The new patient-oriented tools for clinical assessment of pelvic varicose disease

AKHMETZIANOV, MD, PhD

Surgeon of the Department of Vascular

Surgery, Inter-regional Clinical Diagnostic

Center of the Ministry of Health of Russia,

Assistant of the Department of

Cardiovascular and Endovascular Surgery,

Kazan State Medical University of the

Ministry of Health of Russia, Kazan, Russia

Abstract

This article presents a review of patient-oriented diagnostic tools currently used in patients with pelvic varicose veins (pelvic congestion syndrome, PCS), and provides rationale for using disease-specific tools, as highlighted in the international consensus documents on the diagnosis and treatment of PCS. The authors present two original diagnostic tools (the Pelvic Varicose Veins Questionnaire, PVVQ, and the Pelvic Venous Clinical Severity Score, PVCSS) that were recently developed taking into account the clinical course of PCS and validated in accordance with international standards. This article also provides rationale for their use in monitoring of patients’ quality of life (QOL) and severity of disease manifestations and also as unified tools for objective clinical assessment. In addition, the article discusses issues of rational pharmacotherapy for PCS in the context of historical and modern research on this disease and in line with an evidence-based approach. Venoactive drugs (VADs) are described as the only group of agents with proven efficacy and safety in PCS. With the largest accumulated evidence base, micronized purified flavonoid fraction’s (MPFF) advantages in the conservative treatment of PCS are demonstrated. Treatment with MPFF is associated with QOL improvement and a decrease in the severity of disease and each of its symptoms.

Introduction

Chronic venous disease (CVD) is an urgent health care issue and a very common pathological condition with a prevalence of up to 83.6%.1 Pelvic congestion syndrome (PCS) as an independent nosological entity and one of the essential components of CVD is an important problem in modern medicine due to its high prevalence (6%-15% of women of reproductive age), variability in clinical forms, and progressive course of the disease.2-6 The clinical and social significance of PCS is related to a substantial reduction in the quality of life (QOL) of patients, their self-esteem, productive activities, and social relationships, as well as impaired reproductive, marital, and family functions and the lack of a persistent clinical effect after courses of treatment.7-11

Despite significant advances in the diagnosis and treatment of CVD, PCS remains one of the least studied disorders, with a number of aspects that need to be further addressed. These aspects include the terminology used for this disease, generally accepted and convenient classification, and a consensus on clinical and visual criteria.9,12-15 An important issue is the lack of adequate validated patient-oriented tools for the clinical assessment of PCS, namely the specific QOL questionnaires and clinical scales to grade the disease severity. These inadequacies in making the diagnosis of PCS preclude an objective and complete assessment of the effect of any treatment and the comparative analysis of the results of various treatments both in a single institution and in multicenter trials.16-18 The need for patient-oriented tools is highlighted in the consensus documents of the International Union of Phlebology and the Multidisciplinary Research Consensus Panel, as the tools commonly used in PCS assessment are not appropriate for the stated objectives.9,14

The purpose of this work is to review the current state of patient-oriented assessment and pharmacotherapy in PCS, as well as to present new validated tools for the assessment of QOL and severity of PCS in women.

Overview of the current state of patient-oriented diagnostic tools

To date, several QOL questionnaires and standardized rating scales have been developed, tested, and used for the clinical assessment of various diseases. QOL is an integral parameter of the physical, psychological, emotional, and social functioning of an individual, which is based on subjective perception.19,20 This is a complex and multifaceted concept that includes a person’s physical health, mental state, level of personal independence, social relationships, and possibility of self-actualization in social settings.21

Currently, QOL is actively studied and is becoming an indispensable element of the clinical examination of patients, which is used in almost all areas of medicine. It reflects the influence of the pathological process and its treatment on the well-being of the patient and is also an essential integrative indicator to support treatment rationale and secondary prevention of the disease.22 The main tools for assessing QOL are specific questionnaires used as reference instruments to evaluate a particular treatment in the context of a particular disease.

The methodology of QOL and disease severity assessment includes administration of general, specialized, or disease-specific questionnaires that take into account morphological, functional, and psychosomatic factors, as well as special subject-oriented clinical scales, which are focused on the influence of a specific pathological process and the treatment effect on health and severity of disease manifestations.11

General or nonspecific questionnaires are designed to assess QOL regardless of the nosology, severity of the disease, and methods of treatment. The best-known general questionnaires are the Medical Outcomes Study, 36-item short form(MOS SF-36), Euro-Qol, the Quality of Well-Being Index, the Sickness Impact Profile, the Nottingham Health Profile, and the Quality of Life Index. Their advantage is the versatility and multidimensional assessment of QOL components, as well as the possibility of their use in a healthy population.19

Specialized questionnaires provide an assessment not of the health state as a whole, but of its individual aspects. A significant drawback of both general and specialized questionnaires is the lack of consideration of peculiarities of a disease and its treatment and low sensitivity to the QOL changes in a particular disease.23

Specialized questionnaires are focused on the effect of a particular pathological process and treatment on the health state and QOL of an individual. They are most sensitive in assessing particular diseases and contain components specific to those. To date, specialized questionnaires have been developed for almost every disease, and several hundred multicenter randomized studies have been conducted to assess QOL along with other parameters.19 At the same time, no questionnaire specific to PCS could be found in the available literature.

It is believed that the PCS assessment can be performed using the QOL tools developed for CVD, such as the Chronic Venous Insufficiency Questionnaire (CIVIQ), the Venous Insufficiency Epidemiological and Economic Study (VEINES), the Aberdeen Varicose Vein Questionnaire (AVVQ), the Charing Cross Venous Ulceration Questionnaire (CCVUQ), and the Freiburg Questionnaire of Quality of Life in Venous Diseases. At the same time, none of them is universal and does not cover the entire continuum of CVD with consideration of the course of a particular disease.17,24

A systematic review has demonstrated that in most studies in chronic pelvic pain (CPP), the investigators used the SF- 36 questionnaire for the QOL assessment, and only in 22.2% of the studies did the QOL instruments meet more than half of the clinical validity criteria.25 The use of SF- 36, despite its informativeness, is limited by complex and lengthy mathematical calculations to obtain results, such as reverse conversion of the values of some scales, calculation of the summary score for each scale using certain keys, and the use of cumbersome formulas to determine the value of general indicators.26

The most popular tool for assessing QOL in patients with CVD is CIVIQ.27-30 This questionnaire, due to its specificity, is focused on assessing changes occurring in the lower extremities and is not able to reflect manifestations disturbing patients with PCS, which precludes its use in this disease. At the same time, the relevance and need for a tool for assessing QOL in this disease is beyond doubt.9,14

Currently, the clinical assessment of PCS is mainly restricted to the measurement of pain via various modified tools, which, unfortunately, do not comprehensively reflect the entire multifaceted palette of clinical manifestations of this disease.9,31

Most often, when evaluating changes in the clinical course of PCS, the visual analog scale (VAS) of pain is used as a quantitative tool for assessing symptoms.32-36 The intensity of pain as assessed by patients with PCS ranges from scores of 7.2 to 8.5.37-39 In addition, to rank the pain syndrome, the numerical rating scales, verbal rating scales, and the McGill Pain Questionnaire (MPQ) are used.32,40-42 In this case, the patient is given an evaluation sheet with a scale offering to evaluate pain sensations in numerical values from 0 (no pain) to the value defined as maximum intensity (up to 10 or 100). The results gathered from such scales strongly depend on the subjective psychosomatic characteristics of the patient, as well as on the degree of responsibility of the researcher explaining the rules for filling in these scales. A significant drawback of these scales is the emotional component of the respondent, which introduces significant biases in the indicators.43 The subjectiveness of VAS can significantly distort the objective picture of the disease, as the patient may deliberately under- or overestimate the values.

As for PCS, the use of the following severity scores has been proposed: the Venous Clinical Severity Score (VCSS), the Venous Segmental Disease Score (VSDS), and the Villalta-Prandoni scale.44 Unlike VAS, rating scales exclude the arbitrary selection of responses by the patient. The VCSS is the most commonly used tool for assessing CVD severity, and it involves 4 response options (each with scores from 0 to 3) with a defined characteristic of the pain symptom.45-48 Such a formulation of questions limits the influence of the investigator’s personality and excessive subjectivization by the patient. In addition to the pain symptom, the scale includes other clinical characteristics of CVD and consists of 10 items. The high reproducibility of responses, good validation results, its suitability for patients with all classes of CVD, and the ability to demonstrate minor changes in the patient’s condition make it an ideal tool for assessing CVD severity and determining the clinical efficacy of treatment.49 Despite its advantages, this clinical scale, due to its specificity, is focused on the assessment of changes occurring in the lower extremities and is not able to reflect the manifestations that disturb female patients with PCS.

VSDS takes into account an involvement of various segments of the venous bed of the lower extremities in the process of reflux or obstruction.18 The Villalta-Prandoni scale is focused on the dynamic assessment of the state of the lower extremities in post-thrombotic disease.50 The above factors exclude the use of these scales in female patients with PCS due to low informativeness of these methods. As for other potential tools for assessing PCS, the von Korff questionnaire, which was validated in a group of patients with chronic prostatitis, and the Endometriosis Health Profile-30 and Uterine Fibroid Symptom and Quality of Life (UFS-QOL) questionnaires, due to their specificity to the underlying disease, are not acceptable for PCS assessment.9,51-54

Therefore, the main priorities in the clinical assessment of CVD will be to evaluate the status of the lower extremities.

Pelvic Varicose Veins Questionnaire

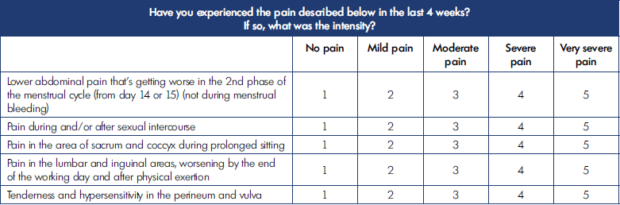

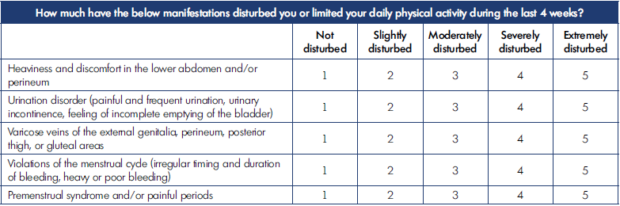

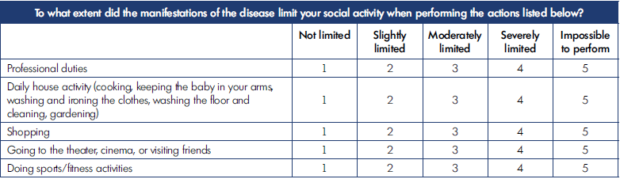

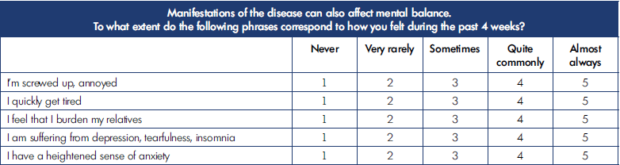

On the basis of the analysis of complaints and objective symptoms in patients with PCS, we developed an original QOL questionnaire for female patients with PCS. The prototype of the questionnaire was the well-known CIVIQ tool, which was adapted taking into account the manifestations of PCS. This tool was named by analogy with the prototype as Pelvic Varicose Veins Questionnaire (PVVQ).

PVVQ reflects psychological well-being, which are the most informative criteria for self-assessment of QOL. Each dimension includes 5 questions that maximally reveal the depth of pathological changes occurring in PCS in terms of the studied health factor.

The QOL assessment is carried out using a special form with 20 questions, each with a 5-score scale (1, normal; 2, mild; 3, moderate; 4, severe; and 5, very severe disturbances) (Tables I-IV).

The lower the summary score, the better the QOL from the patient’s perspective. The summary score for all 20 questions is interpreted as the following: 20, the highest (best) QOL; 21-40, mild impairment of QOL; 41-60, moderate impairment of QOL; 61-80, severe impairment of QOL; and 81-100, gross violation of QOL.

PVVQ was validated in line with international standards and the QOL research methodology with an assessment of the main psychometric properties (reliability, validity, and sensitivity).55 The validation study included 304 females with verified PCS and 93 controls without signs of CVD (397 females in total). The results of validation were very encouraging, which allows us to consider PVVQ an appropriate tool for assessing QOL.

The reliability of PVVQ was proven by evaluating 3 parameters: internal consistency (intra-item Cronbach’s α=0.807, inter-item α=0.919, average Spearman rank correlation coefficient rs=0.598), discriminant validity (P<1x10-30), and internal consistency (P=0.346). The analysis of construct validity versus an external tool such as SF-36 confirmed statistically significant correlations based on the convergent (-0.663≤rs≤-0.709) and divergent (-0.293≤rs≤- 0.399) validity. The sensitivity assessment demonstrated a statistical significance of the results after the treatment (P=7.75×10-8).

Pelvic Venous Clinical Severity Score

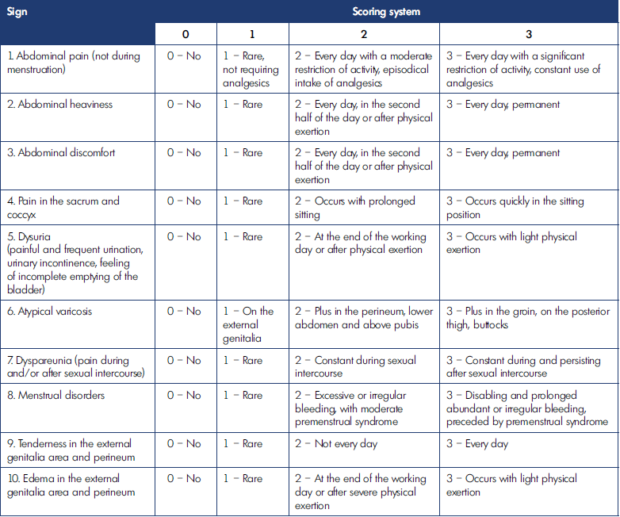

Similarly, the clinical severity scale for female patients with PCS, the Pelvic Venous Clinical Severity Score (PVCSS), was developed based on the analysis of clinical manifestations. Its prototype was the well-known venous clinical severity score (VCSS).

It does not require use of special instrumental tools when assessing PCS severity with the developed scale. The investigator takes a patient’s history, performs the clinical examination, and asks the patient to fill in a special form with a 10-score scale (Table V).

In PVCSS, each of the 10 manifestations of PCS is rated by the severity of objective and subjective signs from scores ranging from 0 to 3: 0, no symptoms; 1, episodic symptoms; 2, persistent symptoms without a decrease in QOL; and 3, severe symptoms with QOL reduction.

PVCSS provides low variability in the patient’s responses regardless of the characteristics of the personalities of both investigator and patient. In addition, the survey and examination of the patient in accordance with the scale items reminds the doctor of all the necessary studies that must be performed for a thorough examination. After filling in the form, the investigator calculates the summary score rated from 0 (no PCS signs) to 30 (most advanced disease). The global index is interpreted as follows: 1-10, mild; 11-20, moderate; and 21-30, severe disease.

The PVCSS validation was consistent with the validation principles of PVVQ and proved its validity as a tool for assessing PCS severity. The construct validity was assessed against VAS elements as external criteria. Good internal consistency was confirmed, with moderate relationships (α=0.803, rs=0.365). The validation tests demonstrated a high discriminant validity (P<1x10-30) and internal consistency (P=0.981), a high and marked strength of relationships with VAS when assessing convergent validity (0.663≤ rs≤0.813), as well as weak and moderate relationships when assessing divergent validity (0.081≤ rs≤0.349). A high sensitivity was also confirmed (P=3.65×10-7).

Evaluation of the clinical efficacy of pharmacotherapy for PCS

The history of pharmacotherapy for PCS includes the combined use of agents from different classes. Analgesics and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) reduce the level of CPP but cannot constitute the background and long-term treatment.14,56

Several limited studies of hormonal and psychotropic drugs have been performed in small samples of patients and provided contradictory results. The findings from one of two known placebo-controlled studies of the use of hormones suggested there are some treatment benefits in terms of temporary CPP relief, although at a higher rate of adverse events.57 However, the second study did not confirm the efficacy of such treatment.58 A number of studies conducted without a placebo group also could not provide unequivocal evidence of the safety and benefits of using various hormonal drugs.39,59-61 The analgesic effect of sex hormones is achieved by the suppression of ovarian function with a decrease in estrogen production and inhibition of menstruation. Adverse effects of hormonal treatment include weight gain, emotional lability, flashes, and osteoporosis. Thus, the positive effect of hormonal drugs is very doubtful, given a significant number of complications, temporary effects, and suppression of fertile function.

The available studies of psychotropic drugs with a placebo group have not demonstrated a decrease in the VAS pain score.62,63 Other studies that have proven their benefit in this category of patients are limited by a number of significant factors, such as small sample sizes, the absence of a placebo group, and reported data on the rate and severity of adverse events.64-66 In one study, all patients received additional physiotherapy and psychotherapy.67 Thus, the lack of a convincing evidence base does not allow for unconditional advisement of widespread use of psychotropic drugs in patients with PCS.

Unfortunately, almost all reviews on the pharmacological treatment of PCS include the selective vasoconstrictor ergotamine and suggest its positive effects. However, the results of 2 studies cannot substantiate a basis for its administration in patients with PCS. One of these studies reported a decrease in the diameter of pelvic veins (by 35%) and in the level of CPP for a maximum follow-up period of 4 days, and the second confirmed venous constriction within 20 minutes of its administration.68,69 The drug can provoke episodes of arrhythmias and angina pectoris, convulsions, confusion, etc. The above factors support the need to “forget” about this drug in the treatment of PCS.

Meta-analyses and systematic reviews indicate some short-term efficacy of drugs suppressing ovarian function in the reduction of CPP. However, due to inhibition of fertility and several adverse effects, along with their limited efficacy, these agents are not appropriate for the long-term treatment of CPP.70-73

The only pharmacological agents recommended by consensus documents are venoactive drugs (VADs).14,43 The largest evidence base in this group has been obtained for the micronized purified flavonoid fraction (MPFF). In the well-known placebo-controlled studies performed by one research team, MPFF use was accompanied by a significant decrease in the intensity of CPP and had no adverse effects. The use of certain vitamins, which may have a protective or damaging effect on veins, as placebo in these studies limits the validity of the results.74,75 The efficacy of medical therapy in these studies was evaluated using the CPP scales. However, as noted above, the clinical manifestations of PCS are not limited to the pain syndrome and include at least 10 other signs and symptoms.

Studies of some Russian researchers have proven the MPFF benefits in terms of reduction both in CPP and other symptoms of PCS.34,76-78

We performed a randomized placebo-controlled study of the clinical efficacy of MPFF in patients with PCS.79 The study included 83 females with PCS diagnosed by duplex ultrasound (DUS). The study group consisted of 42 patients who took MPFF at a dose of 1000 mg daily. The control group of 41 patients received placebo. The treatment duration was 2 months. As for the assessment tools, the PVVQ, PVCSS, and VAS were used.

In the MPFF group, the mean global PVVQ QOL index decreased significantly from 45.1±14.7 at baseline to 36.6±10.6 at end of treatment (mean change: 8.2±10.4), while no significant change was observed in the control group (mean change: –0.3±4.0). The between-group difference was statistically significant (P<0.001). Compared with control, significant improvements were observed in all 4 QOL parameters (pain, physical, social, psychological, all P<0.001). The mean PVCSS summary score decreased significantly by 3.4±3.4 in the MPFF group (P<0.001), whereas there was only a nonsignificant change of -0.2±1.6 in the control group (between-group difference P<0.001). In the MPFF group, improvements were statistically significant for 6 out of 10 clinical manifestations of PCS measured using the PVCSS, including pain (mean change from baseline: 0.5±0.7), heaviness (0.4±0.7), discomfort (0.6±0.7), and tenderness (0.3±0.5). No significant improvements were observed in the control group. When measured by VAS, between-group differences were statistically significant for the summary score (P<0.001) and for 8 out of 10 PCS symptoms, including leg pain (mean MPFF change from baseline: 2.0±2.2), heaviness (1.3±2.1), discomfort (1.5±2.0), tenderness (0.9±1.9), and edema (1.3±2.1). During the study, one adverse event group (dyspeptic phenomena) was registered in a patient from the MPFF group, which resolved spontaneously by the third day of taking the drug. Therefore, the largest evidence base accumulated for VADs indicate that these agents and, particularly, MPFF are safe and effective treatments for PCS due to their ability to improve QOL and reduce the disease severity, as well as each of its symptoms.

Discussion

The modern armamentarium of doctors includes both instrumental and clinical methods for the objective assessment of treatment efficacy. The ultimate goal for any treatment effect on the pathological process in the human body is the improvement in the patient’s clinical state in terms of elimination of symptoms and signs and the absence of complaints. Evaluation of treatment results based only on the laboratory or instrumental tests is always risky, as it is incomplete and does not take into account the patient’s personality. Better results from instrumental diagnostic methods are not a sufficient target. Such positive instrumental changes do not always correspond with an improvement in the patient’s state. Despite improvements with instrumental diagnostic tools, patients aren’t prone to consider treatment results satisfactory when they do not see improvement in their state. For comprehensive assessment of the quality of treatment, as well as practical evaluation of its success or failure, the investigator needs a unified tool for objectifying the patient’s clinical state, which is based on the quantitative criteria developed by standardizing the characteristics and symptoms of the disease at certain time points.19,20

The proposed tools for clinical evaluation, PVVQ and PVCSS, have been used in our clinic for a long time, creating a positive experience, and they have proven their feasibility in the evaluation of conservative and surgical methods of treatment.77,79-83

Having these tools available to an investigator enables them to evaluate efficacy of the health care provided and to receive an objective assessment of its quality by the patient, the main object of its application. Statistical and graphical analysis of the status of patients with PCS provides individual monitoring of QOL and disease severity, as described by clinically significant changes in parameters after use of various treatment methods in various groups of patients in order to select the most optimal one.

Our study demonstrates the wide possibilities of using these tools for assessment, as well as the efficacy and safety of MPFF in the treatment of patients with PCS in routine clinical practice.

The pathophysiological component of the symptomatic manifestations of PCS is a disturbance in venous hemodynamics due to blood stasis in the lower pelvis. In patients with PCS, treatment with MPFF is associated with a decrease in venous reflux, correction of hemorheology and venous tone, restoration of physiological pelvic circulation, elimination of microcirculatory disorders, relief of inflammatory reactions, improvement in lymphatic drainage function, and reduction in blood congestion in the veins of the lower pelvis with subsequent symptom relief.74-79,84-87

Therefore, from the position of evidence-based medicine, MPFF plays a very important role in the treatment of female patients with PCS, contributing to its advantages over other VADs. MPFF therapy leads to pain relief, increase in physical and social activity, and correction of the psychological state of a woman, her marital and family functions and working capacity.79,85

Despite the evidence of progress in medical treatment of PCS, there are still many issues that need to be addressed. The latest studies on the use of hormonal and psychotropic agents in PCS were carried out about 20 years ago. Since that time, many new agents and a variety of laboratory and instrumental tools have become available. Therefore, an integrated interdisciplinary approach is needed for the scientific developments in this area, with the involvement of gynecologists-endocrinologists and psychoneurologists. New large-scale studies of MPFF efficacy are warranted to address questions about the optimal dosing regimen of the drug and the possibility of its use in pregnant women. The listing of PCS as a separate nosological entity in MPFF instructions for use is advised.

Conclusion

The new patient-oriented tools of clinical assessment in PCS, namely PVVQ and PVCSS, are disease-specific, simple, accessible, and convenient clinical diagnostic methods that make it possible to carry out quantitative assessment, statistical processing, analysis, and interpretation of the data obtained. They are characterized by high reliability, validity, and sensitivity to changes.

The practical use of these tools in the evaluation of the pharmacological treatment of PCS has proven the clinical efficacy of MPFF in terms of the reduction in disease severity and an improvement in the QOL of patients.

REFERENCES

1. Rabe E, Guex JJ, Puskas A, Scuderi A, Fernandez Quesada F; VCP Coordinators. Epidemiology of chronic venous disorders in geographically diverse populations: results from the Vein Consult Program. Int Angiol. 2012;31(2):105-115.

2. Giacchetto C, Cotroneo GB, Marincolo F, Cammisuli F, Caruso G, Catizone F. Ovarian varicocele: ultrasonic and phlebographic evaluation. J Clin Ultrasound. 1990;18(7):551-555.

3. Howard FM. Chronic pelvic pain. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101(3):594-611.

4. Liddle AD, Davies AH. Pelvic congestion syndrome: chronic pelvic pain caused by ovarian and internal iliac varices. Phlebology. 2007;22(3):100-104.

5. Pyra K, Woźniak S, Drelich-Zbroja A, Wolski A, Jargiełło T. Evaluation of effectiveness of embolization in pelvic congestion syndrome with the new vascular occlusion device (ArtVentive EOS™): preliminary results. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2016;39(8):1122-1127.

6. Smith PC. The outcome of treatment for pelvic congestion syndrome. Phlebology. 2012;27(suppl 1):74-77.

7. Bell D, Kane PB, Liang S, Conway C, Tornos C. Vulvar varices: an uncommon entity in surgical pathology. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2007;26(1):99-101.

8. Butros SR, Liu R, Oliveira GR, Ganguli S, Kalva S. Venous compression syndromes: clinical features, imaging findings and management. Br J Radiol. 2013;86(1030):20130284.

9. Khilnani NM, Meissner MH, Learman LA, et al. Research priorities in pelvic venous disorders in women: recommendations from a multidisciplinary research consensus panel. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2019;30(6):781-789.

10. Lima MF, Lima IA, Heinrich-Oliveira V. Endovascular treatment of pelvic venous congestion syndrome in a patient with duplication of the inferior vena cava and unusual pelvic venous anatomy: literature review. J Vasc Bras. 2019;19:e20190017.

11. Wozniak S. Chronic pelvic pain. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2016;23(2):223-226.

12. Asciutto G, Asciutto KC, Mumme A, Geier B. Pelvic venous incompetence: reflux patterns and treatment results. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2009;38(3):381-386.

13. Eklof B, Perrin M, Delis KT, et al. Updated terminology of chronic venous disorders: the VEIN-TERM transatlantic interdisciplinary consensus document. J Vasc Surg. 2009;49(2):498-501.

14. Antignani PL, Lazarashvili Z, Monedero JL, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of pelvic congestion syndrome: UIP consensus document. Intl Angiol. 2019;38(4):265-283.

15. Meissner MH, Khilnani NM, Labropoulos N, et al. The symptoms-varicespathophysiology classification of pelvic venous disorders: a report of the American Vein & Lymphatic Society International Working Group on Pelvic Venous Disorders. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2021;9(3):568-584.

16. Almeida JI, Wakefield T, Kabnick LS, Onyeachom UN, Lal BK. Use of the clinical, etiologic, anatomic, and pathophysiologic classification and venous clinical severity score to establish a treatment plan for chronic venous disorders. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2015;3(4):456-460.

17. Gloviczki P, ed. Handbook of Venous and Lymphatic Disorders: Guidelines of the American Venous Forum. 4th ed. Front Cover. CRC Press; 2017:866.

18. Rutherford RB, Padberg FT Jr, Comerota AJ, Kistner RL, Meissner MH, Moneta GL. Venous severity scoring: an adjunct to venous outcome assessment. J Vasc Surg. 2000;31(6):1307-1312.

19. Novik A.A. Guidelines for the study of quality of life in medicine. Text in Russian. CJSC OLMA Media Group;2007:320.

20. Staquet MJ. Quality of life assessment in clinical trials. Oxford University Press; 1998:360.

21. Study protocol for the World Health Organization project to develop a Quality of Life assessment instrument (WHOQOL). Qual Life Res. 1993;2(2):153-159.

22. Fayers PM, Machin D. Quality of Life. Assessment, analysis and interpretation. John Wiley and Sons Ltd; 2000:393.

23. Carr AJ, Higginson IJ. Are quality of life measures patient centred? BMJ. 2001;322(7298):1357-1360.

24. Zenati N, Bosson JL, Blaise S, Carpentier P. Health related quality of life in chronic venous disease: systematic literature review. Article in French. J Med Vasc. 2017;42(5):290-300.

25. Neelakantan D, Omojole F, Clark TJ, Gupta JK, Khan KS. Quality of life instruments in studies of chronic pelvic pain: a systematic review. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2004;24(8):851-858.

26. Ware JE, Snow KK, Kosinski M, Gandek B. SF-36 Health Survey. Manual and interpretation guide. The Health Institute, New England Medical Center. Nimrod Press; 1993:316.

27. Launois R, Reboul-Marty J, Henry B. Construction and validation of a quality of life questionnaire in chronic lower limb venous insufficiency (CIVIQ). Qual Life Res. 1996;5(6):539-554.

28. Guillen K, Falvo N, Nakai M, et al. Endovascular stenting for chronic femoroiliac venous obstructive disease: clinical efficacy and short-term outcomes. Diagn Interv Imaging. 2020;101(1):15-23.

29. Maggioli A, Carpentier P. Efficacy of MPFF 1000 mg oral suspension on CVD C0s-C1-related symptoms and quality of life. Int Angiol. 2019;38(2):83-89.

30. Varetto G, Gibello L, Frola E, et al. Day surgery versus outpatient setting for endovenous laser ablation treatment. A prospective cohort study. Int J Surg. 2018;51:180-183.

31. Dargie E, Gilron I, Pukall CF. Selfreported neuropathic pain characteristics of women with provoked vulvar pain: a preliminary investigation. J Sex Med. 2017;14(4):577-591.

32. Brown CL, Rizer M, Alexander R, Sharpe EE 3rd, Rochon PJ. Pelvic congestion syndrome: systematic review of treatment success. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2018;35(1):35-40.

33. Daniels JP, Champaneria R, Shah L, Gupta JK, Birch J, Moss JG. Effectiveness of embolization or sclerotherapy of pelvic veins for reducing chronic pelvic pain: a systematic review. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2016;27(10):1478-1486.e8.

34. Gavrilov SG, Moskalenko YP, Karalkin AV. Effectiveness and safety of micronized purified flavonoid fraction for the treatment of concomitant varicose veins of the pelvis and lower extremities. Curr Med Res Opin. 2019;35(6):1019-1026.

35. Guirola JA, Sánchez-Ballestin M, Sierre S, et al. A randomized trial of endovascular embolization treatment in pelvic congestion syndrome: fibered platinum coils versus vascular plugs with 1-year clinical outcomes. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2018;29(1):45-53.

36. Siqueira FM, Monsignore LM, Rosa-ESilva JC, et al. Evaluation of embolization for periuterine varices involving chronic pelvic pain secondary to pelvic congestion syndrome. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2016;71(12):703-708.

37. Laborda A, Medrano J, de Blas I, Urtiaga I, Carnevale FC, de Gregorio MA. Endovascular treatment of pelvic congestion syndrome: visual analog scale (VAS) long-term follow-up clinical evaluation in 202 patients. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2013;36(4):1006-1014.

38. Lopez AJ. Female pelvic vein embolization: indications, techniques, and outcomes. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2015;38(4):806-820.

39. Soysal ME, Soysal S, Vicdan K, Ozer S. A randomized controlled trial of goserelin and medroxyprogesterone acetate in the treatment of pelvic congestion. Hum Reprod. 2001;16(5):931-939.

40. Heller GZ, Manuguerra M, Chow R. How to analyze the visual analogue scale: myths, truths and clinical relevance. Scand J Pain. 2016;13:67-75.

41. Horgas AL. Pain Assessment in Older Adults. Nurs Clin North Am. 2017;52(3):375-385.

42. Rosas S, Paço M, Lemos C, Pinho T. Comparison between the visual analog scale and the numerical rating scale in the perception of esthetics and pain. Int Orthod. 2017;15(4):543-560.

43. Morgan GE Jr, Mikhail MS, Murray MJ. Clinical Anesthesiology. 3rd ed. USA. McGraw-Hill Medical; 2005:1108.

44. Stoyko-Yu M, Kirienko AI, Zatevakhin II, et al. Diagnostics and treatment of chronic venous disease: guidelines of Russian Phlebological Association. Article in Russian. Flebologiya. 2018;3:146-240.

45. Vasquez MA, Munschauer CE. Venous clinical severity score and quality-of-life assessment tools: application to vein practice. Phlebology. 2008;23(6):259- 275.

46. Conway RG, Almeida JI, Kabnick L, Wakefield TW, Buchwald AG, Lal BK. Clinical response to combination therapy in the treatment of varicose veins. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2020;8(2):216-223.

47. Liu X, Zheng G, Ye B, et al. A retrospective cohort study comparing two treatments for active venous leg ulcers. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99(8):e19317.

48. Mohamed AH, Leung C, Wallace T, Smith G, Carradice D, Chetter I. A randomized controlled trial of endovenous Laser Ablation Versus Mechanochemical Ablation with ClariVein in the management of superficial venous incompetence (LAMA Trial). Ann Surg. 2021;273(6):e188-e195.

49. Nicolaides A, Kakkos S, Baekgaard N, et al. Management of chronic venous disorders of the lower limbs. Guidelines according to scientific evidence. Part II. Int Angiol. 2020;39(3):175-240.

50. Ning J, Ma W, Fish J, Trihn F, Lurie F. Biases of Villalta scale in classifying post-thrombotic syndrome in patients with pre-existing chronic venous disease. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2020;8(6):1025-1030.

51. Turner JA, Ciol MA, Von Korff M, Berger R. Validity and responsiveness of the national institutes of health chronic prostatitis symptom index. J Urol. 2003;169(2):580-583.

52. Von Korff M, Ormel J, Keefe FJ, Dworkin SF. Grading the severity of chronic pain. Pain. 1992;50(2):133-149.

53. Jones G, Kennedy S, Barnard A, Wong J, Jenkinson C. Development of an endometriosis quality-of-life instrument: the Endometriosis Health Profile-30. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;98(2):258-264.

54. Harding G, Coyne KS, Thompson CL, Spies JB. The responsiveness of the uterine fibroid symptom and healthrelated quality of life questionnaire (UFS-QOL). Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2008;6:99.

55. Cella DF, Tulsky DS. Measuring quality of life today: methodological aspects. Oncology (Williston Park). 1990;4(5):29-38;discussion 69.

56. Nicholson T, Basile A. Pelvic congestion syndrome, who should we treat and how? Tech Vasc Interv Radiol. 2006;9(1):19-23.

57. Farquhar CM, Rogers V, Franks S, Pearce S, Wadsworth J, Beard RW. A randomized controlled trial of medroxyprogesterone acetate and psychotherapy for the treatment of pelvic congestion. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1989;96(10):1153-1162.

58. Walton SM, Batra HK. The use of medroxyprogesterone acetate 50mg in the treatment of painful pelvic conditions: preliminary results from a multicentre trial. J Obstet Gynaecol. 1992;12(suppl 2):50- 53.

59. Reginald PW, Adams J, Franks S, Wadsworth J, Beard RW. Medroxy progesterone acetate in the treatment of pelvic pain due to venous congestion. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1989;96:(10):1148- 1152.

60. Gangar KF, Stones RW, Saunders D, et al. An alternative to hysterectomy? GnRH analogue combined with hormone replacement therapy. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1993;100:(4):360-364.

61. Shokeir T, Amr M, Abdelshaheed M. The efficacy of Implanon for the treatment of chronic pelvic pain associated with pelvic congestion: 1-year randomized controlled pilot study. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2009;280:(3):437-443.

62. Stones RW, Bradbury L, Anderson D. Randomized placebo controlled trial of lofexidine hydrochloride for chronic pelvic pain in women. Hum Reprod. 2001;16(8):1719-1721.

63. Engel CC Jr, Walker EA, Engel AL, Bullis J, Armstrong A. A randomized, double-blind crossover trial of sertraline in women with chronic pelvic pain. J Psychosom Res. 1998;44(2):203-207.

64. Beresin EV. Imipramine in the treatment of chronic pelvic pain. Psychosomatics. 1986;27:(4):294-296.

65. Walker EA, Roy-Byrne PP, Katon WJ. An open trial of nortriptyline and fluoxetine in women with chronic pelvic pain. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1991;21:(3):245-252.

66. Brown CS, Franks AS, Wan J, Ling FW. Citalopram in the treatment of women with chronic pelvic pain: an open-label trial. J Reprod Med. 2008;53:(3):191-195.

67. Sator-Katzenschlager SM, Scharbert G, Kress HG, et al. Chronic pelvic pain treated with gabapentin and amitriptyline: a randomized controlled pilot study. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2005;117(21-22):761-768.

68. Reginald PW, Beard RW, Kooner JS, et al. Intravenous dihydroergotamine to relieve pelvic congestion with pain in young women. Lancet. 1987;8555:(2):351-353.

69. Stones RW, Rae T, Rogers V, Fry R, Beard RW. Pelvic congestion in women: evaluation with transvaginal ultrasound and observation of venous pharmacology. Br J Radiol. 1990;63:(753):710-711.

70. Gloviczki P, Comerota AJ, Dalsing MC, et al. The care of patients with varicose veins and associated chronic venous diseases: clinical practice guidelines of the Society for Vascular Surgery and the American Venous Forum. J Vasc Surg. 2011;53(suppl 5):2S-48S.

71. O’Brien MT, Gillespie DL. Diagnosis and treatment of the pelvic congestion syndrome. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2015;3(1):96-106.

72. Black CM, Thorpe K, Venrbux A, et al. Research reporting standards for endovascular treatment of pelvic venous insufficiency. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2010;21(6):796-803.

73. Cheong YC, Smotra G, Williams AC. Non-surgical interventions for the management of chronic pelvic pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(3):CD008797.

74. Taskin O, Uryan I, Buhur A, et al. The effects of daflon on pelvic pain in women with Taylor syndrome. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 1996;3(suppl 4):S49.

75. Simsek M, Burak F, Taskin O. Effects of micronized purified flavonoid fraction on pelvic pain in women with laparoscopically diagnosed pelvic congestion syndrome: a randomized crossover trial. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol. 2007;34(2):96-98.

76. Tsukanov A, Levdanskiy E, Tsukanov Y. Secondary varicose small pelvic veins and their treatment with micronized purified flavonoid fraction. Int J Angiol. 2015;25:(2):121-127.

77. Akhmetzianov RV, Bredikhin RA. Clinical efficacy of Detralex in treatment of women with pelvic varicose veins. Article in Russian. Angiol Sosud Khir. 2018;24:(2):93-99.

78. Gavrilov SG, Karalkin AV, Moskalenko YP, Grishenkova AS. Efficacy of two micronized purified flavonoid fraction dosing regimens in the pelvic venous pain relief. Int Angiol. 2021;40:(3):180- 186.

79. Akhmetzianov RV, Bredikhin RA. Clinical efficacy of conservative treatment with micronized purified flavonoid fraction in female patients with pelvic congestion syndrome. Pain Ther. 2021;10(2):1567- 1578.

80. Akhmetzianov RV, Bredikhin RA, Fomina EE. Quality of life assessment in patients with pelvic varicose veins. Article in Russian. Flebologiya. 2019;13(2):133- 139.

81. Akhmetzyanov RV, Bredikhin RA, Fomina EE, Ignatyev IM. Method of determining disease severity in women with pelvic varicose veins. Article in Russian. Angiol Sosud Khir. 2019;25(3):79-87.

82. Akhmetzianov RV, Bredikhin RA, Fomina EE, Ignat’ev IM. Endovascular treatment of women with pelvic varicose veins due to post-thrombotic iliac vein lesion. Article in Russian. Angiol Sosud Khir. 2019;25(4):92-99.

83. Akhmetzianov RV, Bredikhin RA, Ignat’ev IM. Immediate and remote results of endovascular embolization of ovarian veins. Article in Russian. Angiol Sosud Khir. 2020;26(4):49-60.

84. Bush R, Comerota A, Meissner M, Raffetto JD, Hahn SR, Freeman K. Recommendations for the medical management of chronic venous disease: the role of micronized purified flavanoid fraction (MPFF). Phlebology. 2017;32(suppl 1):3-19.

85. Gavrilov SG, Turischeva OO. Conservative treatment of pelvic congestion syndrome: indications and opportunities. Curr Med Res Opin. 2017;33(6):1099-1103.

86. Sapelkin SV, Timina IE, Dudareva AS. Chronic venous diseases: valvular function and leukocyteendothelial interaction, possibilities of pharmacotherapy. Article in Russian. Angiol Sosud Khir. 2017;23(3):89-96.

87. Suchkov I, Kalinin RE, Mzhavanadze ND, Kamaev AA. Influence of MPFF on endothelial function in patients with varicose veins. Phlebol Rev. 2019;suppl 1:57.