VIII. C0s – towards consensus on the diagnostics and therapy

VIII. C0s – towards consensus on the

diagnostics and therapy

Epidemiology of C0s- what do we know about?

Eberhard Rabe (Germany)

Recent CEAP-based studies demonstrated that the prevalence of C0 and C1 patients are around 70%, whereas it is 25% for C2 and C3 patients and 5% for C4 and C5,6 patients. According to the Bonn Vein study I, age was the main effector in the risk analysis for telangiectases, varicose veins, and chronic venous insufficiency. The Vein Consult Program showed that the epidemiology of chronic venous disease was geographically diverse, but the early stages (C0s, C1) were predominate (41.6%). The main symptoms were heavy legs (72.4%), leg pain (67.7%), sensation of swelling (52.7%), and nighttime cramps (44.3%). The Bonn Vein study II was realized with the identical population and procedure as in Bonn Vein study I, with a 6.6-year follow-up period. The progression of chronic venous disease in C0 and C1 patients was 3.4% per year. Significant risk factors associated with the progression of varicose veins toward venous leg ulcers include skin changes, corona phlebectatica, a higher body mass index, and popliteal vein reflux. Corona phlebectica was found to be a predictor for the incidence of chronic venous insufficiency (relative risk [severe corona phlebectica vs no corona phlebectica], 5.23; 95% CI, 3.68, 7.43). It is important to have a general understanding of how symptoms may be expressed and interpreted, as well as how they might or might not be related to venous disease. The absence of symptoms does not exclude chronic venous disease. To conclude, C0s is frequent in the adult population worldwide. Leg symptoms deserve to be assessed and treated appropriately. Having leg symptoms is not diagnostic of a venous disease. Leg symptoms in C0s may be associated with a venous pathology (eg, deep vein reflux) that is not clinically visible or with other pathology.

The link between hemodynamics and signs as well as symptoms of the chronic venous disease

Andrew Nicolaides (Cyprus)

The aim of this review was to provide a clear understanding of the pathophysiological mechanisms of chronic venous disease at different clinical stages and the possible role of these mechanisms in the development of symptoms in C0s clinical class of the CEAP classification, which consists of symptomatic patients without any visible or palpable signs of venous disease. The prevalence of C0s varies between 13% and 23% of the general population according to several epidemiological studies. Wall remodeling and valve destruction due to white cell endothelial interaction is the main cause of primary varicose veins, while deep vein thrombosis produces secondary changes leading to the postthrombotic syndrome. The underlying mechanism of skin changes and ulceration is venous hypertension, which is transmitted to the skin microcirculation. Over the last 10 years, an improved video capillaroscopic technique, the orthogonal polarization spectral imaging technique demonstrated that quantitative measurements in the skin microcirculation are progressively altered from C1 to C6 patients and that certain values in chronic venous disease patients are significantly different from healthy subjects (P<0.05): (i) capillary diameter increases and capillary morphology worsens from C2 to C5; (ii) the diameter of the dermal papilla and the capillary bulk increase from C3 to C5; and (iii) functional capillary density decreases from C4 to C5. In addition, significant changes have been shown between C0a and C0s patients despite the presence of normal conventional duplex scans in the latter, including a decrease in functional capillary density and an increase in the diameter of the dermal papilla.

Functional abnormalities found in C0s patients in recent studies include increased compliance of the venous wall (hypotonic phlebopathy), dilatation of the deep veins in the calf producing an abnormally increased venous volume, reduction in emptying of the venous reservoir, reduction in the venoarteriolar response on standing and blood reflux in small venules despite a normal conventional duplex scan. However, most of the studies are small and their findings need to be confirmed with a larger series. It remains to be seen whether functional changes and microcirculatory changes respond to venoactive medications in parallel to the relief of symptoms.

Symptoms of the chronic venous disease learning through a clinical case. How to assess the symptoms of the chronic venous disease – 2019 update?

Nicos Labropoulos (US)

The SymVein consensus report was produced to describe the venous symptoms, to specify which components enable symptoms to be attributed to a venous cause, to determine their pathology, to establish a score dedicated to symptoms, to determine which clinical examination and investigations are useful for identifying the venous cause of symptoms and to explain the lack of correlation between the persistence of symptoms and a successful procedure. By definition, venous symptoms are related to venous etiology, but, as venous symptoms are rarely specific, this makes their definition difficult. In order to solve this challenge, some points needs to be clarified, such as “Are venous symptoms of primary etiology caused by an alteration in the major veins or by venule and capillary anomalies?,” “Would major vein alterations be related to reflux in superficial and/or deep veins or to compression of proximal veins?,” “Could small venules or capillaries be involved in C0s patients, knowing that both anomalies (major veins and venules) may be combined in C6 patients?,” “Should the absence of clinical venous signs and the absence of reflux on duplex scanning or air plethysmography systematically rule out a venous etiology?,” and “ Is the presence or the intensity of symptoms, independently of the presence of signs, predictive of chronic venous disease progression?.”

The presence and severity of symptoms are subjective. In the Vein Consult Program, more than 80% of the patients presented with symptomatic chronic venous disease. In the Bonn Vein study, more than 50% of the 1800 patients reported chronic venous disease–related symptoms. Limb symptoms are by themselves not diagnostic of venous disease and they deserve to be assessed and treated appropriately. Symptoms are unique and personal experiences. These feelings are variously expressed and with differing intensities, and they may mean many different things to different patients. The story and the clinical context of symptoms are important when conducting an assessment. Distribution and extent of reflux, amount of reflux, distribution and extent of venous obstruction, severity of obstruction, muscle pump efficiency, genetic predisposition, soft tissue cellular responses, rate of chronic venous disease progression, obesity, hormonal factors, and right heart failure are factors contributing in the clinical severity of chronic venous disease.

Chronic venous disease progression- is it unavoidable?

Marc Vuylsteke (Belgium)

Varicose veins are present in 23% of the adult population and chronic venous insufficiency is present in 11% to 17% of the adult population. For chronic venous disease, the progression rate to higher clinical stages reaches 4% per year. Half of the patients with unilateral varicosities develop contralateral chronic venous disease in several years. One-third of patients with varicose veins (C2) will develop skin changes in 13 years. Untreated patients will develop more signs and symptoms, which has an impact on health-related quality of life for the patients. Persistent venous hypertension, consequences of chronic inflammation within the venous wall and genetics may be independent factors influencing the progression of chronic venous disease. The treatment options are lifestyle changes (weight loss, exercise), compression/leg elevation, medication, and interventional treatments. Risk factors for venous disease include a positive family history of chronic venous disease, pregnancy, obesity, standing/sitting habit, smoking, lack of regular exercise, female sex, and age. Among these risk factors, age, sex, and family history are immutable; however, weight, physical activity, smoking can be modified. The CEAP clinical stage of venous disease is more advanced in obese patients than in nonobese patients, which is a result of increased intra-abdominal pressure. Obesity correlates with symptoms of chronic venous insufficiency, but two-thirds of limbs have no anatomic evidence of venous disease.

Compression improves venous pump function and enhances venous flow velocities. At various stages of chronic venous disease, compression significantly reduces edema, improves symptoms, and has a positive effect on a patient’s quality of life. There is insufficient information from randomized controlled trials on preventing chronic venous disease progression with compression; however, the incidence of chronic venous disease progression is higher among patients who are noncompliant with compression stockings. Anti-inflammatory treatment options, such as micronized purified flavonoid fraction (MPFF), reduces the expression of adhesion molecules, reduces the adhesion of leukocytes to the endothelium, decreases capillary permeability, and improves venous tone, suggesting a reduction in the progression of chronic venous disease. In one study, 96 C1s patients were treated with MPFF 1000 mg/daily for 3 months, and 55% of the patients had transient reflux in the great saphenous vein (segmental) on duplex ultrasound. The results showed that the symptoms (leg heaviness, fatigue, pain, nighttime cramps) ceased in 88% of patients and the transient reflux was eliminated in 92% of patients at 3 months with MPFF treatment. There is a need for more randomized, double-blind, controlled clinical trials with long follow-up periods. Sclerotherapy (foam), surgery, endovenous techniques, and other interventional techniques provide clinically significant improvements to patients’ quality of life. The recurrence rates for varicose veins are very high: 40% to 50% at 5 years and 70% at 10 years. Of the surgical procedures, 20% are carried out to treat recurrent disease.

In conclusion, several treatment options can be used for treating chronic venous disease, including venoactive drugs. Risk factors have to be assessed carefully. Progression of disease in most patients is not preventable, as the causes of varicose recurrence are multifactorial and only some of them can be prevented.

C0s diagnostics-objective evaluation and possibilities of confirmation of the chronic disease presence in C0s patients

Patrik Carpentier (France)

C0s does not have a clear prognostic value regarding the subsequent occurrence of varicose veins or venous insufficiency. Although venous symptoms are essentially subjective, they can be objectively evaluated using patient-reported outcome measures: visual analog scale and quality of life scales. C0s symptoms are probably related to subclinical leg edema. Ankle edema measurements can probably be used to assess the pathophysiological substratum of C0s symptoms. Water displacement volumetry, optoelectronic methods, bioimpedance spectroscopy, dermal ultrasonography are some methods to evaluate edema. However, there is a need for future studies to validate new methods of edema assessment using innovative technologies. As C0s symptoms can be found in subjects with any cause of calf muscle pump dysfunction (venous or nonvenous), evaluation of the calf muscle pump is certainly what is most needed in order to further understand this pathology. Ultrasound duplex venous evaluation of C0s patients is recommended. Nevertheless, the potential of high-resolution ultrasound and capillaroscopy for the detection of early chronic venous disease in some C0s patients remains to be determined.

C0s treatment possibilities-2019 update

Stavros Kakkos (Greece)

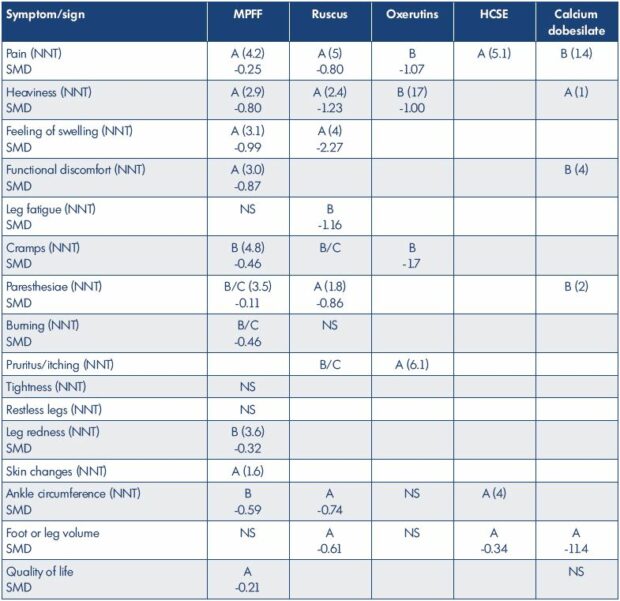

Venoactive drugs, such as micronized purified flavonoid fraction, Ruscus extracts, hydroxyethylrutosides, horse chestnut seed extract, and calcium dobesilate, are widely used as important components of the treatment of chronic venous disease. They constitute a group of heterogeneous agents with different pharmacological properties, including an increase in venous and lymphatic vessel tone, anti-inflammatory actions with inhibition of leukocyte activation, trapping, and migration, leading to a protective effect against leakage of macromolecules and venous edema. Venoactive drugs can be administered alone or when compression is contraindicated (eg, in patients with peripheral vascular occlusive disease) or not tolerated because of patient pruritus or high ambient temperatures. Alternatively, venoactive drugs may be prescribed in combination with elastic compression, since the original trials evaluating venoactive drugs allowed use of compression, which is justified since elastic compression cannot always fully control patient symptoms. Venoactive drugs are effective in improving patient symptoms including pain, heaviness, sensation of edema, cramps, paresthesia, heat or burning sensation and other venous symptoms, but also global symptoms, and objectively assessed leg edema of chronic venous disease. Venoactive drugs are effective across the entire spectrum of chronic venous disease severity, CEAP clinical classes C0s through C6. This effectiveness has been evaluated in the original randomized control trials and subsequent observational studies. More recently, systematic reviews, including Cochrane reviews, have confirmed and quantified the favorable effects of the various venoactive drugs on chronic venous disease symptoms and signs. The relative effectiveness of venoactive drugs in chronic venous disease was assessed in the 2018 update of the international guidelines on chronic venous disease (Table 1).