Pelvic congestion syndrome: an update

Santiago Zubicoa Ezpeleta1

Michel PERRIN2

Spain

2. Clinique du Grand Large, Chassieu, Lyon,

France

ABSTRACT

Pelvic congestion syndrome is a common cause of chronic pelvic pain in women caused by abnormal ovarian and pelvic varices. The diagnosis is established using Duplex ultrasonography followed by selective venography according to an investigation algorithm, in order to obtain anatomic and hemodynamic information. This allows the precise detection of any anomaly present and whether it is responsible for the symptoms of pelvic congestion syndrome. If treatment is indicated, a number of options are available, but endovenous procedures are usually the first-line treatment as they provide clear benefits over conventional surgery. Further prospective randomized studies are needed to optimally refine this technique and assess long-term patient outcomes.

BACKGROUND

In the mid-19th century, the association between chronic pelvic pain and the presence of varicose veins in the utero-ovarian plexus was noted by Richet who also described the presence of pelvic varices.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Pelvic congestion syndrome (PCS) is a common condition and reports indicate that more than one-third of women will experience pain in the lower abdomen at some point during their life.1

ETIOLOGY, PATHOLOGY, AND PHYSIOPATHOLOGY

Two venous systems are known to be involved in PCS: the ovarian and internal iliac veins. Incompetence in these veins is responsible for reflux and varices in various internal iliac vein tributaries or in the lower extremities. Ovarian vein and internal vein tributary incompetence may have several different etiologies. Congenital incompetence is caused by the absence of valves. The main cause of secondary incompetence is multiparity, but ovarian dilatation and reflux may also be due to compression as a result of abdominal or retroperitoneal tumors (benign or malign), nutcracker syndrome (left ovarian vein), or iliac vein compression. The most frequent type of compression is compression of the left common iliac vein, also known as May-Thurner syndrome.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Pain may or may not be associated with other symptoms such as pelvic heaviness, dyspareunia, dysmenorrhea, lumbar pain, urinary frequency, signs of vulvar and lower limb varices, and hemorrhoids. It is accepted that these symptoms must be present for at least 6 months before a diagnosis of PCS can be considered.

PELVIC CONGESTION SYNDROME INVESTIGATION

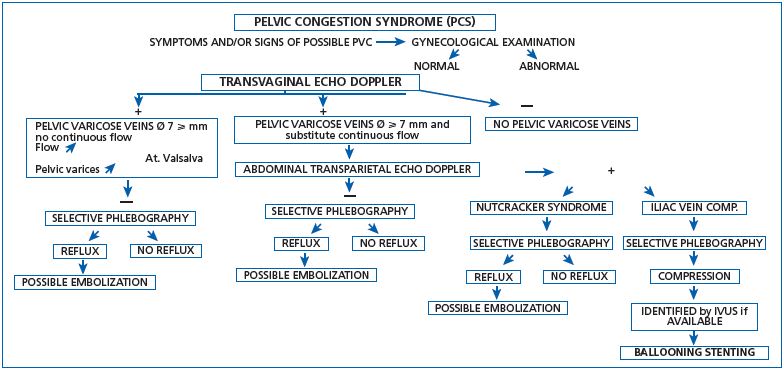

Many protocols can be used to identify the presence of PCS and no comparative trials have been carried out so far. Nevertheless, there is a general consensus that selective venography is the best procedure to identify the anatomical and pathophysiological anomalies of PCS. However, as selective venography is an invasive procedure, investigations should begin with a noninvasive duplex scan, which may give clues indicative of PCS. In our practice, we use an investigation algorithm when female patients consult with the signs and symptoms mentioned above (Figure 1).2

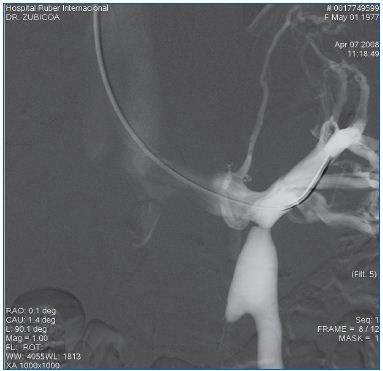

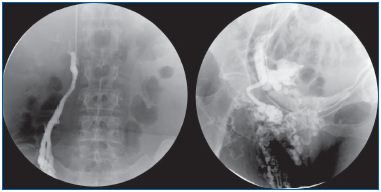

The first step is to rule out any gynecological disease or pudendal nerve compression, which is less common. Once these conditions have been excluded, transvaginal echo Doppler (TED) ultrasonography should be performed. This investigation provides both anatomical and hemodynamic information. If pelvic varices with substitute continuous flow that cannot be modified by the Valsalva maneuver are identified, the next step is to perform abdominal transparietal echo Doppler (ATED) ultrasonography to determine if there is vein compression. ATED can identify either left renal vein compression or, more frequently, iliac vein compression. When compression is identified by ATED, complementary venography is undertaken to distinguish between left renal vein compression with ovarian reflux (Figure 2) and iliac vein compression with reflux in the internal iliac vein tributaries (Figure 3).

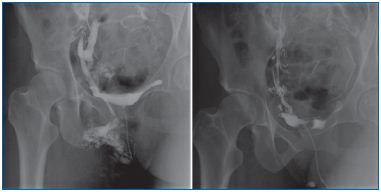

Conversely, for pelvic varices without continuous flow but displaying flow augmentation and dilatation induced by the Valsalva maneuver during TED, selective venography is the recommended next step, as compression is highly unlikely. Brachial access is best for this procedure and will confirm the absence of compression in the left renal vein and iliac vein. The presence of reflux is investigated by selective venography in the gonadal veins (Figure 4) or iliac vein tributaries (Figure 5).

In summary, this investigation algorithm allows a step-by-step and precise determination of the type of anomaly present and whether it is responsible for PCS.

Figure 1. Investigation algorithm for pelvic congestion syndrome.

Abbreviations: Ø, diameter; PVC, pelvic venous congestion ; IVUS, intravascular ultrasound.

Figure 2. Venography using brachial access. Left renal vein

compression is associated with left ovarian vein reflux.

Figure 3. Venography using femoral access showing left

common iliac vein compression and reflux in the left internal

iliac vein tributary.

Figure 4. Venography using brachial access and selective

ovarian vein catheterization. Valsalva maneuver: unilateral

ovarian vein reflux filling pelvic varices through a round

ligament vein as well as lower-limb varicose veins.

Figure 5. Venography using brachial access and internal iliac

vein tributary vein catheterization.

A. Reflux filling both pelvic varices and lower-limb varicose veins

is identified after injection into the internal pudendal vein and

Valsalva maneuver.

B. The same patient, after embolization. There is no longer any

reflux into the internal iliac vein tributary.

Figure 6. Venography using brachial access. Incompetent left

ovarian vein before and after embolization (Amplatzer).

TREATMENT OF PELVIC CONGESTION SYNDROME

Drugs such as medroxyprogesterone and micronized purified flavonoid fraction have been used to provide short-term improvement, but there are no data on longterm efficacy.

Sclerotherapy has been associated with poorly documented and inconclusive results. Various open and laparoscopic surgery techniques have been reported including ovarian or iliac vein ligation or resection. Poor-to-good outcomes in small series have been reported and were published, for the most part, over 10 years ago.

Endovenous treatment with distal embolization of the refluxed veins by a coil and/or foam sclerosing agent (Figure 6), and/or by ballooning and stenting iliac vein compression (Figure 7) has progressively replaced surgery (Table I).3-12

TREATMENT INDICATIONS

The decision to treat PCS is based on the severity of the symptoms as well as the presence of vulvar and lower limb varices. When operative treatment is considered, endovenous procedures are the first-line treatment with clear benefits over conventional surgery as they are less invasive and associated with very few complications and low morbidity.

Figure 7. Venography using femoral access. This is the same

patient as in Figure 3, after stenting. Reflux is no longer

observed.

CONCLUSION

Pelvic congestion syndrome is underestimated and its diagnosis relies on precise investigation techniques. Endovenous treatment is the recommended operative technique to treat this condition.

1. Jamieson D, Steege J. The prevalence of dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, pelvic pain, and irritable bowel syndrome in primary care practices. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;87:55-58.

2. Leal Monedero J, Zubicoa Ezpeleta S, Perrin M. Pelvic congestion syndrome can be treated operatively with good long-term results. Phlebology. 2012;27(suppl 1):65-73.

3. Capasso P, Simons C, Trotteur G, Dondelinger RF, Henroteaux D, Gaspard U. Treatment of symptomatic varices by ovarian vein embolization. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 1997;20:107- 111.

4. Maleux G, Stockx L, Wilms G, Marchal G. Ovarian vein embolization for the treatment of pelvic congestion syndrome: Long-term technical and clinical results. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2000;11:859-864.

5. Venbrux AC, Chang AH, Kim HS, et al. Pelvic congestion syndrome (pelvic incompetence): impact of ovarian and internal vein embolotherapy on menstrual cycle and chronic pelvic pain. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2002;13:171- 178.

6. Pieri S, Agresti P, Morucci M, de Medici L. Percutaneous treatment of pelvic congestion syndrome. Radiol Med (Torino). 2003;105:76-82.

7. Chung MH, Huh CY. Comparison of treatments for pelvic congestion syndrome. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2003;201:131-138.

8. Kim H, Malhotra A, Rowe P, Lee JM, Venbrux AC. Embolotherapy for pelvic congestion syndrome: long-term results. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2006;17:289-297.

9. Creton D, Hennequin L, Koihler F, Allaert FA. Embolization of symptomatic pelvic veins in women presenting with non-saphenous varicose veins of pelvic origin—threeyear follow-up. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2007;34:112-117.

10. Kwon SH, Oh JH, Ko KR, Park HC, Huh JY. Transcatheter ovarian vein embolization using coils for the treatment of pelvic congestion syndrome. Cardiovasc Interv Radiol. 2007;30:655-661.

11. Gandini R, Chiocchi M, Konda D, Pampana E, Fabiano S, Simonetti G. Transcatheter foam sclerotherapy of symptomatic female varicocele with sodium-tetradecyl-sulfate foam. Cardiovasc Interv Radiol. 2008;31:778- 784.

12. Asciutto G, Asciutto KC, Mumme A, Geier B. Pelvic venous incompetence: reflux patterns and treatment results. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2009;38:381- 386.