (4% vs 1.5%; P<0.0001). All signs increased with age in either sex, except telangiectases, which was more often reported by younger women (P<0.0001).

Most patients (78%) were receiving a treatment combining lifestyle advice, venoactive drugs, and compression therapy. Only a few were receiving a single treatment (<3%). The type and combination of treatment did not vary according to patient profiles, except for CEAP.

At V1, patients who were prescribed a venoactive drug reported that they had correctly complied with the dosage in 98% of cases, but this dropped to 72% when the duration of treatment was longer than 9 weeks. Compliance with lifestyle advice was reported by 91% of patients. Only 75% of patients with a prescription for compression therapy attended the V1 appointment wearing the compression hosiery correctly, and 44% reported that they had worn the hosiery as prescribed. The majority did not follow the prescription and wore the hosiery either most days (30%), intermittently (19%), or not at all (6%). The reasons for not wearing the hosiery were: “too difficult to put on” in 47%; “not comfortable” in 32%; “too warm” in 22%; “itches” in 18%; and “not aesthetic” in 12%. Age group, sex, BMI, symptom intensity, and CEAP classification were variables that influenced compliance to treatment.

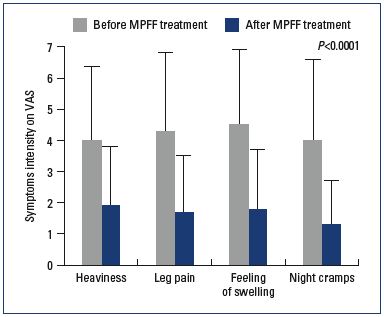

Of the 89 followed-up respondents who received micronized purified flavonoid fraction (MPFF) in isolation, symptom disappearance was seen in 5.3% of those with leg heaviness, 29.8% with pain, 32.5% with a feeling of swelling, and 20.6% with cramps. This was significant for pain (P=0.0017). The intensity of symptoms was significantly decreased on the VAS: (P<0.0001) -2.1±2.2 cm for leg heaviness, -2.6±2.2 cm for pain, -2.6±1.9 cm for a feeling of swelling, and -2.6±2.1 cm for cramps. The frequency and time (after prolonged standing or during the night) at which symptoms were felt were significantly reduced after MPFF treatment.

Conclusion: The VEIN Act Program reflects the profile of patients with CVD consulting phlebologists in Russia. CVD is a chronic and progressive disease and educational efforts are needed to raise awareness among Russian physicians, patients, and the scientific community about the necessity for earlier diagnosis, particularly in men, and for better treatment compliance.

Introduction

Chronic venous disorders (CVD) of the lower extremities are characterized by a wide range of symptoms and signs, resulting from abnormalities in the venous system.1,2 All forms of CVD are related to venous hypertension, which is caused by reflux through faulty valves.1,2 Cases of CVD can range from early to severe. Early symptoms include heavy legs, leg pain, a sensation of swelling, and pins and needles in the legs, and can progress to signs including varicose veins, edema and leg ulcers, the most chronic manifestation.

CVD is a common condition that has a significant impact on both the individuals affected and the health care system. It is estimated that 30% to 35% of the general population can be classed as C0 and C1 of the Clinical, Etiological, Anatomical, and Pathological (CEAP) classification system.3,4 This includes the 20% of the adult population with venous symptoms, but no visible or palpable signs of venous disease (C0s) and those with telangiectases or reticular veins (C1).5 In Europe, more severe stages of the disease, such as skin changes and active ulceration, may affect 5% to 15% of the population.4,5 The quality of life (QOL) assessment is directly associated with the severity of venous disease.6 Patients who have or have had venous ulcers report a QOL similar to patients suffering with congestive heart failure.7 The initial management of CVD involves nonoperative measures to reduce symptoms and prevent development of secondary complications and progression of the disease. Nonoperative treatment includes lifestyle advice, pharmacological treatment using venoactive drugs (VADs), and compression stockings.8 The specific treatment prescribed is based on the severity of disease with CEAP classes C4 to C6 and often requires invasive treatment. A referral to a vascular specialist should be made for patients with CEAP classes C4 to C6 (and probably also for CEAP class C3 with extensive edema).8 A healthy lifestyle, including maintaining an ideal body weight or weight reduction if overweight, may improve the manifestations of CVD as obesity is a well-established risk factor for its development.9

Some patients, however, will not comply with the prescribed treatment for various reasons. The problem of noncompliance is well known to venous specialists and how to improve it has been the subject of much debate.10,11 Available data describing the extent of noncompliance in CVD have been limited to a series of patients with venous ulceration using compression therapy (CT).12,13 The degreeof noncompliance to other noninvasive treatments and in other symptom subsets remains undefined.

Aims

The VEIN Act program (chronic VEnous dIsorders maNagement and evaluAtion of Chronic venous disease treatment effecTiveness) was an international educational effort aimed at helping physicians, patients, and the scientific community assess compliance with nonsurgical treatments for CVD.

The program also aims to frame the profile of patients seeking medical care for CVD and assess the effects of nonsurgical treatments in patients with symptomatic CVD, in terms of symptom improvement, amelioration of daily activity, and patient satisfaction.

Materials and methods

Design

The VEIN Act program is a prospective, multicenter, observational survey carried out under the auspices of the European Venous Forum and supported by an unrestricted grant from the Servier Research Group. It was performed in the framework of ordinary consultations.

Patients

At first consultation (V0), patients complaining of pain in the lower limbs and consulting for any clinical presentation related to CVD were recruited. The suitability of the patients for involvement in the program was determined using the following criteria: male or female over 18 years old (not having ongoing treatment for CVD); informed of their involvement in the program, their right to refuse to participate fully or partly, and providing consent; not consulting for an emergency or for an acute episode of an ongoing event; and free of concomitant diseases that might interfere with venous treatment.

If these criteria were met, the patients were asked about venous signs and symptoms and then underwent a leg examination (if this was routine practice). If the patient presented with at least one venous symptom or venous sign or both, a case report form was completed with the following information: patient’s clinical presentation and history, presence of CVD signs and/or symptoms, and the nonsurgical treatments prescribed, listing all treatment characteristics. Patients were advised to return for a routine follow-up visit (V1).

The V1 follow-up consultation was scheduled, if possible, at the end of the prescription duration. At this visit, compliance with and the effect of treatment were assessed, together with patient satisfaction. Reasons for noncompliance, if any, were also sought.

Characterization of chronic venous disorders symptoms and signs

Symptoms were confirmed as being related to CVD, if one of the four following symptoms was present (heavy legs, pain in the legs, a sensation of swelling, and cramps) and if there was an increase in severity in two of the following circumstances: “after prolonged standing,” and/or “at the end of the day,” and/or “during the night.” CVD signs were described according to the Clinical, Etiological, Anatomical, Pathophysiological (CEAP) classification.14

Assessment of chronic venous disorder symptoms

The visual analog scale (VAS), which consists of a straight horizontal line 100 mm in length, is applicable to all patients regardless of language.15 “No symptoms” was marked on the left side of the scale and “Unbearable symptoms” on the right side. Patients were requested to indicate the intensity of their symptoms by using the VAS and to circle on a 5-point verbal scale the daily frequency of the symptoms as: “throughout the day and night,” “regularly,” “occasionally,” “rarely,” or “never.”

Description of chronic venous disorders signs

Patients were classified by physicians according to the clinical CEAP stage (the highest class was retained for the patient’s classification) as follows: C0s, no visible signs; C1, telangiectases, reticular veins; C2, varicose veins; C3, edema; C4a, skin changes with pigmentation or eczema; C4b, skin changes with lipodermatosclerosis or atrophie blanche; C5, healed ulcer; C6, active ulcer.

Results

Enrollment in the survey

The Russian VEIN Act Program was performed between April 2013 and June 2014 by 82 venous specialists. A total of 1607 patients were enrolled at the first visit V0, and 1590 patients returned for a follow-up visit at V1. The mean time between visits V0 and V1 was 83 days, ie, around 3 months, and no statistical difference was observed between men and women regarding the time interval between visits (P=0.93).

Patients’ profile at V0

Participants in the Russian VEIN Act Program were predominantly female (79.8%), had a mean age of 45.7±14 years, and a mean a body mass index (BMI) of 26.02±5.02 kg/m2.

Symptoms and signs

Most patients reported that they had had symptoms over the last 4 weeks. The symptoms, in order of frequency, were: heaviness (91.8%); leg pain (70.2%); sensation of swelling (69.7%); and cramps (45.7%). Each patient complained of a mean of 2.8±1 symptoms with an intensity on the VAS ≥4 cm: heaviness (5.2±2 cm); leg pain (4.8±2.2 cm); sensation of swelling (4.9±2.3 cm); and cramps (4.0±.5 cm). Symptom intensification occurred mostly at the end of the day for 89.1% of consulting patients and after prolonged standing for 59.5%.

On a daily basis, patients reported that their symptoms were present “regularly” and “throughout the day and night” in almost 60% of cases, and “occasionally,” “rarely,” or “never” in 40% of cases.

Women complained of their symptoms more often than men (91% vs 80%; P<0.0001), but symptom prevalence increased with age in men, but not in women. Symptom intensity increased with BMI and with increasing CEAP class in both sexes. The daily frequency of symptoms increased with age in both sexes.

Self-reported signs of CVD included: telangiectases (65%), and/or varicose veins (63%), edema (52%), skin changes (11%), venous ulcer (2%) (Figure 1). Swollen legs and edema were reported in an equal number of men and women (52%; P=NS). More women than men consulted with telangiectases (72% vs 33%; P<0.0001), while more men than women consulted with varicose veins (82% vs 57%; P<0.0001), skin changes (13% vs 8%; P<0.0001), and/or active or healed venous ulcers (4% vs 1.5%; P<0.0001). Younger women were more likely to consult for telangiectases than older women (64% of women ≤50 years vs 36% of women ≥51 years; P=0.0005), but this was not statistically significant in men. The presence of varicose veins caused younger men to consult more (56% of men ≤50 years vs 44% of men ≥51 years; P=0.0014), while this behavior was not related to age in women. The proportion of patients reporting clinical signs significantly increased with older age in both sexes (P<0.005).

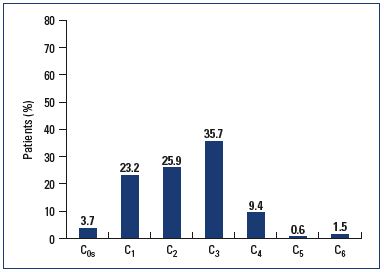

In terms of CEAP classification, physicians found that 3.7% of patients presented with no signs, but only symptoms (C0s) (Figure 2). Due to the fact that only the higher CEAP class was considered and that doctors could tick only one box (while patients could report several signs and tick several boxes), the prevalence of physician-reported clinical signs was lower than that of patient self-reported signs, as follows:

• 23% of the survey population consulting for leg problems was classified as C1. Women consulted more often for telangiectases than men (5% of men and 28% of women; P<0.0001)

• 26% (35% of men and 24% of women; P<0.0001) were C2

• 36% were C3 with no difference between sexes (P=NS)

• 11.5% were C4 to C6 with a predominance of men over women (17.7% vs 9.8%; P<0.0001).

Whatever the method used for reporting signs, the sex difference followed similar trends.

Treatment of chronic venous disorders

Almost 40% of patients had already consulted a doctor, and 31% had previously been treated for their leg problems. These figures significantly increased with older age, increasing BMI, symptom intensity, and CEAP class, whatever the patients’ sex (P<0.0001). Nearly all patients (99.7%) who consulted for leg problems at V0 were prescribed a treatment, whichever CEAP clinical class they were assigned, including C0s (P=NS). Nonsurgical treatment was prescribed in 66% of patients, and nonoperative plus sclerosing treatment was performed in 33.6% of patients. Only 0.4% underwent a single surgical procedure. Nonoperative treatment consisted of a combination of lifestyle advice, VADs and CT in 78% of cases, VADs plus CT in 10% of cases, and VADs + lifestyle advice in 5% of cases. A few patients received a single nonoperative treatment (<3%). The severity of disease according to the CEAP classification significantly influenced the type of prescribed treatment (P=0.0004), whereas sex, age, and BMI did not. While all C0s patients received a nonoperative treatment alone, patients in other CEAP classes were often prescribed a dual nonoperative plus sclerosing treatment, and C4 to C6 patients could benefit from additional painkilling drugs.

At V0, the majority of patients (97%) were prescribed VADs in association with lifestyle advice and/or CT, or in isolation (2%). For 57% of patients, drugs were prescribed for more than 9 weeks, while the remaining 43% received a shorter treatment (≤8 weeks) at a dose of 2.0±.2 tablets a day for any drug brand.

CT was prescribed to 92% of the survey population in association with other treatments. Stockings were preferred to bandages (98.5% vs 1.5%), at thigh level (84%) rather than below the knee (16%), and were prescribed for 8 weeks or less in 20% of patients and 9 weeks or more in most of patients (80%). It should be noted that for most patients, doctors prescribed CT for a longer duration than VADs. The majority of consulting patients received moderate strength CT (63%), 34% a light- or mild-strength CT, and 3% a high-strength CT. A single device was prescribed in 62% of patients, two devices in 36%, and more than two devices in 2%.

Assessment of compliance to treatments at V1

Lifestyle advice

Lifestyle advice was associated with either VADs, compression therapy, or both in 88% of consulting patients, and was rarely prescribed alone (1%). Among the patients who received lifestyle advice, 91% reported they had correctly followed the prescription, including choosing the right exercise (84%), aiding blood return by leg elevation (81%), moving legs in all circumstances (80%), wearing shoes with suitable heels (70%), avoiding warmth (59%), losing weight (52%), and massaging legs as often as possible (37%). Reasons for noncompliance were difficulty in adopting these measures daily (58%) and lack of time (38%).

Venoactive drugs

Among the patients who were prescribed VADs, 98% reported they had respected the dosage and 97% reported that they had purchased the prescribed drug brand name. The few who did not buy the prescribed brand stated that this was because the pharmacist had changed it for another brand (35%) or either the brand was not always available at the purchase point (16%). At V0, most patients were prescribed long-term treatment (≥9 weeks). At V1, 87% of the patients had complied with the prescription duration if it was ≤8 weeks and 72% if it was ≥9 weeks. The reasons for not respecting the treatment duration were described as: “forgot to take it” (27%), “took other pills” (14%), and “lack of efficacy” (13%). Younger patients (≤50 years) were more likely to forget to take their VAD, while older patients (>65 years) were more likely to complain about a lack of treatment efficacy.

Sex, BMI, CEAP class, and symptom intensity did not affect compliance with VADs or to lifestyle advice.

Compression therapy

Among the patients prescribed CT, only 75% attended the V1 appointment wearing the compression hosiery correctly. Almost half the patients (45%) reported using the stockings on a daily basis, 30% used them most days, and 19% used them less often. The remaining 6% did not use the stockings at all or abandoned them after a trial period.

The reasons for not wearing the compression hosiery included: “too difficult to put on” in 47% of patients; “not comfortable” in 32%; “too warm” in 22%; “itches” in 18%; “not aesthetic” in 12% and “ineffective” (2%). For the remainning 26%, no specific reason was given. Only ‘too difficult to put on’ and ‘unattractive’ were significantly dependent on CEAP class: patients in severe stages (C5,6) more often felt that CT was ‘too difficult to put on’ (73% in C5,6 vs 47% in all CT patients, P=0.0028), and those in C1 found it particularly ‘unattractive’ (22% in C1 vs 12% in all CT patients, P=0.023). A number of variables influenced the compliance to CT.

Women were more likely to find CT unattractive compared with men (14% vs 6%; P=0.04), while men were more likely to find the hosiery too warm (30% vs 20%; P=0.05). Age also had an impact on whether CT was worn: younger patients finding it unattractive (72% in patients ≤50 years vs 18% in those ≥51 years; P=0.008) or too warm (67% in patients ≤years vs 33% in those ≥51 years; P=0.02). Older patients were more likely to find CT too difficult to put on (53% in those ≥51 years vs 47% in those ≤50 years; P=0.0004). CEAP classification also influenced wearing of CT. Of the 1431 patients who responded to the question on compliance with CT, 636 (44%) reported they had worn the stockings “as prescribed”: 17% in C0s, 37% in C1, 42% in C2, 50% in C3, 53% in C4, and 38% in C5-C6 (sample size of C5-6 was small, only 6 patients). The higher the CEAP class (from C0s to C4), the better the compliance with the CT prescription. Only 5% had not worn stockings at all, mostly in the C0s and C5-6 classes.

The strength of the purchased CT was described as “moderate” or “mild” in 95% of CT patients: 88% in C0s, 96% in C1, 98% in C2, 96% in C3, 83% in C4, and 82% in C5-6 patients. Strong and very strong compression strengths were bought mainly by C4 and C5-6 patients (16% in C4 and 18% in C5-6 vs 3% in all CT patients, P<0.0001).

Assessment of treatment efficacy

Efficacy of combined treatment

A total of 1368 patients with combined treatment were followed-up at V1. Symptom disappearance was observed in 6.3% of patients with leg heaviness, 33.6% with pain, 28.8% with a feeling of swelling, and 43.8% with cramps (P<0.0001). The intensity of symptoms on the VAS decreased by at least (-2.3±2.5 cm). The frequency at which symptoms were felt was significantly reduced from “Occasionally,” “Regularly”, and “Throughout the day and night” to “Never” and “Rarely” in 57% of patients; (P<0.0001). Among the patients who felt symptoms more intensively during the night, 75% no longer complained of symptom intensification at this time. In addition, 39% and 18% no longer complained of symptoms after prolonged standing, or at the end of day, respectively.

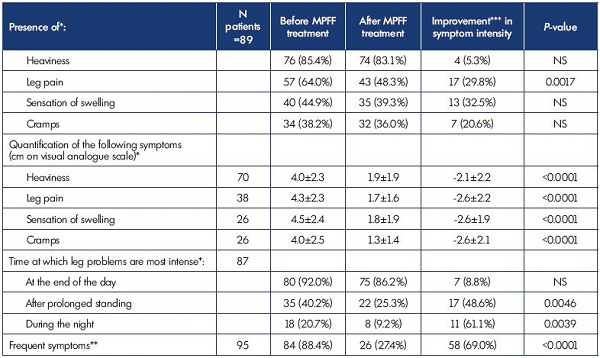

Table I. Symptom improvement after treatment with MPFF in terms of symptom disappearance and decreased symptom intensity

and frequency.

* Total of the items can exceed the total number of patients as patients can tick several boxes for this question

** Frequent = “Occasionally,” “Regularly,” and “Throughout the day and night” frequencies; Nonfrequent = “Never” and “Rarely” frequencies

*** Improvement is defined as a presence/frequency at V0 and an absence/no frequency at V1

Efficacy of micronized purified flavonoid fraction on venous symptoms

A total of 89 respondents who received micronized purified flavonoid fraction (MPFF) treatment without any other combined treatment were followed-up at V1. Symptom disappearance was seen in 5.3% of those with leg heaviness, 29.8% with pain, 32.5% with a feeling of swelling, and 20.6% with cramps (Table I). Due to the low sample size, this was significant for pain only (P=0.0017). The intensity of symptoms was significantly decreased on the VAS: -2.1±2.2 cm for leg heaviness, -2.6±2.2 cm for pain, -2.6±1.9 cm for a feeling of swelling, and -2.6±2.1 cm for cramps; P<0.0001 (Figure 3). The frequency at which symptoms were felt was significantly reduced from “Occasionally,” “Regulary”, and “Throughout the day and night” to a frequency of “Never” and “Rarely” in 69% of patients P<0.0001. Among the patients who felt symptoms more intensively during the night, 61% no longer complained of symptom intensification at this time, 48% no longer complained after prolonged standing, and 9% no longer complained of symptom intensification at the end of day (Table I).

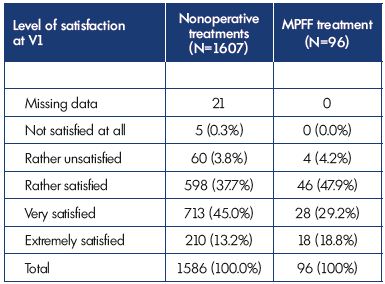

Patients’ satisfaction with nonoperative treatment

Patients were rather, very, or extremely satisfied in 96% of cases with either combined nonoperative treatment or MPFF treatment alone (Table II). The degree of patient satisfaction was not dependent on any variables (sex, age, BMI, CEAP class, or symptom intensity).

Figure 3. Improvement in venous symptoms with MPFF.

*Abbreviations: MPFF, micronized purified flavonoid fraction; VAS, 10 cmvisual

analog scale.

Discussion

The VEIN Act Program provides a snapshot of individuals suffering from venous leg problems and seeking medical help in the framework of ordinary consultations in Russia. It revealed that women are more likely to consult for their leg problems than men. In addition, more women than men consulted with telangiectases, particularly at a younger age (≤50 years), whereas more men than women consulted with varicose veins, skin changes, and active or healed venous ulcers, suggesting that men are more hesitant to consult earlier in the disease process. Only 3% of consulting patients had symptoms without visible signs (C0s), whatever their sex. In contrast, the Vein Consult Program revealed that almost 20% of the Russian adult population could be assigned to the C0s class.5 At this stage, patients are not aware that symptoms could hide an underlying venous disease.

Whatever the method used for reporting signs in consulting patients (patient self-reported signs or physician-reported CEAP), the trends were similar, particularly in terms of the sex differences. However, the use of the simplified CEAP clinical classification for reporting signs does not entirely reflect reality and tends to underestimate the early signs of disease (eg, telangiectases, varices).

Almost all patients (99.7%) consulting phlebologists for their leg problems received nonoperative treatments, consisting of lifestyle advice, VADs, or CT (mostly in combination), or with sclerosing agents. Additional painkilling drugs were reserved for C4 to C6 patients.

Phlebologists tended to recommend advice that was easy to follow (leg elevation, leg movement, shoes with suitable heels), while weight loss and leg massages were less frequently proposed, providing a potential explanation for the high rate of compliance with lifestyle advice (91%) in this study. Patients prescribed VADs satisfactorily complied with the prescription duration if it was ≤8 weeks (87%), but less so if the treatment duration was ≥9 weeks (72%).

In the majority of patients prescribed CT (95%), the strength of compression purchased was “moderate” or “mild.” Most patients were prescribed CT for a duration of ≥9 weeks, but less than half of the patients (44%) reported using the stockings as prescribed (ie, on a daily basis), 30% used them most days, and 19% used them intermittently. Noncompliance was due to physical reasons related to the stockings (“too difficult to put on,” “uncomfortable,” “too warm”) in more than 22% of Russian patients. Another 26% of the patients in this series could not state a specific physical reason for noncompliance. As stated by Raju,12,16 “these patients are unwilling to tolerate the intangible sense of restriction imposed by daily stocking wear. There is probably considerable overlap between these two groups. In either case, the central factor behind noncompliance appears to be the pressure exerted by the compression stockings themselves–precisely the property that underpins efficacy in controlling symptoms, suggesting that many patients consider compression stockings a quality of life issue.”

In the current study, nonoperative treatment, combined or in isolation (MPFF alone), proved efficient in terms of alleviating symptoms and reducing symptom intensity and daily frequency. Patients were relieved from heaviness, leg pain, feeling of swelling, and cramps. Relief from leg pain was significant with MPFF treatment (P=0.0017). There was a highly significant decrease in the intensity of all symptoms (at least 2 cm on the VAS) with combined nonoperative treatment or with MPFF alone (P<0.0001). The daily frequency at which symptoms were felt was also significantly reduced (P<0.0001) with combined nonoperative treatment or with MPFF alone.

Conclusion

The VEIN Act program reflects the profile of Russian patients with CVD consulting a phlebologist. It shows that educational efforts are needed to raise awareness among physicians, patients, and the scientific community about the necessity of earlier diagnosis, particularly among men. It also highlights the need for better treatment compliance, as CVD is a chronic and progressive disease. Nonoperative treatments, such as MPFF, proved easy for patients to comply with and efficient in terms of symptom relief and reduction in symptom intensity and daily frequency; thereby, improving patients’ daily life.

1. Nicolaides A, Kakkos S, Eklof B, at al. Management of chronic venous disorders of the lower limbs. Guidelines according to scientific evidence. Int Angiol. 2014;33:111-260.

2. Bergan JJ, Schmid-Schönbein GW, Coleridge Smith PD, et al. Chronic venous disease. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:488-498.

3. Langer RD, Ho E, Denenberg JO, et al. Relationships between symptoms and venous diease. The San Diego Population Study. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:1420- 1424.

4. Rabe E, Pannier F. What have we learned from the Bonn Vein Study? Phlebolymphology. 2006;13:188-194.

5. Rabe E, Guex JJ, Puskas A, VCP coordinators. Epidemiology of chronic venous disorders in geographically diverse populations: results from the Vein Consult Program. Int Angiol. 2012;31:105-115.

6. K aplan RM, Criqui MH, Denenberg JO, et al. Quality of life in patients with chronic venous disease: San Diego population study. J Vasc Surg. 2003;37:1047-1053.

7. Andreozzi GM, Cordova RM, Scomparin A, et al. Quality of life in chronic venous insufficiency. An Italian pilot study of the Triveneto Region. Int Angiol. 2005;24:272-277.

8. Eberhardt RT, Raffetto JD. Chronic venous insufficiency. Circulation. 2014;130:333- 346.

9. Van Rij AM, De Alwis CS, Jiang P, et al. Obesity and impaired venous function. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2008;35:739- 744.

10. Jull AB, Mitchell N, Arroll J, et al. Factors influencing concordance with compression stockings after venous leg ulcer healing. J Wound Care. 2004;13:90-92.

11. McMullin GM. Improving the treatment of leg ulcers. Med J Aust. 2001;175:375- 378.

12. Raju S, Hollis K, Neglen P. Use of compression stockings in chronic venous disease: patient compliance and efficacy. Ann Vasc Surg. 2007;21:790-795.

13. Ziaja D, Kocełak P, Chudek J, et al. Compliance with compression stockings in patients with chronic venous disorders. Phlebology. 2011;26:353–360.

14. Eklöf B, Rutherford RB, Bergan JJ, et al; American Venous Forum International Ad Hoc Committee for Revision of the CEAP Classification. Revision of the CEAP classification for chronic venous disorders: consensus statement. J Vasc Surg. 2004;40:1248-1252.

15. Huskinsson EC. Measurement of pain. Lancet. 1974;2:1127-1131.

16. Raju S. Compliance with compression stockings in chronic venous disease. Phlebolymphology. 2008;15:103-106.