Stripping of the great saphenous vein under micronized purified flavonoid fraction (MPFF) protection (results of the Russian multicenter controlled trial DEFANCE)

Victor S. SAVELJEV2

Anatoly V. POKROVSKY1

Alexander I. KIRIENKO2

Vadim YU. BOGACHEV2

Igor A. ZOLOTUKHIN2

Sergey V. SAPELKIN1

SUMMARY

This paper presents the results of the DEFANCE study (Daflon 500 mg* – assEssment of eFficacy ANd safety for Combined phlEbectomy study).

The aim of the study was to compare the intensity of postoperative pain, the size of postoperative hematoma, and quality-of-life score between two groups of patients:

• a MPFF at a dose of 500 mg group: patients who underwent stripping of the great saphenous vein (GSV) and were treated with MPFF at a dose of 500 mg 14 days before and 30 days after surgery

• a control group: patients who underwent stripping of the GSV and were not treated with MPFF at a dose of 500 mg

The study enrolled 245 patients with varicose vein disease who underwent unilateral stripping of the GSV in combination with stab avulsion. The treatment group (n=200) received micronized purified flavonoid fraction (MPFF, MPFF at a dose of 500 mg, 1000 mg/day) for 2 weeks before and 30 days after the procedure; the control group (n=45) did not receive MPFF at a dose of 500 mg in the pre- and postoperative periods.

Pain severity was assessed by means of a 10-point visual analog scale (VAS) and an original 12-point scale was used to evaluate subcutaneous hematomas in the medial aspect of the thigh (zone of the GSV stripping). Subjective symptoms and quality of life were evaluated 7, 14, and 30 days after the procedure.

Subjective symptoms and the area of subcutaneous hematomas were significantly lower in the MPFF at a dose of 500 mg group than in the control group: 7 days after the procedure, VAS scores were 2.9 and 3.5, respectively and hematoma area 3.4 and 4.6 points, respectively. The same trend was observed for limb heaviness and fatigue, evidencing the better exercise and orthostatic tolerance of patients of the MPFF at a dose of 500 mg group in the early postoperative period. Quality of life assessment by means of CIVIQ, a chronic venous insufficiency questionnaire, failed to reveal statistically significant differences between the MPFF at a dose of 500 mg and control groups in 4-week postoperative follow-up.

Micronized purified flavonoid fraction (Detralex, MPFF at a dose of 500 mg) in the pre- and postoperative period after phlebectomy attenuated pain, decreased postoperative hematomas, and accelerated their resorption, thus increasing exercise tolerance in the early postoperative period.

INTRODUCTION

Stripping in combination with stab avulsion is a current basic principle of lower limb varicose vein (VV) management. According to cumulative worldwide experience, stripping is a commonly used safe and radical procedure in most cases. Nevertheless, the principles and technique of stripping have been revised repeatedly throughout the history of VV surgery. Different types of removal technique have been suggested for major veins and their tributaries, as well as variants of ligation for perforating veins.1-4 Several generations of surgeons have made numerous improvements not only in efficacy, but also in surgical safety. The current technique of phlebectomy achieves a reasonable balance between radical surgery and minimal invasiveness, providing a noticeable decrease in postoperative complications. Long-lasting unsightly scars, septic complications, lymphorrhea, and serious motor or sensory deficits are things of the past.

Given the impressive achievements of vascular surgery, it is natural to inquire whether phlebectomy has become an ideal procedure. The answer, unfortunately, is no. It is human to put forward less noteworthy problems as soon as more essential tasks have been solved. The absence of severe postoperative complications was long considered the main criterion of success among phlebologists, but patients evaluate our work by quite different measures. About 70% to 80% of patients suffer from postoperative pain and hematomas,5 while some authors point out that subcutaneous bruising is present in absolutely all patients after phlebectomy.6

Such criteria as leg pain, heaviness, and massive bruises are very important for patients, though phlebologists may pay little attention to these complaints, considering them quite “natural” in the postoperative period. These are the very parameters that became primary end points of the multicenter, open-label, nonrandomized DEFANCE (Daflon 500 mg – assEssment of eFficacy ANd safety for Combined phlEbectomy) study carried out in 2006 in 9 Russian surgical clinics located in Ekaterinburg, Krasnoyarsk, Moscow, Omsk, Samara, St Petersburg, Stavropol, Rostov-on-Don, and Riazan.

The main objective of the trial was to refine the role of venoactive drug therapy in postoperative care of patients with VV, treated with high stripping in combination with stab avulsion. The theoretical principles of the study were based on the well-known analgesic, antiedematous, and venotonic effects of MPFF at a dose of 500 mg. We suggested that the first two effects could provide pain relief after phlebectomy, while the elevation of venous tonus can decrease hemorrhage volume after high stripping of the GSV.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The main inclusion criteria were as follows:

• female

• age 25-60 years

• C2 CEAP clinical class

• ultrasound angiological features of reflux in the GSV

• clinical symptoms (heaviness, fatigue, and others)

• unilateral lesion of GSV

• the absence of varices in GSV tributaries in the thigh

• the absence of phlebotropic therapy 8 weeks prior to inclusion

Patients were assessed 4 times: 2 weeks before surgery (D- 14), and 7, 14 and 30 days after the procedure (D7, D14 and D30, respectively). The first assessment included the measurement of pain severity, heaviness and fatigue, tingling, and night leg cramps by 10-point VAS. Disease history focused on the existence of risk factors and of previous treatment for chronic venous disease. Severity of VV-related physical and emotional discomfort was measured by quality of life tool specific for the VV disease (CIVIQ.)

After inclusion, patients of the treatment group (n=200) received MPFF at a dose of 500 mg orally (500 mg, bid for 6 weeks). So, patients were treated for 2 weeks prior to surgery and for 4 weeks after surgery. The control group (n=45) received no phlebotropic agents in the pre- and postoperative period.

In order not to interfere with the formation of hematoma, no antithrombotic prophylaxis was given whatever the group. Compression class 2 (20-30 mm Hg) was prescribed during 4 weeks postoperatively in patients of both groups.

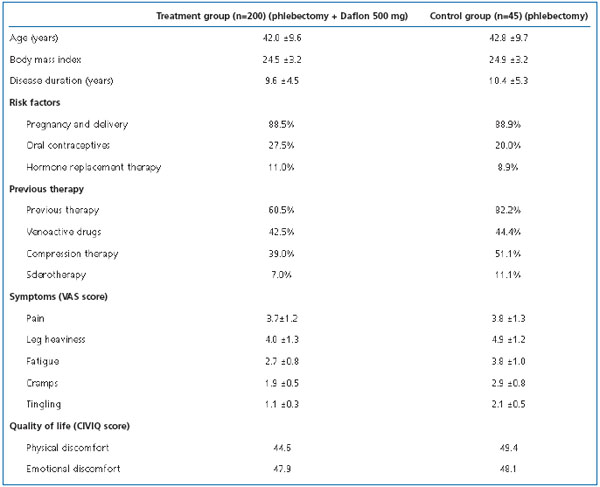

Group characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Demographic and baseline clinical characteristics of patients.

Before the procedure, all varicose veins scheduled for removal and incompetent perforating veins of the medial group on the leg were marked upon the skin. The procedure was carried out under general or spinal (peridural or conduction) anesthesia. According to the inclusion criteria, phlebectomy was restricted to GSV short stripping (to the upper third of the lower leg), microphlebectomy of leg varicose veins and ligation of incompetent Cockett perforating veins through small incisions. Cases of total GSV removal were excluded from the trial, because venous trunk extraction can be accompanied by neural damage and development of special pain syndrome. Invagination or the conventional Babcock technique was used for GSV stripping.

Postoperative follow-up included assessment of subjective symptoms and quality of life. The area of hematoma in the projection of the removed GSV (in inguinal, femoral and upper-third of the lower leg zones) was measured by a special scoring method. The whole specified zone was divided into 12 segments by several notional lines perpendicular to the limb long axis: along the inguinal fold, adjacent to the upper and lower edges of the patella and adjacent to the upper edge of the proximal access to GSV in the shin upper third of the lower leg (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Schematic division of limb into segments to determine the area of postoperative hematomas.

The segment between the inguinal fold and the patella was divided into 9 segments by 2 transverse and 2 longitudinal lines (in anterior-medial and posteriormedial parts of the thigh) (Figure 1). So, the whole area was divided into 12 segments (including the zone above the inguinal fold). Bruises in each segment were given 1 point, and the total hematoma score was calculated as a sum of all involved segments. Division of the area of phlebectomy into segments was difficult, so limbs were photographed digitally, with subsequent computer analysis of images.

Statistical analysis was carried out in the State Research Institute of Preventive Medicine with the SAS statistical program (Version 6.12).

RESULTS

The treatment (MPFF at a dose of 500 mg) and control groups had similar baseline demographic and clinical parameters including age, body mass index, disease duration, and extent (Table 1). There was minor difference in occurrence of VV risk factors. Patients of the MPFF at a dose of 500 mg group were more often exposed to regular orthostatic loads due to standing or sitting during work, and more often used estrogen/ progestagen drugs for contraception or hormone replacement therapy. Nevertheless, clinical symptoms (excluding leg pain) were more severe in the control group. This was probably related to more active previous treatment of venous stasis in the control group, compared with the MPFF at a dose of 500 mg group.

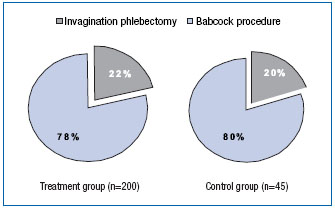

Surgical strategy was similar in the two groups (Figure 2). The Babcock technique was used in the majority of interventions; invagination stripping accounted for one fifth of all procedures. The typically incompetent Cockett perforating vein was ligated in the lower leg in 35% of patients in the MPFF at a dose of 500 mg group and in 37.8% of patients in the control group. The perforating vein in the middle third of the leg was transected and ligated in 45.5% and 51.1% of patients in the MPFF at a dose of 500 mg and control groups, respectively.

Figure 2. Type of saphenectomy.

Different types of analgesia were similarly frequent in the two groups. The modern technique of motor and sensory innervation blockade (spinal, peridural, and conduction blocks) was used in 78% and 76% of patients in the MPFF at a dose of 500 mg and control groups, respectively. General anesthesia was used in the remaining cases. The postoperative period was uneventful in all 245 patients. Minor adverse effects (gastric irritation) of MPFF at a dose of 500 mg appeared in 4 cases (1.6%) during the first 2 weeks of administration and resolved spontaneously. No cases of venous thrombotic complications, delayed wound healing, or peripheral neural damage were observed.

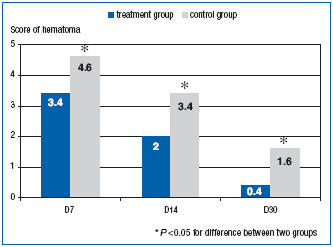

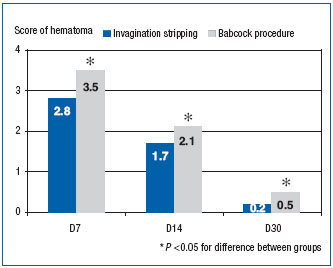

At the same time, subcutaneous hemorrhage and subjective symptoms were less pronounced in the MPFF at a dose of 500 mg group, according to the main end points–hemorrhage size (Figure 3) and pain severity (Figure 4).

Figure 3. Postoperative hematoma area (points on original scale, see text).

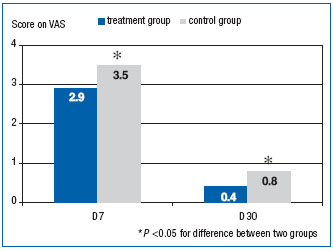

Figure 4. Pain severity in postoperative period (points on visual analog scale).

Postoperative hematoma area in the MPFF at a dose of 500 mg group was smaller than in the control group throughout the follow-up period. Seven days after the procedure, the mean area of hematomas was 3.4 points in the MPFF at a dose of 500 mg group and 4.6 points in the control group (P<0.05). Furthermore, the difference gradually increased: 26% on D7, 40% on D14, and 70% at the end of the trial, showing that the phlebotropic agents accelerated hematoma resorption.

The difference in pain severity was most prominent 7 days after the procedure (Figure 4). At this time point the mean VAS score was 2.9 in the MPFF at a dose of 500 mg group and 3.5 in the control group (P<0.05). One week later (D14), pain was less severe in both groups and was practically absent at the end of the trial.

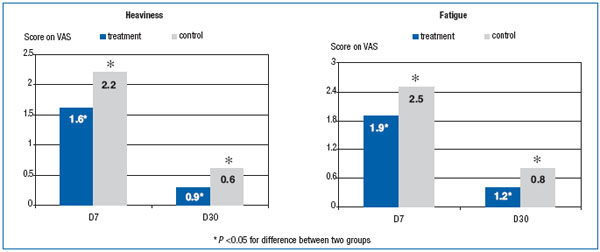

Interesting trends were observed in subjective criteria, such as heaviness and fatigue of the operated limb (Figure 5). These complaints (along with pain) are most typical for patients after phlebectomy. Leg heaviness and tiredness after walking usually develop early in the postoperative period. These symptoms were less severe in the MPFF at a dose of 500 mg group, indicating better orthostatic tolerance.

Figure 5. Heaviness and fatigue of operated legs (points on visual analog scale).

In our opinion, though pain severity, limb heaviness, and fatigue were more pronounced in the control group at baseline, this fact had little impact on the cumulative results of the trial. Postoperative pain, as well as limb heaviness and fatigue, has a quite different cause than the same symptoms caused by venous stasis.

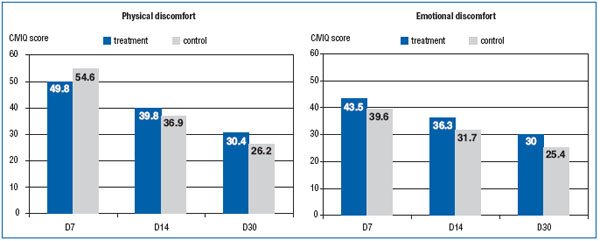

Quality of life scores measured by CIVIQ in the preoperative period (Table 1) and in 4-week follow-up were similar in the two groups (Figure 6). It should be mentioned that this scale is intended for patients with chronic venous disease, while the postoperative period specifically alters a patient’s condition. Disturbing symptoms after phlebectomy are usually related to surgical trauma, wound healing, and round-the-clock wearing of compressive bandages, rather than to venous pathology. Despite the use of CIVIQ to assess quality of life after surgery in previous trials,7-9 we did not find any changes in the patients’ physical and emotional state after the intervention using this tool.

Besides the main aim–to assess the efficacy of venoactive drugs in pre- and postoperative management of phlebectomy patients–our study had some secondary objectives worthy of attention for surgeons who specialize in venous pathology. We analyzed the correlation between main outcome measures (pain severity and hematoma area) on the one hand and type of phlebectomy or anesthesia on the other.

Figure 6. Time trends in quality of life (physical and emotional discomfort) in postoperative period (points on CIVIQ).

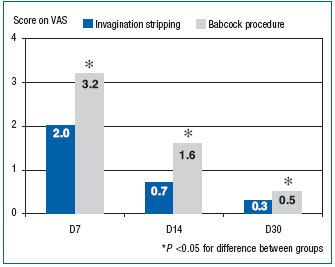

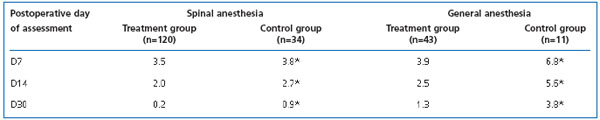

Invagination stripping is considered less invasive than the conventional Babcock technique of GSV trunk removal, and our results prove this point. Pain severity and hematoma area were compared in patients of the MPFF at a dose of 500 mg group who underwent different types of GSV stripping (Figures 7 and 8). Invagination stripping yielded more beneficial results in terms of both parameters.

Figure 7. Pain severity in postoperative period according to the type of saphenectomy (points on visual analog scale).

Figure 8. Postoperative hematoma area according to the type of saphenectomy (points on original scale).

According to the world of anesthesiological practice, spinal (epidural, conduction) anesthesia is accompanied by an increased risk of hemorrhagic events, because peripheral neural block elicits dilatation of the arterial and venous vasculature. Nevertheless, we failed to reveal any difference in hematoma area in patients operated under this type of anesthesia. Furthermore, subcutaneous hemorrhage was less extensive in this subgroup than in patients who had surgery under general anesthesia. Naturally, in subgroups of both spinal and general anesthesia, mean hematoma area was lower in those patients who received micronized diosmin (Table 2).

Table 2. Postoperative hematoma score according to type of anesthesia (points on original scale, see text).

In summary, our study demonstrates that invagination stripping of GSV must become a key technique of modern phlebectomy. Different variants of peripheral neural blockade can be considered the anesthesiological method of choice for these procedures. And, finally, it is clear that micronized diosmin can be an essential part of pharmacological preoperative care and postoperative recovery for patients with VV who undergo phlebectomy. This venoactive drug helps to attenuate pain, to decrease postoperative hematomas and accelerate their resorption, and to increase exercise tolerance in the early postoperative period.

Besides, according to our cumulative experience of patients with chronic venous insufficiency, preoperative management should include prolonged administration of MPFF at a dose of 500 mg (for 4-6 weeks) and compressive therapy in cases of VV with manifest indurated cellulitis and lymphostasis. Postoperatively, this therapy should be continued for at least 4 weeks.

REFERENCES

2. Muller R. Treatment of varicose veins by ambulatory phlebectomy. Bulletin de la Société Française de Phlebologie. 1966;19:277- 279. In French

3. Staelens I, Van der Stricht J. Complication rate of long stripping of the greater saphenous vein. Phlebology. 1992;7:67-70.

4. Kudikin M. New approach to varicose vein surgery. Abstracts Book of the International Surgical Congress “New technologies in Surgery Field”. Rostov-on Don, 5-7/10/2005, pp.295-296.

5. Pittaluga P, Marionneau, Creton D et al. Surgical treatment of varices: a modern approach. Int Angiol. 2005;24:67.

6. Neumann H.A. Hematomas are underrepresented in studies on complications of ambulatory phlebectomy. Dermatol Surg. 2002;28:544-545.

7. Raju S, Owen S Jr, Neglen P. The clinical impact of iliac venous stents in the management of chronic venous insufficiency. J Vasc Surg. 2002;35:8-15.

8. Veverkova L, Kalac J, Jedlicka V, Wechsler J. Analysis of surgical procedures on the vena saphena magna in the Czech Republic and an effect of MPFF at a dose of 500 mg during its stripping. Rozhl Chir. 2005;84:410-412,414- 416. In Czech.

9. Przybylska M, Majewski W. Varicose veins of lower limbs is a very common medical problem in developed countries and also in Poland. Pol Merkur Lekarski. 2005;18:657- 662. In Polish.