Suspicion of deep vein thrombosis – diagnostic strategy at the interface of general practice and specialist care

Medicine/Family Medicine,

Georg-August-University Goettingen,

Germany

SUMMARY

Aim: We describe the characteristics of patients with suspected deep vein thrombosis (DVT) referred to specialists by their general practitioner (GP) and the further management by the specialist.

Patients and method: From August 2001 to April 2003, 114 patients (age 15 to 91, 72 women) with suspected symptoms of DVT were prospectively recruited from a specialist practice for vascular surgery/phlebology. Symptoms and clinical findings were documented by a standard procedure.

Results: Forty percent of the patients received compression therapy and 18% anticoagulation with heparin by their GP. Pain (88%) and swelling (71%) were the leading patient complaints. Physical examination revealed calf pressure pain (40%) and differences in calf circumference (56%) as the dominant results. The clinical signs themselves were not specific enough to exclude DVT. DVT was diagnosed in 12 patients (10.5%). Varicosis (30%) and (pseudo-) radicular pain (20%) were the most frequent differential diagnoses.

Conclusion: The proportion of diagnosed DVT in patients referred by their GPs was low. Clinical examination alone was unsuitable to detect DVT. Therefore, GPs are not able to exclude the diagnosis of DVT without technical diagnostics. The use of D-Dimer tests in connection with clinical signs could be an alternative for GPs to reduce referrals, although this concept has not yet been evaluated in a primary-care setting.

INTRODUCTION

Improvements in the diagnosis and treatment of deep venous thrombosis (DVT) in the past decade have induced a shift from inpatient to outpatient treatment. This development attaches great importance to cooperation between general practitioners (GPs) and specialists.1 Nevertheless, until now, GP’s procedures for treating patients with a suspicion of DVT have been poorly investigated, which might be a consequence of the relatively low incidence of thromboembolic events in the primary care setting.2

The leading problem for GPs in diagnosing DVT is that a physical examination can rarely exclude the possibility of a DVT. This problem is very serious in view of the potentially lethal course of the disease.3-6 Imaging diagnostics are predominantly the domain of specialists. Therefore, in the case of clinical suspicion of DVT, a referral is presently the only opportunity to confirm or rule out the diagnosis.

Because of the small incidence of DVTs in the primary care setting, it requires great effort to include a sufficient number of patients from general practices to analyze patient characteristics. Therefore, we acquired patients with a suspicion of DVT referred by their GPs to a specialist (phlebologist) which allowed us to gather a higher number of patients in a shorter period. We characterized these patients with regard to symptoms, complaints, and previous therapy. The aim of the study was to verify the significance of physical examination results in diagnosing DVT compared with specialists’ diagnoses based on imaging diagnostics. Furthermore, we analyzed the frequency of the differential diagnoses and whether there were typical patterns of complaints and symptoms, allowing for a differentiation between these diagnoses.

METHODS

From August 2001 to April 2003, all 114 patients (age 15 to 91, 72 women) with suspected symptoms of DVT who had been referred from a GP to a specialist practice for vascular surgery/phlebology were prospectively recruited for this study. Only patients with a tentative diagnosis made by their GPs were included. The completeness of patient inclusion was controlled by a comparison with electronic medical data. Symptoms and clinical findings were documented by a standard procedure. The interval between a GP’s referral and the specialist visit in our center was no more than 1 day.

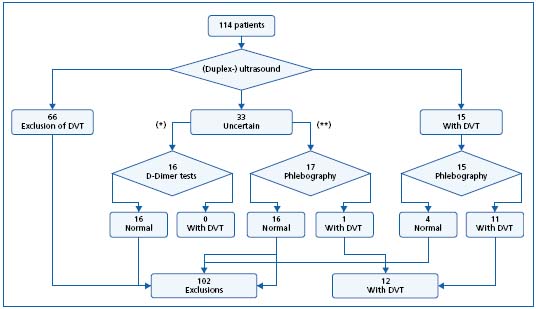

The further diagnostic process was not specified by a study protocol. Phlebologists were free in their decisionmaking. Thus, all patients were examined using (duplex-) ultrasound of the venous system of the legs (in accordance with the actual guidelines of the German association for phlebology).7 In divergence from the guidelines, phlebography was added in all patients with a suspicion of DVT in the ultrasound or proven thrombosis. In case of an uncertain ultrasound (eg, in adiposity, massive edema), the further procedure depended on clinical probability of DVT in accordance to Wells et al.8 In patients with a low clinical probability, a D-Dimer test was added (SimpliRED(r) D-Dimer, Hämochrom Diagnostica GmbH, Essen). In case of medium or high probability, phlebography was added routinely. The diagnostic process is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Diagnostic proceeding in 114 patients referred by their general practitioner with suspicion of deep venous thrombosis (* = low clinical probability of DVT, ** = medium or high probability).

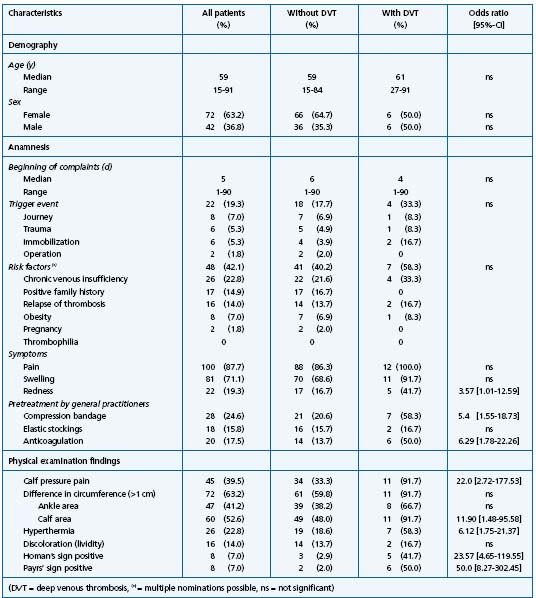

Table I. Characteristics of 114 patients referred by their general practitioner with suspicion of deep venous thrombosis (given are total number and percentage, odds ratio with 95% – interval of confidence).

Data were processed using SAS 8.1.9 Multiple logistic regression models were used to test for associations between patient characteristics, symptoms, and diagnoses (_ = 0.05). The degree of effect is reported as odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Due to the limited number of patients included, the following data analysis is only explorative.

RESULTS

Patients’ characteristics were demonstrated in Table I. The first symptoms were reported 3 months before the visit in one case, but the majority of patients visited their GPs with recently occurring symptoms. In less than 20% of the patients, a “classical” trigger event of thrombosis (eg, immobilization, trauma) could be detected by anamnesis. In 40% of the patients, compression therapy was started by the GPs, partially by application of an elastic stocking. Anticoagulation with heparin was started by GPs in 17.5% of all cases; 13% of the patients received both compression therapy and an anticoagulation.

The further diagnostic procedures of the specialists are represented diagrammatically in Figure 1. Thirty-three patients with an uncertain ultrasound received a supplementary D-Dimer test or phlebography. In one case, the additive phlebography showed calf-vein thrombosis. Sensitivity of the (duplex-) ultrasound was calculated as 0.92 (including the uncertain cases). In 3 patients, the initially pathologic result of the ultrasound could not be confirmed using phlebography. The resulting specificity of the ultrasound was 0.96, the positive predictive value 0.73, and the negative predictive 0.99.

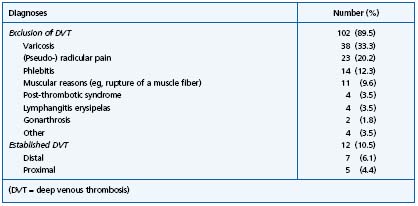

In patients without verifiable thrombosis, varicosis and (pseudo-) radicular pain were the most frequent diagnoses (Table II). The classification “other diagnoses” included eg, (nocturnal) calf cramps, and in two cases no certain diagnosis could be made. In patients with the differential diagnosis (pseudo-) radicular pain, the symptoms and complaints differed significantly from those patients with established thrombosis. They showed less typical thrombosis signs, eg, swelling (Odds ratio (OR) 0.08, 95% – Confidence interval (CI) 0.03-0.22]), redness (OR 0.82 [0.75-0.91]), local hyperthermia (OR 0.71 [0.62-0.82], difference in ankle circumference (OR 0.04 [0.01-0.34]) and in calf circumference (OR 0.13 [0.04- 0.42]). Patients with the diagnosis “varicosis” complained more frequently of swelling (OR 7.23 [2.04-25.66], but less frequently about pain (OR 0.06 [0.01-0.26]) and redness (OR 0.71 [0.62-0.82]). The classic signs of thrombosis such as calf pressure pain or Homan’s sign showed no significant difference between patients with and without established thrombosis, and are therefore inappropriate to exclude DVT from those with (pseudo-) radicular pain or varicosis.

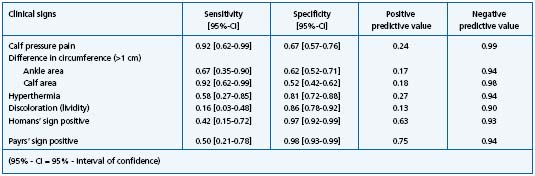

In 73% of the patients, the physical examination showed at least one classical sign of thrombosis. Table III shows the discriminatory power of these classical signs. Multiple regression analyses based on physical examination results were performed, but results should be interpreted carefully due the small number of included patients with established DVT. The (max-rescaled) R-square resulted in 0.56. The sensitivity of the model was 0.92, and the specificity 0.87. Corrected for the study prevalence, the positive predictive value resulted in 0.46, the negative in 0.99. The area under the curve (AUC) was 0.90. A crossvalidation basing on the same sample detected 11 out of the 12 patients with established DVT correctly.

Table II. Differential diagnoses of 114 patients referred by their general practitioner with suspicion of deep venous thrombosis.

Table III. Test criteria of clinical signs in 114 patients referred by their general practitioner with suspicion of deep venous thrombosis.

DISCUSSION

Physical examination and diagnostic procedure

The proportion of patients with an established DVT (11%) seemed to be low compared with international data basing on patients referred by primary care institutions to specialists (16% to 25%).8,10 This might be influenced by the fact that other investigations studied patients referred to tertiary care institutions, whereas we studied patients with suspicion of DVT in an ambulatory setting.

In all patients, physical examination was followed by an extensive diagnostic procedure. Generally, a (duplex-) ultrasound was performed, a technique which is a very sensitive method (sensitivity varying from 0.62 to 0.97).3,11 Nevertheless, in 28% of the included patients, the result was classified as “cannot be judged with sufficient accuracy” and additional diagnostics were needed (D-Dimer concentration, phlebography). Other investigations found a relevant proportion of insufficiently classifiable patients too and the significance of the positive predictive value is limited (6.21).12-14 The noticeable high proportion of phlebographies used here compared with other recent studies comes from the specialists’ practical experience with false-positive sonography results.

The explanatory power of the calculated regression model was relatively high (AUC 0.90) but cross-validating the model on the same sample showed that 1 out of the 12 patients with established DVT was not identified (false-negative). Therefore, confirming or ruling out the diagnosis of DVT is not possible based only on clinical signs or patients’ symptoms, although the included patients had been prescreened by their GPs. This is in line with other studies reporting the limitations of clinical signs (eg, the high sensitivity of “calf pressure pain” combined with a moderate specificity).3,4 Richards et al showed the high value of the sensitivity of the “difference in calf circumference,” too.15 The “Homans” sign, which has been termed as appropriate for diagnosing DVT in recent investigations, was of low sensitivity in our study.3 The shared problem of most studies investigating clinical signs in DVT is the low number of included patients, which affects the significance.16

D-Dimer test

In the 1990s, a bedside D-Dimer test became available. It is characterized by a high sensitivity combined with a moderate specificity. This test makes it possible to use D-Dimer testing in an ambulatory setting, and is often used in combination with physical examination results or sonography diagnostics.5,17,18 The often-cited studies by Perrier et al, Kearon et al, and Wells et al are all based upon preselected patient collectives in hospital outpatient care centers.10,17,19 Until now, research based upon unselected patients in a primary care setting is lacking. Since important test criteria (eg, the predictive values) are dependent on disease prevalence, the use of D-Dimer tests has not been evaluated in the primary care setting.20,21 Nevertheless, the prior use of D-Dimer tests in combination with a clinical score (eg, the Wells score) is probably a valuable way to economize health system resources.22 Therefore, we would seriously recommend a study of the use of bedside D-Dimer tests in the primary care setting.

General practitioners’ initial treatment

Less than one fifth of the included patients received anticoagulation therapy before their referral to the specialist. Until now, it has been unclear whether anticoagulation should be started already in patients under suspicion of DVT or whether the definitive diagnosis should be awaited. The risk of a bleeding complication must be balanced with the potential benefits (eg, the prevention of an embolic complication). A systematic study investigating the use of anticoagulants in patients under suspicion of DVT does not exist to the best of our knowledge. Furthermore, there is no explicit information about the incidence of thromboembolic complications in the first 24 hours after the DVT onset (which is the maximum space of time until patients saw a specialist in our investigation). A recent recommendation published in a German journal suggested the early use of anticoagulants based on the low complication rates of heparins.1 In our study, GPs obviously orientated themselves on the clinical probability of DVT, since those patients with a DVT established by further examination were more likely to receive anticoagulation therapy compared with those patients with excluded DVT (OR 6.3 [1.8-22.3]). In our investigation, no patient developed symptoms of a pulmonary embolism in the space of time before reaching the specialist, but the low number of included patients does not allow these results to be generalized.

Compression therapy is – in addition to symptomatic pain therapy – another pillar of acute therapy in DVT. In this study, about 40% of the patients received a compression therapy. This therapy should inhibit thrombus growth by accelerating the venous flow, and should fix the thrombus locally.1,23,24 However, these assumptions are based on pathophysiological considerations and experimental studies. Until now, randomized controlled trials investigating the impact of compression therapy under acute conditions are still lacking.

CONCLUSIONS

The prevalence of 10.5% of patients with DVT in our investigated group of patients (already filtered by their GPs) must be considered as low compared with other recent studies. This is again an indicator that GPs work in a field of low incidence, but are confronted here with a potentially lethal disease. Since important test criteria (eg, the predictive values) are dependent on disease prevalence, the transferability of study results established in secondary or tertiary care must be considered as questionable.

Although some clinical signs – like the difference in ankle and in calf circumference and calf pressure pain – showed a high negative predictive value, it was not possible to exclude DVT from the investigated patients with a sufficient certainty. The combination of clinical scores with the D-Dimer test might be a diagnostic alternative to exclude DVT, but has not yet been evaluated in a primary care setting. Deficits in GPs’ initial treatment (eg, less than 50% of the patients received compression therapy) clearly show that there is room for improvement in the cooperation between GPs and specialists.

This article is a translation of the original article published in the journal Phlebologie: Fischer Th, Hähnel A, Schlehahn F, et al. Verdacht auf tiefe Beinvenenthombose. Phlebologie. 2004;33:47-52. It is published here with the kind permission of Cornelia Pfeiffer, Schattauer GmbH, Stuttgart.

REFERENCES

2. Kerek-Bodden H, Koch H, Brenner G, Flatten G. Diagnostics and investment in therapy in primary care patients (in German). Zärztl Fortbild Qualsich. 2000;94:21-23.

3. Ebell MH. Evaluation of the patient with suspected deep vein thrombosis. J Fam Pract. 2001;50:167-171.

4. Kahn SR. The clinical diagnosis of deep venous thrombosis. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:2315-2323.

5. Tatò F. Diagnostic strategies in venous thromboembolism (in German). Phlebologie. 2002;31:150-155.

6. Tovey C, Wyatt S. Diagnosis, investigation, and management of deep vein thrombosis. BMJ. 2003;326:1180-1184.

7. Blättler W, Partsch H, Hertel T. Guidelines of diagnostics and therapy of deep vein thrombosis (in German). Phlebologie. 1998;27:84-88.

8. Wells PS, Hirsh J, Anderson DR, et al. A simple clinical model for the diagnosis of deep vein thrombosis combined with impedance plethysmography. J Intern Med. 1998;243:15-23.

9. SAS Institute Inc. SAS/STAT. User´s Guide Version 8, Cary, NC: 1999.

10. Wells PS, Anderson DR, Rodger M, et al. Excluding pulmonary embolism at the bedside without diagnostic imaging. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135:98-107.

11. Dietrich CF, Bauersachs RM. Sonographical diagnostic of thrombosis (in German). Dtsch Med Wschr. 2002;127:567-572.

12. Noren A, Ottosson E, Sjunnesson M, Rosfors S. A detailed analysis of equivocal duplex findings in patients with suspected deep venous thrombosis. J Ultrasound Med. 2002;21:1375-1383.

13. Eskandari MK, Sugimoto H, Richardson T, Webster MW, Makaroun MS. Is color-flow duplex a good diagnostic test for detection of isolated calf vein thrombosis in highrisk patients? Angiology. 2000;51:705-710.

14. Wells PS, Anderson DR, Bormanis J, et al. Value of assessment of pre-test probability of deep vein thrombosis in clinical management. Lancet. 1997;350:1795-1798.

15. Richards KL, Armstrong JD, Tikoff G, et al. Noninvasive diagnosis of deep vein thrombosis. Arch Intern Med. 1976;136:1091-1096.

16. Anand SS, Wells PS, Hunt D, et al. Does this patient have deep vein thrombosis? JAMA. 1998;279:1094-1099.

17. Kearon C, Ginsberg JS, Douketis J, et al. Management of suspected deep venous thrombosis in outpatients by using clinical assessment and D-Dimer testing. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135:108-111.

18. Kelly J, Hunt BJ. A clinical probability assessment and D-Dimer measurement should be the initial step in the investigation of suspected venous thromboembolism. Chest. 2003;124:1116-1119.

19. Perrier A, Desmarais S, Miron M, et al. Non-invasive diagnosis of venous thromboembolism in outpatients. Lancet. 1999;353:190-195.

20. Kelly J, Rudd A, Lewis RR, Hunt BJ. Plasma D-Dimers in the diagnosis of venous thromboembolism. Arch Int Med. 2002;162:747-756.

21. Roy P, Berrut G, Leftheriotis G, Ternisien C, Delhumeau A. Diagnosis of venous thromboembolism. Lancet. 1999;353:1446.

22. Wells PS, Anderson DR, Rodger M, et al. Evaluation of D-Dimer in the diagnosis of suspected deep-vein thrombosis. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1227-1235.

23. Bauersachs RM, Lindhoff-Last E, Wolff U, Ehrly AM. Management of deep vein thrombosis (in German). Med Welt. 1998;49:194-214.

24. Ohgi S, Kanaoka Y, Mori T. Objective evaluation of compression therapy for deep vein thrombosis by ambulatory strain-gauge plethysmography. Phlebology. 1994;9:28-31.